Mothers of America

let your kids go to the movies!

get them out of the house so they won’t know what you’re up to

it’s true that fresh air is good for the body

but what about the soul

that grows in darkness, embossed by silvery

images…

So wrote Frank O’Hara in ‘Ave Maria’, in 1964.

Matthew Specktor is the son of the talent agent Fred Specktor and the writer Katherine McGaffey, whose crushing misadventures in screenwriting seem to him a detour in what could have been a far happier life. His father’s specialism was originally ‘oddballs and misfits’, carting around actors like Jack Nicholson and Bruce Dern to no-hope castings where even Nicholson’s wolfish smile seemed wrong. But film-making was changing fast, away from conventional matinée idols into its golden age of humanist complexity on screen: men and women whose unusual faces, films and personal myths still fascinate us today.

As a teenager in the shabby Santa Monica of the late 1970s, Specktor stays out all night watching Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. When he rolls in with the dawn, his mother asks if he’s revised for his test, but also joins in with quoting the script back at him on her way to wrestle with the typewriter at the bottom of the garden. There is no chance of him not being allowed to go to the movies; but will he be able to escape them too? When he has a summer job in the mailroom at Creative Artists Agency (CAA), there’s advice from Dustin Hoffman, who’s using a spare office and with whom he shares cigarette breaks. Along with the smoking, Hoffman quips that working at this powerhouse will also be ‘bad for your health’. Specktor writes:

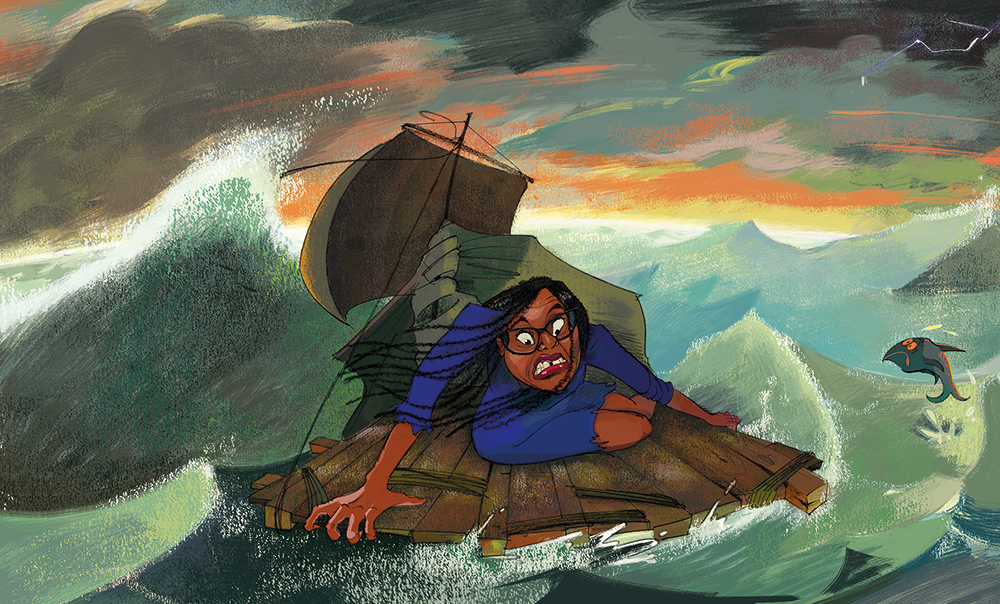

Is it? This is what I will never understand. Are the movies bad for me – so much dreaming – or are they life itself? I’ll spend the rest of my life brushing up against those people who haunt other people, crowding the margins of their dreams… I’ll never know what it means to have the movies at my mercy, to be Hollywood’s biggest star, but I’ll also never know what it’s like to be without them, now that they have colonised my imagination like a swarm of bees.

In a book that is part Hollywood history, part nuanced family memoir, the faultlines in his parents’ marriage are visible from the start. In 1963, even California is stifling. Sex is furtive and marriage proposals are made on the flimsiest grounds. Fred is a young assistant, the bullying of his working-class father having been replaced by the ‘scary’ Lew Wasserman, who makes being a marine feel like a gentle memory. The intellectual, beautiful woman with whom he falls in love is working, inevitably, as someone’s secretary, with great literature falling out of her handbag.

He will wonder that she is a person of enormous potential, someone who wouldn’t necessarily have to waste her life in the movie business. For him, this industry is an escape. For her, it could be slumming.

She carries around a copy of Ulysses. ‘Who are you going to impress?’ asks Fred. ‘Most people here don’t know James Joyce from the guy who wrote From Here to Eternity.’ What a line. For the deal-maker, Los Angeles makes life shinier. For the complicated artist, it’s an identity crisis waiting to happen. But without their uneasy love story their son wouldn’t be here to tell it.

Specktor has written authoritatively about the film industry in both fiction and criticism, but this is the first time he’s created a history that’s confessional as well as deeply researched. The combination, along with his gift for setting a scene, makes this his best book yet. While we can imagine the strangeness of being a star, The Golden Hour explores the strangeness of being ordinary in this extraordinary world, ‘impatient with a life that is merely human-sized’. As a son, as an artist himself and as a former development executive seeing the way literature is used up like so much coal, Specktor knows the film industry to be relentlessly careless of a writer’s dreams. (F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood was one of the casualties perceptively explored in Specktor’s book of essays Always Crashing in the Same Car.) In his family’s tragedy, McGaffey, who died in 2009, didn’t get enough of her second act either. His grief is as much for the life she might have had, and for all of the books she might have written, as for her loss.

Fred is now 92 and, extraordinarily, is still working at CAA as their longest standing agent, whose clients include Helen Mirren, Danny Devito, Jeremy Irons and Glenn Close. After years of pursuing Morgan Freeman, he celebrated eventually signing him with a homage ear piercing, aged 73, and remains in what his son terms his ‘eternal present’, like a basketball player who has never left the court.

In this bizarre world the boundaries between life and art might seem extremely porous, but film has always been able to get under the skin and into the soul. It remains an intoxicating form, still able to inspire hysteria from politicians who have always appreciated its power. The lights remain hopefully on, even if the golden hour is probably past.

Comments