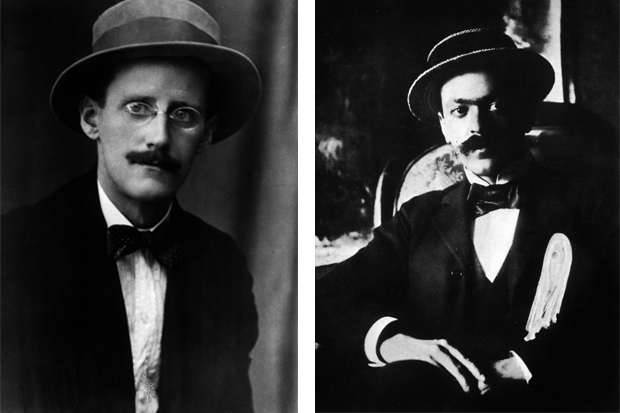

This lovely, modest and precise book tells the story of the most productive friendship among the modernists, and the most surprising. Stanley Price calls James Joyce and Italo Svevo two of the four great modernists, along with Kafka and Proust. That may overstate the case for Svevo, but no reader will reach the delightful, happy ending of their friendship and begrudge a biographer’s warm enthusiasm. Few encounters between a paint manufacturer and a teacher of English as a foreign language have ever ended in a mood so like a fairy tale.

In 1904, Joyce arrived in Trieste with a woman he had met only four months earlier called Nora Barnacle. It was not a carefully considered destination. Joyce had run away from Ireland to Paris, where he hoped to earn some money teaching English at a Berlitz school. There was no vacancy, but he was told that there was one in Zurich. No job transpired there either; but the Vienna head office assured Joyce that one was available in Trieste, then the third city of the Austro-Hungarian empire and its only port.

Off went Joyce and Nora again, and carried out what was now a well-established routine: Nora sat on a park bench with the suitcases while Joyce hunted for accommodation. On this occasion her wait was a long one, since Joyce was arrested after an argument in a bar involving several drunken English sailors and Triestine prostitutes.

More bad news was to follow; the job was not in Trieste but in Pola, 150 miles south. Nevertheless, Joyce and Nora decided to stay, and Trieste would become their home for ten years — a place, Umberto Saba wrote, where ‘one asks oneself “What am I here for? Where am I going?”’

These questions were uppermost in the mind of a prosperous Jewish-Italian businessman of Trieste, Ettore Schmitz. His family’s business, Veneziani, made naval paint, designed to repel barnacles, curiously enough. It had already become immensely successful internationally (and would be used during the first world war by five out of six engaged navies). The success had required Schmitz to travel to England, where he lived near the Veneziani factory in Charlton, south-east London, learned not to gesticulate with his hands when negotiating with the First Sea Lords, and became a passionate supporter of Charlton Athletic.

He loved England and smoking more or less equally. (What torture it must have been for him, as reported here, to go to see Carmen, that opera set around a cigarette factory.) He was the comfortable bourgeois with the knack for the biting and irreverent bon mot. When, on military service in 1885, a pompous Austro-Hungarian nobleman had reproached him for crawling up a hill too close behind him with the words, ‘Don’t come too close or you’ll bite my bum,’ Schmitz had answered: ‘Jews don’t eat pork, you know.’

Back in Trieste, Schmitz decided he needed some personal tuition in English, and the Berlitz school introduced him to a young Irishman, James Joyce. Shyly, in the course of their thrice-weekly lessons in the Schmitz apartment in the grand villa near the paint factory, Ettore confessed his secret. In the 1890s, he had published two novels under the pseudonym ‘Italo Svevo’. Joyce, too, wanted to write; in the years that followed, the pupil would be asked to read and respond to unpublished stories, ultimately intended for the collection Dubliners, and passages of experimental writing emerging for a novel called Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Svevo and Joyce got on like a house on fire — indeed a house made of straw, with a cellar used to store petrol. But as Price explains, with a fine novelistic sense of social distinctions, their friendship was an unlikely one. Nora would never have been asked to meet Svevo’s wife Livia, though she once did her washing to earn some money. The Joyces’ successive apartments, shared with Joyce’s brother and sister and their spouses, as well as the children, remained out of bounds.

Their connection was writing. Svevo was a committed, hard-working writer, despite the years of total neglect; his invocation of the importance of writing every day is still a noble one:

You have to try and bring to the surface, every day, from the depths of your being, a sound, an accent, the fossil or vegetable remains of something that may or may not exactly be thought.

His commitment, as well as his frequent gifts of money, drove Joyce onwards.

They were very different writers — Svevo dedicated to clarity and precision, Joyce with a weakness for rampant verbiage — and their differences emerged in a disagreement over the early fascist writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. Joyce maintained that he was grandly evocative; Svevo that he could open any page of d’Annunzio and find a sentence that meant absolutely nothing. Svevo won, with the sentence: ‘Il sorriso che pullulava inestinguibile, spandendosi fra I pallidi meandri dei merletti burandesi’ (‘The smile which pullulated inextinguishably, spreading among the pallid meanders of Burano lace’).

They were, nevertheless, good for one another, and each inspired a masterpiece in the other. Svevo not only affected the style of Ulysses, which Joyce was writing from 1914, but surely is hugely present in Leopold Bloom himself. And after the years with Joyce, Svevo went back and wrote the funniest great book of modernism, The Confessions of Zeno, largely about the immense pleasures of indefinitely giving up smoking.

Joyce and his family had to leave Trieste shortly after the outbreak of war, settling in Zurich, where most of Ulysses was written. ‘I met more kindness in Trieste than I ever met anywhere else,’ said Joyce touchingly, and after the war he and Nora briefly returned; but life had changed too much. They decamped to Paris, now with an entourage of admirers and patrons and the complete manuscript of a great novel.

Svevo brought his own novel to a conclusion, and published it in 1923 to a few grudging reviews in the local press. But Joyce remembered Svevo’s kindness, and was always receptive to real genius. He pressed Confessions on the most influential figures on the French literary scene, who happily agreed on the novel’s excellence, and brought it out to immense acclaim and some satisfying controversy. (The TLS wonderfully said that it was a disgrace that a novel should emerge from Italy with so little support for the country’s great new leader, Mussolini.)

Joyce humbly wrote to request permission to name the great female figure in his new work, Finnegans Wake, after Svevo’s wife. Anna Livia Plurabelle has Livia Schmitz’s name as well as her beautiful hair.

Svevo was killed in a car accident in 1928, at the point when he was enjoying the full flood of his international celebrity. He had written in the Confessions:

I am sure a cigarette has a more poignant flavour when it is the last… The last has an aroma all its own, bestowed by a sense of victory over itself and the sure hope of health and strength in the immediate future.

His last words, on being refused a cigarette, were: ‘That would have been my last.’ On being asked if he wanted to pray, he had replied: ‘When you haven’t prayed all your life, there’s no point doing it now.’

This is an enchanting book, as evocative as Svevo’s own writing, full of a novelist’s skill in evoking character and entirely convincing in its reading of events. It records one of the happiest episodes in literary history: a friendship between unlikely allies in which both abundantly kept their word.

Success for both Joyce and Svevo was hard won, and emerges like a rabbit out of a hat. In the end, it was a success that only George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf, fascists, the psychiatric profession, the inhabitants of Dublin, puritanical printers, the Berlitz school — oh, very satisfyingly, all sorts of people — could begrudge, and noisily did. What could be more agreeable than that?

Comments