Among the many curiosities revealed in this book, few are more startling than the fact that at the height of the so called ‘summer of love’ in 1967 the British historian Arnold Toynbee, on a visit to San Francisco, made his way to the Haight-Ashbury district — hippy central — to catch a concert by one of the Bay Area’s most popular bands, Quicksilver Messenger Service. Just what Toynbee, who was 78 at the time, made of the group’s epic exercise in free form, psychedelic improvisation, ‘The Fool’, Goldberg does not mention. But he does tell us that elsewhere in the Haight, at around the same time, Dame Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev were being busted at a party where pot was being smoked, and that Nureyev ‘performed a jeté into the back of a police van’.

By then the Haight, as the district was known, was to all intents and purposes finished. Hippies had been the subject of a cover story in Time magazine, and the Haight was fast being populated by teenage runaways, panhandlers, drug dealers and assorted charlatans, a human zoo for gawping tourists in Gray Line buses, pausing only to buy ‘Love Burgers’ from an enterprising merchant.

The summer of love was giving way to the winter of exploitation. In October 1967, a group of community ‘elders’ organised a mock funeral procession through the Haight to mark the passing of ‘Hippie, devoted son of the media’, suggesting that from now on the acceptable term would be ‘free men’. It would never catch on.

San Francisco, flowers in your hair, free love — it all seems as remote and unreal as a fever-dream.

Danny Goldberg was a teenager in the 1960s, growing up in New York in a liberal Jewish family. He was exposed to drugs and student radicalism, became a rock journalist, then a record executive and the manager of Nirvana. Old enough to have savoured 1967 without fully digesting it, he has written a book that sits halfway between social history and memoir.

He describes how a multitude of different elements — the fight for civil rights, the war in Vietnam, folk protest music, a growing disenchantment with materialism and all forms of authority — began to coalesce to create a single ‘movement’, if one can describe something so inchoate, amorphous and varied in its ideas and objectives as a movement, that would come to constitute what Arnold Toynbee called ‘a red warning light for the American way of life’.

The seedbed for the movement was the Haight — a neighbourhood of run-down, Victorian wood-frame houses, settled by artists, musicians and bohemians.

The principal catalyst, of course, was drugs, notably LSD. The author Ken Kesey, who had first sampled the drug as a volunteer for hospital tests being conducted surreptitiously on behalf of the CIA, spread the word through a series of ‘acid tests’ in and around San Francisco, at which the Grateful Dead acted as informal house-band.

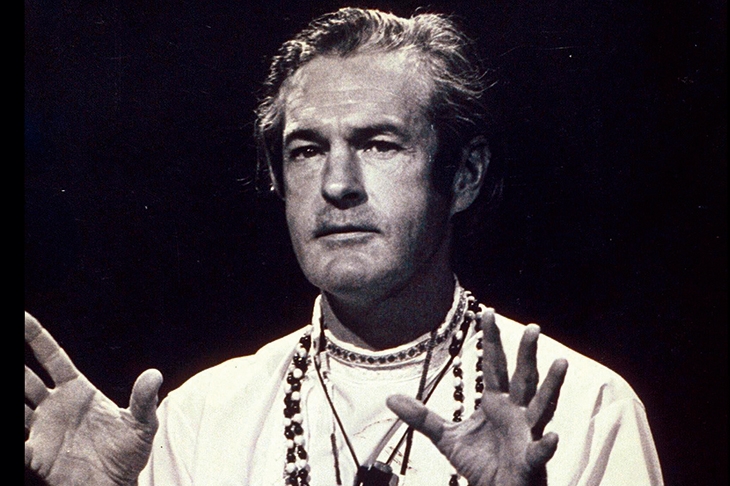

In October 1966, the American government outlawed LSD. Three months later, in January 1967, more than 30,000 people gathered in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park to protest against the new law at the first ‘Human Be-In’, or ‘Gathering of the Tribes’, as it was called: the tribes, in this case, being hippies from the Haight, anti-war radicals from across the Bay in Berkeley, unreconstructed Beats from an earlier generation, Hells Angels, assorted free-thinkers and oddballs and the Diggers — an anarchist group, named after the 17th- century English radicals, who advocated the abolition of money and pioneered free food programmes on the Haight. It was at this gathering that Timothy Leary uttered what would become the mantra of the movement — ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’.

Ronald Reagan, in 1967 newly installed as governor of California, defined a hippie as someone ‘who looks like Tarzan, walks like Jane and smells like Cheetah’. Goldberg offers a more positive definition. It was to strive to be ‘a happy and good person’, observing the moral imperative to fight for civil rights and against the war, and abide by ‘the spiritual notion that there were deeper values than fame and fortune. Peace and love’. As a movement it was Dionysian, idealistic, utopian, spiritual without being conventionally religious. The term Goldberg uses to summarise the prevailing mood is agape — the Greek word distinguishing universal love from interpersonal love (eros).

Goldberg recounts his own epiphany after taking LSD for the first time — not the quasi-religious experience described by Kesey and that other apostle of acid, Timothy Leary, but a more down-to-earth realisation that, having been brought up to believe that everything in life was ‘deep’ and ‘serious’, drugs gave him ‘permission to be happy’.

Goldberg writes in a style that is more methodical than inspired, and he is clearly more interested in some aspects of the era than others. The chapters on music — and this is strange, given his own background — are curiously perfunctory, the pen portraits of leading artists of the day such as the Grateful Dead, Phil Ochs and Country Joe and the Fish as devoid of colour and animation as Wikipedia entries. Faced with having to say something about the most significant recording of 1967, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Goldberg simply gives up, admitting: ‘I have nothing to add to the thousands who have analysed the album’s music.’

The rise of the Black Power movement — Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali (‘idolised by pot-smoking hippies’) and race riots — and the growing interest in eastern religions are dispatched in a similarly desultory manner. There is much in this book to digest —rare is a volume whose index includes Thoreau, Chogyam Trungpa, Billy Graham, the Black Panthers and Donald Trump. But it suffers from the lack of a developing narrative, and often seems stilted and episodic.

One of the more striking aspects of the era was how the erosion of traditional forms of authority created a vacuum into which other forms of authority, both benign and malignant, could enter. Haight was full of lost sheep in search of a good shepherd, and street-corner gurus, cults and instant religions flickered like moths around a bright light.

It was a setting in which a sociopath and conman like Charles Manson could, and did, flourish. Manson recruited his ‘family’ of drug casualties and runaways on the streets of the Haight.

In the haze of good intentions and unrealisable goals — free love, the abolition of money, the end of war, universal peace and harmony — and a movement ‘rudderless in the current of its convictions’ (as another writer on the period, Richard Goldstein, has described it), the abiding question was, who was in charge?

The answer, of course, was nobody. The Diggers disdained the hippies and the radicals. The radicals, exemplified by the self-styled cheerleaders of the movement Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, disdained the hippies for their abdication from ‘serious’ political work. The hippies just wanted everybody to love everybody else and thought the radicals were just the same old control-freaks in new costumes.

Jerry Garcia, the good-humoured leader of the Grateful Dead, was appalled when at the Human Be-In, Jerry Rubin mounted the dais and started haranguing the crowd about the need for political protest:

It was every asshole who told people what to do. The words didn’t matter. It was the angry tone. It scared me. It made me sick to the stomach.

Goldberg offers a lovely description of a gathering of the movement’s ‘elders’, held in February 1967 on the houseboat of Alan Watts, the English Zen Buddhist, and including the poet Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. At issue, as Watts put it, was the question of whether to ‘drop out or take over’. Ginsberg pointed out to Leary that while he might have dropped out of his job as a psychology teacher at Harvard, he had multiple safety nets that would never be available to the vast majority of teenagers who were taking acid and trying to figure out how to function in the world while ‘staying true to their new selves’.

‘What,’ Ginsberg asked, ‘can I drop out of?’

‘Your teaching at Cal,’ Leary snapped back.

Ginsberg chuckled. ‘But I need the money.’

The meeting moved on to discuss the emergence of ‘an ecological conscience’ and how the new version of humanity would abandon the cities for the countryside. ‘There will be deer grazing in Times Square in 40 years,’ Leary prophesied, with characteristically fanciful inaccuracy. (Goldberg harbours a respect for Leary, whom Richard Nixon hysterically called ‘the most dangerous man in America’, that borders on the worshipful, although readers of this book, and Robert Greenfield’s definitive biography, are more likely to conclude that Leary’s messianic faith in LSD as the sacrament of ‘the religion of the future’, and his own role as high priest, shows just how deluded and egotistical he really was.)

Nobody could answer the basic, practical question of how to deal with the thousands of teenagers descending on Haight, ‘not knowing where they’re at’, turning the putative City on the Hill into a scene of crime-ridden squalor.

What Goldberg’s book vividly illustrates is that there was much that was foolish, misguided and naive about the hippy movement (the origin of the hippy folk myth that smoking bananas would get you high is chronicled here in exacting and hilarious detail). But there was also much that was innocent, and pure, borne of what Goldberg calls ‘communal sweetness’. And what makes this book ultimately beguiling is its absence of cynicism, and Goldberg’s touching faith in the original hippy idea.

He tells a story of how in 1967 he was barefoot at San Francisco airport, trying to get on a plane to return to New York for Thanks-

giving. An airline employee told him that he could not board the plane without shoes. Spying a young man with long hair, Goldberg explained his predicament and asked to borrow his shoes. The young man gave them up unhesitatingly. ‘I am still not sure what is more remarkable,’ Goldberg writes; ‘the fact that he gave his shoes to a stranger or that I had the certainty he would do so. I am equally certain that this would not have been possible a year later.’

He does not recount whether he returned the shoes.

Comments