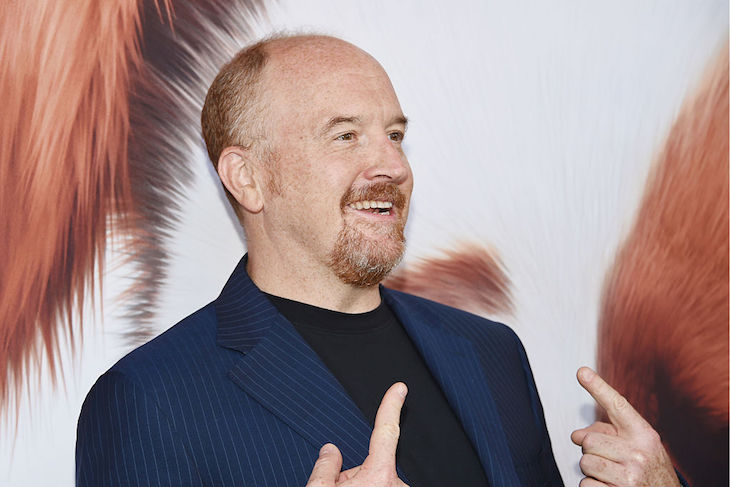

However we keep ourselves amused over the holidays this year, two sources of entertainment are off the docket. Amid the deluge of sexual misconduct allegations last month, the BBC dropped an Agatha Christie drama from its Christmas line-up after one of the actors, Ed Westwick, was accused of rape and sexual assault — which Westwick denies, slathering a layer of irony on the mystery’s title: Ordeal by Innocence. Mere hours before the scheduled premiere, the distributor of I Love You, Daddy refused to release the film, in anticipation of an ugly big reveal in the New York Times. The movie’s star, director, producer and writer, Louis C.K., now admits to having masturbated in front of multiple younger female comics (but hey, at least he asked first).

I won’t speak for the artistic merit of either work. Indeed, I cannot, as powers greater and worldlier than I have interceded on my behalf to protect me from degenerate influences. But it bears asking: who’s being punished here?

In the instance of the BBC, the licence-fee payer. We have already financed that whodunnit, and now don’t get to watch the show. Regarding Louis C.K., as a massive fan of his work, I feel personally punished. I won’t get to see his new film (reviews of which display a sharp divide, before and after the fall; the negative ones are nearly all written after the NYT outed C.K.’s serial exhibitionism, and tut-tut through the movie searching for signs that its mastermind is a perv). Worse, I am unlikely to be able to enjoy any of this comedian’s television series or stand-up sets in future. He is a bad boy who does icky things, and in this squeamish, censorious climate that means that as a performer he is probably washed up in perpetuity.

Yet this is a bigger issue than deprived-audience-as-collateral-damage. It is even bigger than our recent wholesale dumping of the concept of innocent until proven guilty; Louis C.K. confessed, but the BBC peremptorily scotched the airing of that drama long before Ed Westwick could have his day in court. There’s a defensible logic to suspending an actor — or any other employee — charged with misconduct, especially of a criminal nature, in the interest of safeguarding the accused’s co-workers. But both these productions were already in the can.

Thus the reasoning runs that in order for art to be allowed into the public marketplace, the artist must first pass a moral purity test. At the moment, we’re consumed by sexual rectitude, but the vice squad needn’t stop there. Perhaps we won’t be permitted to watch films or TV shows, read books, look at pictures or listen to music if any of the creators involved have ever displayed a

violent temper, cheated at cards, cycled through a red light, forgotten to feed their cats, drunk to excess, shoplifted (that’s you, Winona Ryder; so much for Stranger Things), snapped at small children or eaten foie gras. These days it should go without saying that any evidence of racism, Islamophobia or intolerance of gender variants must mandate that an artist’s baby be thrown out with the filthy bathwater. We should only get our hits of culture from perfect people with perfect pasts and perfect opinions.

Arguably, art is just more stuff. So we might decide to boycott these products to protest against the wandering hands that made them, just as activists with Palestinian sympathies refuse to buy Israeli goods. But in both the instances we’re examining here, an in loco parentis overlord has denied the consumer the right to make that decision. BBC viewers are not allowed to determine for themselves whether the presence of an actor accused but not convicted of assault is sufficient reason defiantly to break out the Scrabble board rather than watch a tainted Agatha Christie adaptation. Filmgoers are not free to make up their own minds about whether disagreeable revelations about Louis C.K. as a man make his work disagreeable too.

I’m a purist in another sense. I happily scarf down the popcorn at films by Woody Allen and Roman Polanski. All that matters to me is whether the movies are any good. A painter could be an axe murderer for all I care (call me old-fashioned, but I’m one of the last holdouts who believes hacking people to pieces is worse than sexual impropriety), and I would still hang the artist’s comely landscape in my house. Fine, art is stuff, and I care about the stuff. I don’t give a toss who made it, and I am resolutely incurious about the personal lives of the creators behind the films, books and artwork that I love. I want my own readers to feel the same way. Ignore me; take the novels and run. I would dread a world where to publish I had first to be certified as a nice person.

Given that the number of perfect people whom I have met is exactly zero, a moral purity test for artists is the end of art.

At least a French senator’s proposal to ban smoking in movies has been greeted with widespread derision. Eliminate all the French films in which a Gitanes makes an appearance, and all that’s left is the odd Chanel advert before the feature. Yet what leaps out for me is the eye-popping disproportion, which would be LOL hilarious if the privileging of the venial over the mortal sin hadn’t become, bewilderingly, the norm.

Consider for a moment the range of behaviours that cinema sponsors. Rape, arson and pillage. Defenestration, disembowelment, drawing and quartering, amputation and flaying alive. Hanging, electrocution and crucifixion. Enslavement, political persecution, assassination and genocide. Treachery, betrayal, humiliation and heart-breaking. Wife-beating, serial killing and cannibalism. Incest, castration, and police brutality. Mass slaughter on battle-fields or western frontiers and even in outer space. Stabbing, strangling, poisoning and bludgeoning to a bloody pulp. Oh, but never mind that. Just so long as nobody smokes.

Comments