Perhaps it was all because of his name. John Donne: for a poet this must have felt a little like destiny, and even in the most unlikely of moments he couldn’t resist making puns. He sat down to write a letter to the enraged father of the teenage girl he had just married in secret. A lesser man might have chosen to play this fairly straight, but not JD. ‘It is irremediably done,’ he wrote to his new father- in-law, and of course he spells it ‘donne’. His young bride’s family name was More; the jokes pretty much wrote themselves. The couple had 12 children and were, he later said, ‘undone’ by their marriage.

It is difficult to read Donne and not to like him, at least some of the time. This is in part because of his insistence that even the most pious of prayers might be improved with a penis joke. It is equally because his poems invite us, to an unusual degree, to feel that we might know him. Many poets play games with identity, with whether the speaker of the poem is or is not the same as the poet. Donne does something a little different, which is to circumvent this slightly tired question with an invitation to laugh along. One famous poem pictures his mistress undressing, but it is really the speaker who is revealed: in his desperate lust, his foolishness. ‘O my America! My new-found land!’ he greets her, absurdly. Everywhere, there is something raw and exposed about him. He’s like a child who plays hide and seek by closing his eyes and shouting out here I am. In ‘A Nocturnal upon St Lucy’s Day’, which is perhaps the most beautiful poem about grief in the English language, he insists: ‘Study me then, you who shall lovers be/ At the next world… For I am every dead thing.’

Donne turns his scholars into lovers, and as a result books about him tend surprisingly often to rise up to the sparkiness of their histrionic, funny and endlessly fascinating subject. Even the driest of textual scholarship is caught up in this Donne effect. John Carey’s idiosyncratic and brilliant 1981 study John Donne: Life, Mind and Art tracks the repeated images across the poems, prose works and sermons. Even odder and also dazzling is David Marno’s Death Be Not Proud: The Art of Holy Attention (2016), which spends 300 pages in the analysis of a single Donne sonnet. The poet has been extremely well treated by his biographers. The first to write his life was his friend Izaak Walton, who was more famous for his celebrations of fishing and whose life of Donne has a good claim to be the first literary biography. R.C. Bald’s wise, deliberate John Donne: A Life was published in 1970, followed by John Stubbs’s lively and elegant biography in 2006. Perhaps, if you are playing this game seriously, it is impossible to write a bad Donne book.

Donne invented new words by breaking apart and recombining the old ones

Katherine Rundell’s Super-infinite is a wonderfully Donnean book. It sits in a long pedigree of loving, scholarly responses to the poet, but captures with an unusual wit the variety and richness of its subject. It is neither a strict biography nor only a critical engagement with his poems, but offers instead half a riff on his life and half a love letter to him. There is a lot in the life, and Rundell gives us a quick march through.

Donne was born into a Catholic family in 1572 and converted to Protestantism; he was at times a pirate, law student, MP (twice), priest and pornographer. We might see in his life a cartoonish version of the cliché about men being radicals in their youth and conservatives in their old age. As a hot young poet he wrote poems which baffled his contemporaries and were immediately copied into commonplace books. By the time he was 50 he was Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral and preacher to the king. He was rich enough to buy a Titian, and moved his old Catholic mother into the deanery with him.

Rundell is a fabulous storyteller. Her children’s books – The Explorer, The Good Thieves and others – rollick through sturdy plots peopled by lively characters: the plucky orphan, the twinkly-eyed grandfather. They leave other contemporary tales for children in their dust. She has the storyteller’s instinct that a strong narrative and a couple of fireworks can carry you through almost anything. The challenge she faces in writing of Donne’s life is that there are so many gaps. Nothing is known, for example, of the exact circumstances of Donne’s wedding. Faced with this, biographers respond in characteristic ways. Bald notes: ‘Neither the exact date nor place of Donne’s marriage is known, although a conjecture to the place is worth hazarding.’ This is so honest and so humble. Stubbs jumps over the gap: ‘By this time, Donne was married.’ Rundell is different. ‘And so they married,’ she writes, and with a flourish conjures up a whole novelistic scene, including the words spoken by the couple and a little speculation as to what the bride wore.

What Rundell values in Donne is bravado, wit, invention. He was, she writes, ‘a pure original’, and this is a wholly convincing reading of Donne. But it is also – with some irony – a familiar story, and one that previous biographers and scholars have in their own drier styles often told. Rundell observes that Donne sounds like nobody else, and that he was aware of this quality in his own poetry. ‘Donne knew that he had the seeds of something original,’ she writes, and ‘that what he was doing with the English language was fresh and different.’ To prove this, she quotes a phrase from one of his poems: ‘I sing not, siren-like, to tempt; for I/ Am harsh.’ This is a fine point, that Donne was original and knew it, and this is also a fine proof of exactly that. There is indeed something striking – even harsh – about that line-break. But the argument for Donne’s originality is itself an old one. ‘The unusualness of Donne’s poetry was quite apparent to Donne,’ writes John Carey on the second page of his book, and then proves his point by quoting exactly that same line of Donne’s.

The moments at which Rundell is a little conventional permit us to distinguish her own true invention: and through it, perhaps, Donne’s. Her innovations are rarely biographical. In a footnote, she describes Bald’s biography as ‘the bedrock of this book’, and her telling of the life draws from Bald’s version and to a lesser degree that of Stubbs, whose more recent biography she scarcely mentions. The life is a lovely melodrama, sometimes macho, sometimes Mills & Boon, but it is not really where Rundell’s interest lies. For her, his words are the magic: ‘Language, his poetry tells us, is a set, not of rules, but of possibilities.’ He invented new words by breaking apart and recombining the old ones. ‘Donne loved the trans-prefix’ she observes, and ‘he loved to coin formations with the super-prefix.’ (Carey, again, in 1981: Donne was ‘especially prone to invent verbs with the prefix “inter-’’’).

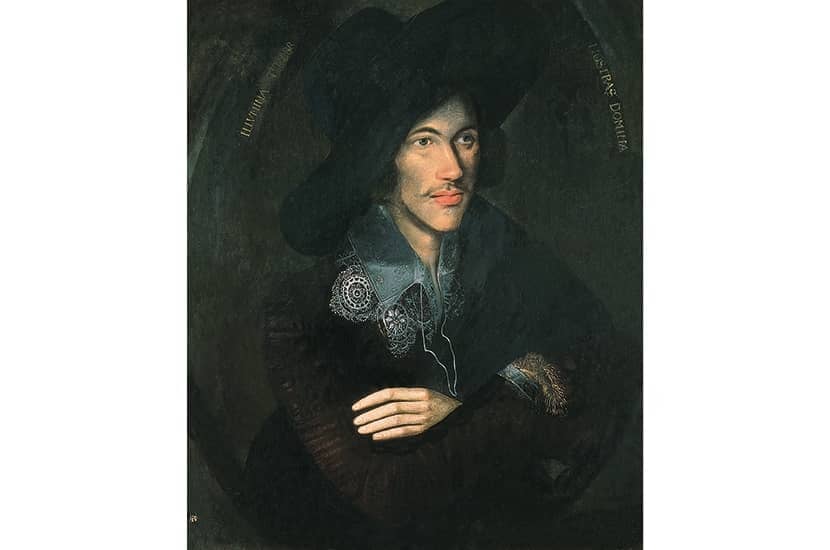

Rundell’s title Super-infinite comes from one of Donne’s own new formations, and the paradox is impatient with the limitations of language and what it can be used to describe. The book stages an often thrilling meeting between Donne and Rundell, and its basis is this supple, flexible wordplay in which sentences jump between registers and tones, between this world and the next, between everything and something more. On a portrait of the young Donne, soulful and seductive: ‘He wore a hat big enough to sail a cat in, a big lace collar, an exquisite moustache.’ On his despairs and griefs, and the deaths of his family members and too many of his young children: ‘He was a man who walked so often in darkness that it became for him a daily commute.’ On the violence of his style: ‘He wanted to wear his wit like a knife in his shoe.’

Phrases such as these do the work which literary critics are sometimes afraid to do. They attest to love, and perform that love, and in so doing Rundell returns us to a Donne who is new yet old, nicely paradoxical, his own man and everyone’s.

Comments