As regular readers of this column will know, I am not an admirer of large exhibitions. The exhaustive is exhausting, and I refuse to believe that the general visitor can absorb the contents of a blockbuster show on a single viewing. Of course in these days of enforced leisure, more and more viewers are able to return to exhibitions (particularly if mounted by institutions of which they are members), though the time and expense involved deters those with jobs from making repeated visits. Vast exhibitions are designed to bring glory on the host museum and garner headlines as well as visitor numbers. The sheer size of them is supposed to convince ticket-buyers that they’re getting their money’s worth, but often they are left with a blurred impression of what they’ve seen rather than a coherent account. This is hardly a satisfactory outcome. However, there are exceptions.

There is always room for the truly spectacular, and the current Diaghilev show at the V&A is a splendid example of ostentatious display that actually works. The subject is a gift to exhibition organisers and designers, offering the full play of dramatic effects with costumes and sets to back it up, plus a potentially huge range of associated art work in the form of paintings and drawings. The actual selection of exhibits is both impressive and intriguing. Some of the finest things in the show are the costumes, but there are plenty of other objects to offer changes of pace and variety of interest.

The man who made it all happen, who brought the Russian ballet to Europe and America, was Serge Pavlovich Diaghilev (1872–1929), impresario and artistic director. It was he who gathered together the most influential dance company of the 20th century, who cajoled some of the greatest artists of the period to work with him — including Stravinsky, Picasso, Matisse and Chanel. It was for Diaghilev that Nijinsky leapt his unforgettable leaps, that Picasso designed his outrageous cubist costumes, that Stravinsky wrote his revolutionary music. Diaghilev was the glue that held this ‘total theatre’ experience together in its glorious and triumphal progress across the civilised world.

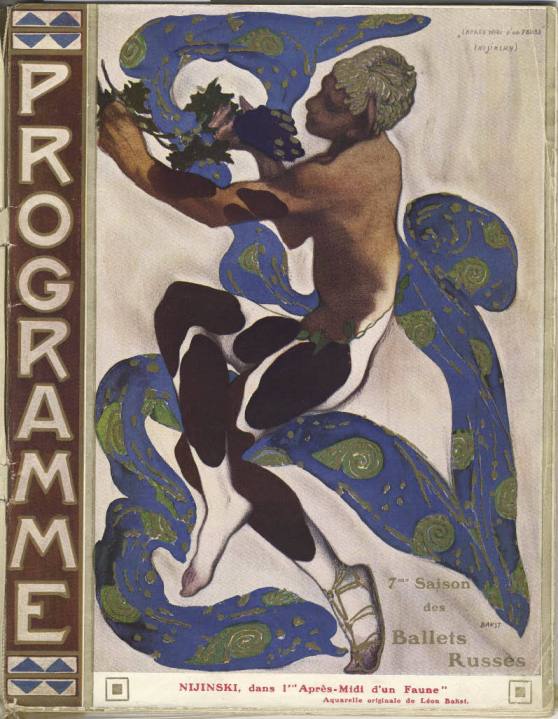

Diaghilev’s family held a vodka-distilling monopoly in the Perm region of Russia, near the northern Urals, but went bankrupt when he was 18. That early experience of living on the edge may have helped to equip him for a career of brinkmanship, an ability to balance personalities and somehow reconcile them to the common cause of art. The exhibition begins with items of Diaghilev documentary material, and sacred relics among the catalogues: his top hat, opera glasses and travelling cloak. And then comes the first taste of drama, with a group of costumes (including Karsavina’s for the role of Salome) revolving on a stand in the centre of the room. Here, too, are drawings by Benois and a large Bakst painting next to his famous costume design for the Young Rajah in the ballet Le Dieu Bleu.

The exhibition is deliciously and effectively staged throughout. There are film fragments from 1909 to indicate the kind of ballet that Diaghilev’s new style was in revolt against and all kinds of curious and beguiling artefacts, such as Una Troubridge’s plaster head of Nijinsky in L’Après-Midi d’un Faune. Heavyweight paintings are scattered amid the sketches and designs — for instance, the Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable, an oil on canvas by Degas that has always seemed to me to be more concerned with the foreground orchestral players than the background dancers.

The main problem with exhibitions devoted to ballet is that it’s difficult to take dance seriously when it’s out of context, when there’s no music and none of that suspension of disbelief which so readily engulfs the audience of a live performance. This lack is faced head-on by inventive exhibition design, particularly evident in the second section of the display, which is built to resemble a gigantic props cupboard or stage designer’s lumber room, full of black stepladders and piled-up trunks, crates and bentwood chairs. Into this darkened chamber is inserted a series of fascinating drawings: Picasso of Massine, a Larionov in blue pencil of Diaghilev and Stravinsky, a peculiarly evocative Christopher Wood of a monocled Diaghilev reflected in a mirror and framed by associates (including Wood’s friend the composer Constant Lambert), a group of ebullient Laura Knight images (two paintings and a drawing), and a couple of unexpected Ethelbert White backstage ink drawings.

Other strategies for dispelling ordinariness are the repeated appearance of the talking head of composer Howard Goodall explaining the musical developments of the period, and a chamber devoted to Goncharova’s vast backcloth for The Firebird (the largest single object in the V&A), complete with thundering music and wall projections of dancers in action. Sensational. On the other side of Goncharova’s hanging is Picasso’s great front cloth for Le Train Bleu and a couple of his costumes from Parade.

For many people, this show will be pure bliss, a place to dream and wander entranced. Shocking, then, to enter the last room and be greeted by Wyndham Lewis’s large war painting ‘A Battery Shelled’ (1919), juxtaposed with a chic House of Myrbor evening mantle. Marvellous designs by Derain, Rouault and de Chirico bring the show to a resounding finish. The accompanying hardback (special price £30), edited by the exhibition’s curators, Jane Pritchard and Geoffrey Marsh, is a lavish tribute and invaluable resource. An exhibition to be savoured.

Overwhelmed by the Diaghilev extravaganza, I missed the free display given over to the pioneering British director and designer, Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966), in Gallery 104. A great innovator and apostle of minimalism, Craig was the son of the actress Ellen Terry. A radical who used abstraction and electricity when Victorian realism and gaslight were the norm, he was, in Peter Brook’s words, ‘the origin of it all…the true influence, which we all carry today whether we know it or not’. Looks like another trip to the V&A is called for.

Comments