‘Very, very, very sexy’, a field-researcher scratches in his Antarctic notebook. He is describing a meteorite the size of a £1 coin that he has just picked up off the ice. The episode, recounted in Gabrielle Walker’s hugely informative book, reveals the passion of intrepid polar scientists. From the enthusiasm and diligence on display in these pages, one senses that the author shares their feelings.

With a PhD in natural sciences and a solid career in science journalism, Walker is well placed to tackle the wide range of polar disciplines. She calls the Antarctic a ‘science playground’, and has visited five times, kneeling over holes in the ice with many of the world’s leading researchers.

The book is structured geographically. On the east coast a biologist considers whether a penguin has a sense of self, while in the Dry Valleys (‘Mars on earth’), a geologist explains why tectonic forces that cause the rest of the world to buckle and warp have been subdued for an extraordinary stretch of time in that ‘paralysed’ landscape. At the South Pole, an astronomer sets up a telescope which will pick up the afterglow of the Big Bang. Walker uses direct speech to render the material digestible, allowing her protagonists to speak for themselves. She has a gift for lay analogy, as a popular science writer must. ‘The earliest days of the Solar System’, she writes, ‘were like a celestial billiards game with half-formed planetoids slamming into each other.’

Besides theory, Walker reveals the reality of daily life for researchers and their assistants, both on base and in the field. ‘Sharing a pyramid tent with one other person,’ she says, having done so many times, ‘you’ll cook together over a Primus stove wedged between your two sleeping areas, bathed in a cheerful orange glow as the 24-hour daylight filters through the canvas.’

Visitors to the polar regions will find useful tips here, and even in higher latitudes mature Spectator readers might take note. ‘In the endless thermo-dynamic battle to keep warm in a cold place,’ writes Walker, ‘it’s always best to use a pee bottle during the night if you can. Any pee in your bladder costs you energy to keep it at body temperature.’ And of course, there are tragedies. A leopard seal eats a diver’s head; three parachutists smash themselves to pieces near 90 degrees south; a Norwegian freezes solid as wood in the grip of a crevasse.

Walker’s attempts to illuminate non-scientific aspects of the Great White South are less successful. Philosophical speculation on the awful immensity of the continent or its symbolism fall flat, as does the self-revelation (‘I felt cradled’).

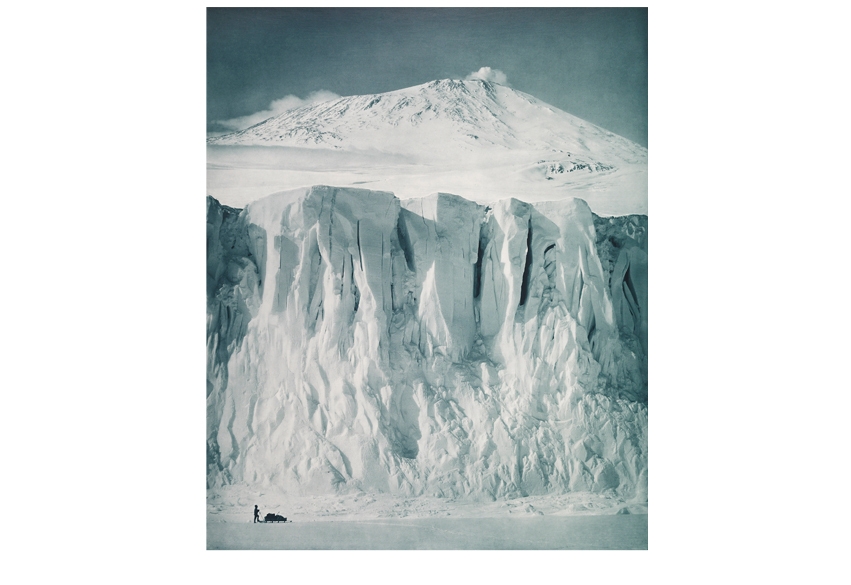

That said, she has researched the material already published and made good use of it. ‘For the people who go there’, she writes in the introduction, ‘Antarctica is a carte blanche.’ She might have said a terra incognita. As for exploration: Walker recapitulates the most familiar stories, and does so with verve — though it is not true that on Scott’s last expedition, Cherry-Garrard took the dogs out for one last search ‘merrily’. He was paralysed with anxiety, as his journal reveals.

Science writers are not required to be literary, but Walker could have reined in the cliché and flabby colloquialisms. Views are ‘to die for’, geologists are ‘worth their salt’ and the ice ‘plays ball’. One situation ‘is as cushy as it gets’. In addition, the book lacks a narrative arc, and many links creak.

(Neither are fatal flaws.) ‘As we hiked,’ Walker starts one section, ‘I started to think about the heroic explorers.’

Issues surrounding climate change lie at the emotional heart of the book. Walker is an expert at navigating the crevasses of this treacherous field: her previous volumes include the co-written The Hot Topic (2008), which deals exclusively with warming issues. In Antarctica she handles (literally) ice cores pulled from a depth of three kilometers on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, a cold, old, dry place higher than the South Pole. Those cores, like the ones drilled from the Greenland Ice Cap, yield crucial information about previous glaciological and temperature cycles, data that helps us inch forward in our understanding of the current crisis.

In a dramatic and fascinating final chapter, Walker discusses the potentially devastating consequences of collapse in the Amundsen Sea Embayment — what she calls the continent’s underbelly. She ends Antarctica:

The sun is naturally warming as it ages and some distant day, perhaps millions of years in the future, the white continent will turn green again no matter what we do. When this happens, as it must, we humans will probably not be there to witness it. But someone or something else surely will.

Comments