For most of my adult life, clever, well-read, feminist women have told me how much they love Jilly Cooper. It therefore came as a bit of shock when I finally tried her novels for myself and found what they contained. There is, for example, no mistaking Jilly’s scorn for women who are fat and/or hairy, her belief that all female unhappiness can be cured by a damn good rogering, and the idea that not only is it fair enough for middle-aged blokes to lech after teenage girls, but that teenage girls rather like it when they do. (I was also slightly disconcerted by her favourite word for female genitalia – which, by way of a big clue, is the surname of the 41st and 43rd US presidents.)

What the show seems to know most of all is how much we secretly dislike our current pieties

So how on earth would Rivals go about adapting her work in 2024? The unexpected answer, judging from the two episodes I’ve seen so far, is pretty wholeheartedly. Now and again, you can detect a knowing glint in the show’s eye about the couldn’t-happen-now antics of the 1980s – but what that glint seems to know most of all is how much we secretly dislike our current pieties.

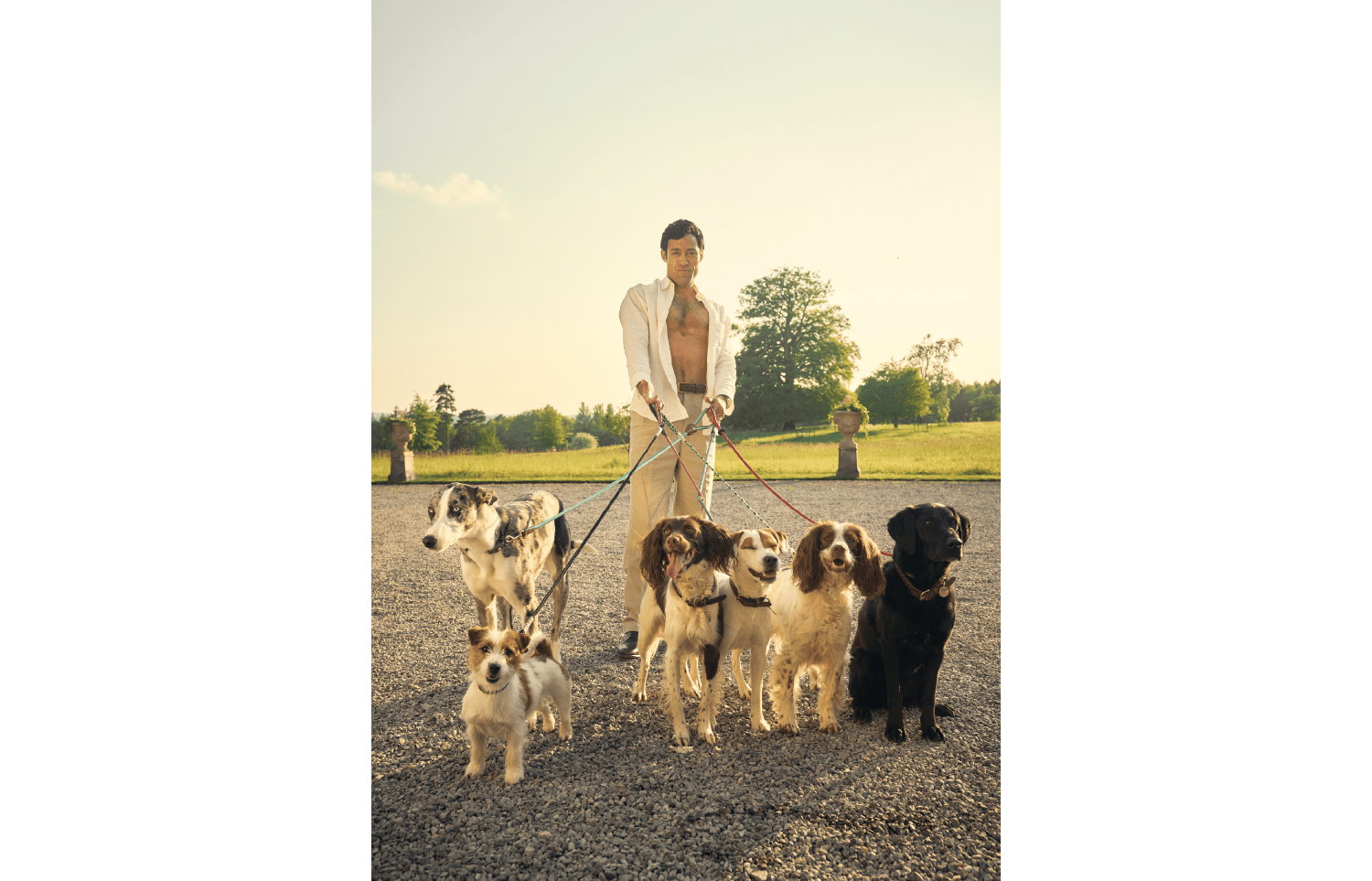

So it was that the first episode began with a kind of defiant overture. In an aeroplane toilet (Concorde naturally), vigorous sexual congress was under way, featuring the toned, thrusting bottom of Jilly’s long-standing cad Rupert Campbell-Black, a red stiletto shoe pushed hard against a wall and a climax duly accompanied by the popping of an onboard champagne bottle. Emerging afterwards, Rupert (Alex Hassell) walked down the aisle in slow motion while glossy women peered over glossy magazines, objectifying away.

And with that, it was time to introduce the show’s eponymous rivalry. Back in his seat, Rupert exchanged brittle, charged banter with Lord Tony Baddingham (David Tennant) who owns a TV channel, inevitably – if also somewhat improbably – based in the Cotswolds, where both men live and to where the action now shifted.

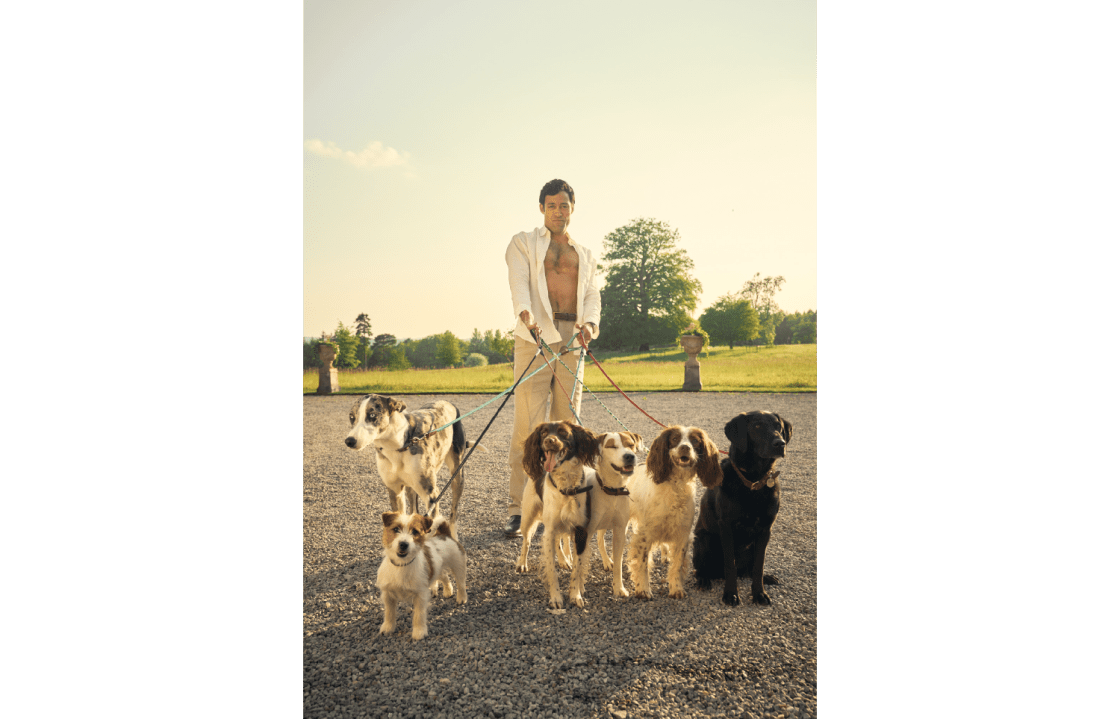

Among the other occupants of huge houses there is Tony’s new star presenter Declan O’Hara (Aidan Turner), whose wife Maud and 20-year-old daughter Taggie would soon catch Rupert’s impressively roving eye. As would Tony’s glamorous new star producer. For now, though, poor Rupert had to make do with the journalist he’d enjoyed on Concorde and the wife of an MP.

Not that he’s the only Cotswolds-dweller in possession of a pair of heaving buttocks. As a handy recap, the episode ended with multiple orgasms – which is to say multiple people, in various couplings, having one orgasm each.

Even so, the main driving force of the plot is not so much sex as class, where again at Jilly’s prompting the show takes an unfashionable line: much preferring posh people and generally regarding those who aren’t as arriviste oiks.

Leading team oik is Valerie Jones, a woman so hilariously common that she owns a boutique in Colchester and calls her drawing room ‘the lounge’. But even Lord Tony is not exempt from a sneer or two. Sadly, you see, despite his title and wealth, he’s a grammar-school boy and as a result chippy, insecure and essentially charmless. Above all, he’s eaten away with such resentment of Harrow-educated Rupert’s obvious superiority that he doesn’t realise that when Rupert gropes young Taggie, it’s just a spot of harmless upper-class fun.

Given the level of advance publicity – and the programme’s own ultimately irresistible shamelessness – Rivals seems bound to be a hit, even a well-deserved one. But however much you like it, please don’t pretend it’s remotely feminist.

And so to another series about rich people, where the younger characters are constantly shocked by the older ones’ immorality and class plays a big part. But that’s where all similarities end between Rivals and Industry – a show from the other end of the dramatic spectrum: savage rather than jolly, thoroughly researched rather than cheerfully fantastical and resolutely free of froth.

In fact, though, what makes Industry one of the best dramas on television is that its darkness and cynicism are so alarmingly convincing. Created by two former City boys and set in a London investment bank, the show is now in its third series. Yet it’s still finding ways to both horrify and titillate us with revelations as to how the world of high finance works (with staggering ruthlessness on the whole).

By now, it’s something of a cliché to compare Industry with Succession – the trouble being that it’s hard not to. After all, the two share the same sense of anger bordering on fury, combined with the same ability to channel it into perfectly controlled episodes bursting with thrilling incident, razor-sharp characterisation and high-tar acting. They also have the same sort of blistering dialogue that, in theory, should be somewhat over-theatrical in its endless fluency but that, in practice, delivers one gut-punch after another.

Comments