In 1923, a Frenchman, Emile Coué, persuaded millions of Americans to finger a piece of string with exactly 20 knots. It was an exercise in auto-suggestion. At each knot of this secular rosary, the user intoned: ‘Every day, in every way, I am getting better and better.’ Sylvia Plath’s letters — until they implode on p.790 when she discovers the affair between Ted Hughes and Assia Wevill — are a similar numbing iteration of optimism and self-improvement. Thereafter, the story changes, darkens.

Up until then, her story is cropped for improvement: she takes her finals at Cambridge but the letters are silent on her degree result (II: i). She explains to her brother Warren that she doesn’t write when her moods are black. There is no mention of her fear of barrenness until she is safely pregnant with Frieda. She resumes consultations with her shrink Dr Ruth Beuscher in December 1958 — a fact disclosed in her journals, but absent from the letters.

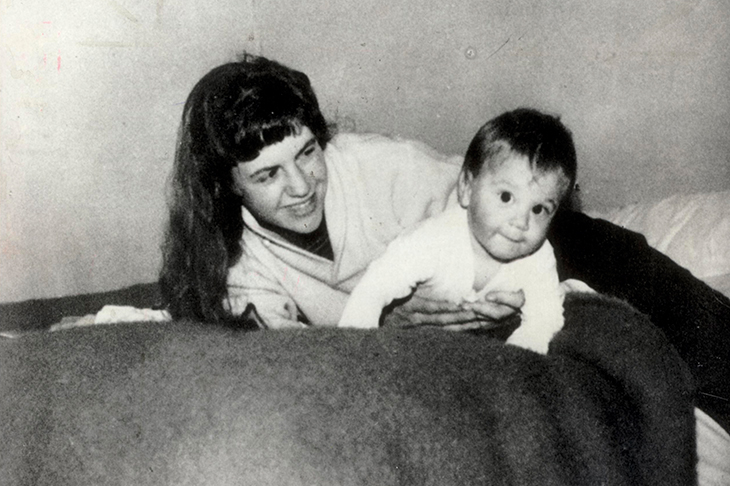

Joan Didion famously wrote that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. She should have added that we are all of us unreliable narrators. A trivial but emblematic instance: Plath’s baby son Nicholas has a squint. When he is born, Plath compares his eyes favourably with his sister’s — ‘unlike Frieda, whose eyes crossed alarmingly for a long time.’ In fact, Nick’s eye needs corrective surgery, but she doesn’t see it because she is blinded by love.

Plath was aware of her tendency to distort: ‘Do tear my last one up’; ‘Do ignore my last letters’. Like a Coué-ist, Plath persuades herself that Hughes will love America — its gadgets, its grants, its climate, its opportunities — and become an American citizen. She bangs the drum in letter after letter to her mother, Aurelia Plath, only to concede inevitably that she ‘wouldn’t have Ted change his citizenship for the world’.

Her positions are contradictory: Ted is completely indifferent to his children, ‘hates’ Nicholas, (though he visits them weekly ‘like an apocalyptic Santa Claus’) and yet is planning to steal them from her. Analysing her problems (22 January 1963), she identifies two main causes: ‘I have not been alone by myself for over two months’; ‘I must just resolutely write mornings for the next years, through cyclones, water freezeups, children’s illnesses & the aloneness.’

Ted Hughes was a Leo, Sylvia a Scorpio. They had a Ouija board called Jumbo. When Sylvia is successfully pursuing a flat in Yeats’s old house, she opens his plays at random and finds confirmation: ‘Get wine and food to give you strength and courage and I will get the house ready.’ Both partners in this tragic marriage believed in astrology and divination. ‘Fixed stars/ Govern a life’, Plath wrote in ‘Words’. Birthday Letters, Hughes’s extended account of their life together, is vitiated by the automatic invocation of Sylvia’s star-crossed fate to account for her inevitable suicide, a suicide Hughes was therefore powerless to avoid. The sequence is an act of absolution. (Assia Wevill, Hughes’s main lover, is allotted a nugatory role in Birthday Letters.) Astrology is one of the competing notions the couple happened to share. Jumbo forecast, incorrectly, that they would win the pools.

In her poem ‘The Courage of Shutting-Up’, Plath writes about wrongs as gramophone records: the needle ‘Tattooing over and over the same blue grievances’. Permanent, compulsive. One of her repeated, exhausting scenarios is the schema of barren women — that Ted is drawn to the childless, to Dido Merwin, to his sister Olwyn, to Assia Wevill (otherwise ‘Weavy Asshole’). In Plath’s account, Assia has had so many abortions that she is infertile. (Assia of course became pregnant after Plath’s suicide.) Then there is the template of her father Otto Plath: his death and desertion account for her insecurity with Ted, her need to police his every movement.

Plath’s letters repeat, refine, revise, reinforce and amplify a narrative until it is a word-perfect recitation of wrongs. Little Frieda has been ‘diagnosed as a latent schizophrenic as a result of this’. And Hughes has his own version which, as he sees it, is annexed by Sylvia’s of babies, domesticity and sexual fidelity. His animal nature — a central Hughesian myth — has been nullified. His accusation reported by her: ‘This is a Prision [sic], I [Sylvia] am an Institution.’

The problem is that he is attracted to other women and they are attracted to him — and Sylvia is aware of it, threatened and aggressive. ‘I am sick of being suspicious.’ In her journals, she is jealous of the 16-year-old Nicola Tryer in North Tawton. There is a vivid account of her on the lavatory and dragging on her dungarees when she hears Nicola downstairs. Dido Merwin’s memoir describes how Sylvia tore up ‘all Ted’s work in hand: manuscripts, drafts, notebooks, the lot’, because he was half an hour late from a meeting with Moira Doolan, the head of the BBC Schools Broadcasting Department. She ‘also gralloched his complete Shakespeare’.

To her psychiatrist, Dr Beuscher, Sylvia volunteers a milder account of her actions and a more incriminating account of his:

Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage: the baby I lost was to be born on his birthday. I thought this an aberration, & felt I had given him some cause, I had torn some of his papers in half, so they could be taped together, not lost, in a fury that he made me a couple of hours late to work.

He was to babysit Frieda. Moira Doolan and his Shakespeare, more or less reduced to ‘fluff’, are edited out. Is it cynical to detect in that otiose ‘physically’ the anxious pedantry of the perjurer? In every previous mention of her miscarriage (6 February 1961), the reason is said to be unknown, but possibly caused by her appendix which was removed three weeks later. Dido Merwin is aware of Sylvia’s version but doesn’t believe it.

There is another major discreditable thing in the Hughes record: he wished her dead, thought she might commit suicide —and said so. I think this is highly likely. But we need to understand it. Neither person was themselves. A minor symptom of this is that both became smokers under the strain of separating. They hated smoking, Sylvia especially. A feature of their break up is Sylvia’s persistent complaint that Hughes had become a liar. She returns to this again and again. And the complaint wasn’t presumably restricted to her correspondence with others. She asked for ‘the truth’. And eventually got it. Everyone has intrusive thoughts. No one is immune from them. They are repressed as a general rule — unless we are goaded into expressing them.

Which brings me, finally, to the notorious, suppressed letter to Aurelia Plath about Hughes’s sister Olwyn. Olwyn evidently told Sylvia a few home truths about her bossiness, her self-centredness — as you do at Christmas — and Sylvia walked out onto the moors, had to be rescued, and returned to London the next morning early with her entire family. Olwyn apologised as she left.

There is now another account to Dr Beuscher. Psychoanalysis has a lot to answer for. An episode of bad temper and frankness is given Freudian spin by Sylvia. She mentions that Olwyn (aged nine) and Ted (aged seven) shared a bed as children. She floats the idea that Olwyn obliterates her socially in order to displace her as Ted’s wife. The idea of actual incest is absurd but it is introduced as a ghost narrative — to ‘explain’ the intensity of Olwyn’s dislike.

But maybe Olwyn just wouldn’t accede to Sylvia’s drive for perfection — and sensed that Sylvia looked down on her family: ‘they are inhuman Jewy working-class bastards’ (16 October 1962). Four months after this epitome, she gassed herself, gripped by the dominant narrative of her madness and the ineradicable suicidal tendencies that fuel her great poems.

Comments