I first came across the extraordinary creations of the artist and illustrator William Heath Robinson at least 60 years ago. I loved them, even though I may not have understood every nuance. When I look once more at old favourites such as the machine for conveying peas to the mouth I often spot in the corner some little twist or joke that I had not seen before.

What also wasn’t clear at the time is how prescient some of his contraptions were — in one illustration you can see a prototype selfie stick; in another he invents the silent disco. Many of his madcap solutions were semi-serious responses to societal problems. Some weren’t far off what serious inventors were coming up with themselves.

The expression ‘Heath Robinson’ has entered the dictionary to mean ‘an over-ingenious, ridiculously complicated or elaborate mechanical contrivance’. But early domestic gadgets were often ridiculously complicated. Hubert Cecil Booth’s original vacuum cleaner of 1901 was a steam-powered machine the size of a large cart, and pulled by horses. When you summoned it, the monster was brought to the road outside your house, and pipes led in through the windows. This was an important social event — ladies would invite their friends to come and take tea and observe the wonderful machine in action.

Robinson, however, went even further. There was the improbable hydraulic device for clearing the breakfast table, the auto-shampoo chair, the complex mechanical slimming engine to pummel you into shape…

William Heath Robinson was born on 31 May 1872 in Hornsey Rise, north London. His father, Thomas Robinson, earned his living by drawing illustrations for the Penny Illustrated Paper. The children loved watching — and copying — their father. Heath claimed that at an early age he ‘could draw a passable Zulu, with feathered headdress, long oval shield, and assegai’. When he was 15, Heath went to art school in Islington, where he and his fellow students ‘worked hard intermittently and talked a lot about art’. He later acknowledged the influence on his work of many predecessors and contemporaries, including Aubrey Beardsley, Kate Greenaway and various Japanese artists.

On leaving art school, Robinson tried the romantic life of a landscape painter, but things did not work out — a dealer advised him to try another profession. He made a collection of drawings instead and tramped round all the publishers in central London, eventually succeeding in selling a few.

By the time he was 24, Robinson was earning a living from his art. But it was his strip for the Daily News where the classic Heath Robinson image crystallised itself. It provoked much interest from a variety of industrial companies, who invited him to see the factories and draw what he found. These led to invitations, to see the manufacture of Swiss rolls, toffee, paper, marmalade, asbestos, beef essence and lager. A series of illustrations of ‘Great British Industries’ included such fantastical scenes as ‘Stiltonizing Cheese in the Stockyards of Cheddar’ and ‘The Pea-splitting Shed of a Soup Factory’.

In 1914 H.G. Wells sent him a letter:

It may amuse you to know that you are adored in this house. I have been ill all this Christmas-time and frightfully bored and the one thing I have wanted is a big album of your absurd beautiful drawings to turn over. Now my wife has just raided the Sketch office for back numbers with you in it and I am running over lots of you. You give me a peculiar pleasure of the mind like nothing else in the world… I hope you will go on drawing for endless years.

The peak of Robinson’s career came in the 1920s and 1930s when his fame spread worldwide and he received ever more eye-catching commissions from German paper makers and tyre manufacturers and Canadian dairy companies… In 1930, when the Pacific Steamship Company was building the luxury liner RMS Empress of Britain, they engaged Robinson to decorate its Knickerbocker Bar and Children’s Room. In 1934 the Daily Mail asked him to design a ‘Gadget House’ for its Ideal Home exhibition. A firm was paid to build it to two thirds scale, like a giant doll’s house with the front removed to reveal the inner workings.

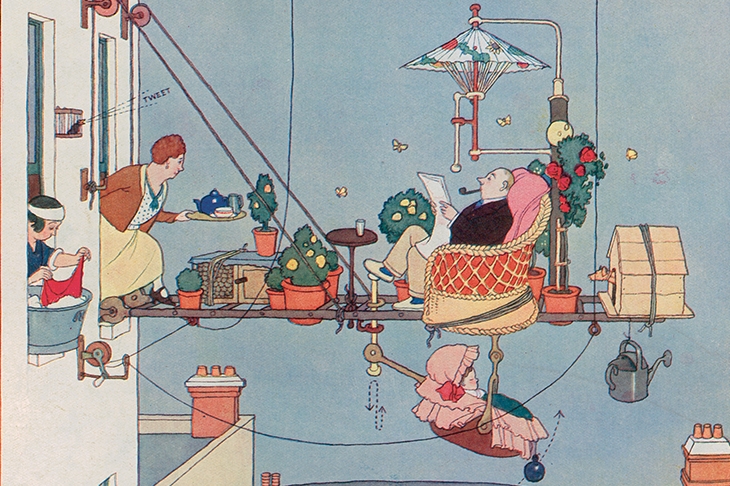

Robinson found ingenious solutions to many of the problems brought about by the rising population and aspiring middle-class families not having enough money to employ help. Servants could be replaced by pieces of string, so that people could bring themselves whatever they wanted without moving from their chairs — the early 20th-century version of remote control.

He also never forgot his experience of flat living. ‘Since the primary purpose of flats is to enable at least five families to live where only one hung out before, thereby quintupling the landlord’s income, they are apt to lack… spaciousness. From the keen cat-swinger’s point of view this is regrettable,’ he wrote in his 1936 book How To Live in a Flat.

One way of maximising the limited space available to flat dwellers was to use the balcony or, in the absence of a real balcony, a virtual one. All you needed, according to Robinson, was a few cantilevers and some pieces of rope, and you could enjoy the great outdoors. Robinson imagined greenhouses, indeed entire gardens perched in the sky. In these proposals the long arm of health and safety does not seem to have impeded him in any way.

For almost all the drawings, Robinson used just pen and ink, often with half-tones, which were sometimes printed in sepia. When he was commissioned to do pictures in colour he charged extra.

He maintained a prodigious output until his health began to fail in the summer of 1944. He died of heart failure on 13 September that year. Many artists of his era are long forgotten, but Heath Robinson’s name lives on. He has influenced a wide range of people, from Nick Park, the creator of Wallace and Gromit, to Michael Rosen and J. K. Rowling, who contemplated devising a Heath Robinson-type machine while dreaming up the Sorting Hat at Hogwarts. A Heath Robinson revival is afoot, with the formation of the William Heath Robinson Trust and the opening of the Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner, north-west London.

The secret of his enduring popularity lies in his unique ability to inject humour and humanity into the cold efficiency of the machine age. He let the outlines of his superb draughtsmanship go wonky so that his drawings share the endearingly amateur appearance of the makeshift contraptions they depict. We are invited into a reassuring world of gentle eccentricity, cheerful stoicism, a flair for improvisation and a gleeful debunking of officialdom — and anyone who takes themselves too seriously.

Comments