For much of the second half of his life Arthur Miller was a man whose future lay behind him. The acclaimed American playwright, celebrated for classics such as The Crucible, All My Sons, A View from the Bridge and Death of a Salesman, struggled to get his later plays staged in his own country. When occasionally they were put on they were fiercely attacked by most critics, who thought them tedious, preachy and ill-written; as one typically said of Incident at Vichy, it was ‘the same old noisy virtue and moral flatulence’. Miller, they decided, was a relic of the postwar era, stuck in the ideological struggles of the past, and totally out of touch with the modern theatre.

Yet while he was marginalised on Broadway, where moral seriousness was almost a sin, in Europe his plays were widely staged and enthusiastically received. This was especially the case in the UK, where audiences were clearly more ready to accept the theatre as a place where social and political issues could be explored. Directors and actors at the National, the RSC and the Young Vic readily embraced his work, both new and old.

These years were also marked by his unceasing activity in the public arena. Previously a persistent signer of petitions and letters of protests, he now became directly involved in political action. He was a major player in the anti-Vietnam war movement, and an outspoken and eloquent critic of the foreign policies of successive presidents, from Lyndon Johnson to George W. Bush. Perhaps his greatest achievement lay in his work for the writers’ organisation International PEN. As its president for four years he campaigned tirelessly for justice for dissident writers suffering imprisonment under repressive regimes, in Russia, Czechoslovakia, China and elsewhere.

This second half of Christopher Bigsby’s masterly and illuminating biography has all the virtues of the first. Rich in compelling detail, comprehensive in its coverage of his subject’s private and public life, it tells Miller’s tale with a fine narrative sweep and a sure grasp of the changing political background. While clearly sympathetic to his subject, Bigsby is not afraid to make criticisms, or to lay out clearly the arguments of Miller’s detractors. He’s an astute interpreter of the plays and of Miller’s dramatic intentions, while his interviews with directors and actors involved in productions on both sides of the Atlantic provide valuable glimpses of Miller the craftsman in rehearsal.

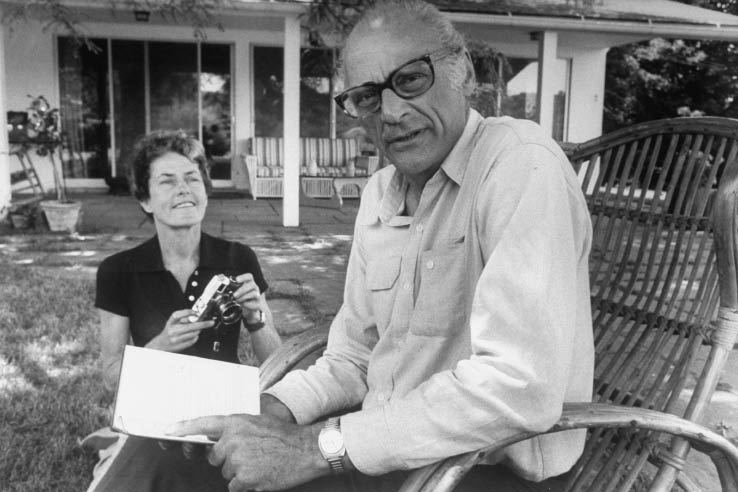

The earlier book ended with the collapse of his celebrated marriage to Marilyn Monroe; the present volume focuses on his blissfully happy union of 40 years with Inge Morath. A skilled and sensitive photographer with Magnum, a former lover of Henri Cartier-Bresson, she travelled all over the world, sometimes with Miller, sometimes alone. After Marilyn Monroe’s excessive dependency, her independent character was clearly what Miller needed: she transformed his life, helping him at a critical time to regain his emotional balance and to resume his writing.

Given exclusive access to Miller’s notebooks and his unpublished works, Bigsby charts Miller’s highs and lows in exceptional detail. It’s a surprise to read that, by his own reckoning, he abandoned some 90 per cent of what he wrote. Despite his apparently confident public persona, he experienced many periods of depression, though not only as a result of the disdain poured on his plays. ‘There are times when you feel the whole weight of mankind on your shoulders,’ he once confessed.

Guilt about his past — notably his failure to fight in the Spanish civil war or the second world war, and his espousal of communism — was one motor for his plays. Surprisingly for a Jew, the Holocaust only gained his full attention after Inge Morath (whose father had been a Nazi) took him to Mauthausen concentration camp, and he attended the trial of several Auschwitz administrators and guards. After that, directly or indirectly, it often fed into his plays.

There are valuable testimonies from his daughter Rebecca and his sister Joan, both of them clear-eyed and eloquent in assessing his character, flaws and all. We see him at ease in his Connecticut home, planting trees and making furniture, or successfully intervening in the case of a local boy wrongfully accused of murder. Bigsby also deals sympathetically with the traumatic episode of the Down’s syndrome baby, and the couple’s much criticised decision to place him in a home.

Despite the critical brickbats in America, Miller showed remarkable resilience and persistence, continuing to write into his eighties, believing his time would come again. He was right. Beginning in 1984 with a revival of Death of a Salesman, starring Dustin Hoffman as Willy Loman, Broadway began belatedly to make amends. Today, as Bigsby reminds us in this superb testament to a great playwright and a fascinating human being, ‘there is never a moment when an Arthur Miller play is not being staged somewhere in the world’.

Comments