In 1905, shortly before the world première of The Merry Widow, the Viennese theatre manager Wilhelm Karczag got cold feet and tried to pull it. He offered Franz Lehar hard cash to withdraw the score, and when that failed, he rushed it on under-rehearsed, using second-hand sets from an older show. Or so the story goes anyway. Karczag couldn’t know that within a decade The Merry Widow would become the most successful piece of musical theatre in human history up to that point: an all-conquering global brand that gave its name to hats, corsets, cigarettes and a rather nice cocktail (equal measures gin and vermouth, splashed with absinthe, Bénédictine and bitters, in case you’re curious). In the 1920s an American firm even marketed Merry Widow condoms.

In the 1920s an American firm even marketed Merry Widow condoms

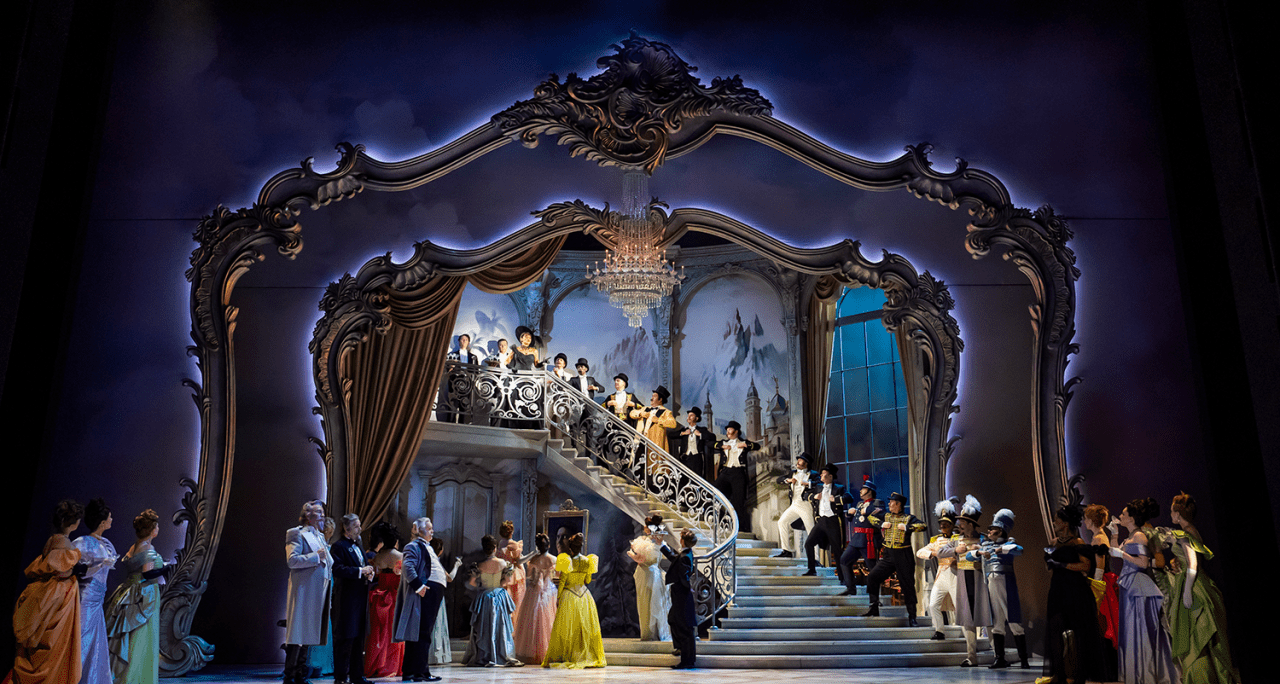

I didn’t manage to check the Glyndebourne gift shop, but there was never much likelihood of them selling the Widow short. Cal McCrystal’s new staging is a sugar rush for the eyes; a gorgeous, rose-tinted swirl of belle-époque opulence, framed (thanks to Gary McCann’s designs) in an ornate silver frame that doubles as a cinema screen. The cast and titles are projected as the Prelude plays (it’s performed in English, by the way), as if we’re about to watch some classic movie musical. Men in gold braid and tailcoats line a grand staircase, doffing their hats in unison. Mist cascades downstage as Hanna (Danielle de Niese) and Danilo (German Olvera) sing a moonlit love duet. You get the idea: McCrystal has said that he had MGM in mind, and he delivers in spades.

And then Olvera trips drunkenly at the top of that staircase, tumbles head first down its entire height and lands flat on his face at the bottom. That’s the other thing: McCrystal is known for a particular brand of (often broad) physical comedy. He deploys his signature moves relatively lightly here: groan-inducing sight-gags aimed at a crowd of a certain age (ambassador, you are spoiling us!) flit by, raise a giggle and are gone. Some are played for belly-laughs – Sir Thomas Allen, making hay as the creaky Baron Zeta, gets progressively more shattered as his sprightlier co-stars toe-tap their way through successive encores. Others – like Olvera’s epic tumble – are delivered with such spontaneous virtuoso grace that they border on the sublime.

But that’s operetta: a tightrope walk between the exquisite and the absurd, high art and outright farce. McCrystal and his cast (and how he found a performer who combines Olvera’s vocal and acrobatic skills is a marvel in itself) walk that tightrope with panache, and with only one significant wobble. The Act Two ‘Pavilion’ duet might be the most ravishing five minutes of music in Silver Age operetta, and Michael McDermott (Camille) and Soraya Mafi (Valencienne) play their B-plot couple as loveable, vulnerable human beings rather than comic relief. Then they retreat into the garden pavilion where McDermott is seen in silhouette doing… well, no spoilers, but let’s say that McCrystal, confronted with an extended stretch of slow music, sometimes struggles to keep his hands to himself. I winced; everyone around me roared. My loss, probably.

In the pit, meanwhile, John Wilson and the London Philharmonic were conjuring sounds of molten silver and blushing velvet – orchestral playing that was light on its toes but always ready to lean in with a smile and a caress.

De Niese’s wide eyes, megawatt smile and broad-brush acting are pretty much as expected from this artist, and no one would call her singing focused exactly. But then, Hanna Glawari is no aristocrat, and a certain madcap charisma has always been part of her make-up. Sudden, darted glances at Olvera convey their romantic backstory just as revealingly as the poignant, bittersweet asides with which Lehar seasons his score. And in ‘Vilja’, Wilson and the orchestra surrounded de Niese’s soprano with veils of whispering strings to generate an endless sense of space and longing. Go and see it: you’ll have a wonderful time.

That’s one way to do operetta. Things typically skew a bit grungier at Wilton’s Music Hall, and John Savournin’s Charles Court Opera is unrivalled at generating musical-comedy magic on a microscopic budget. With a piano accompaniment and a single pastel-coloured set, Savournin’s new staging of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Sorcerer still has everything it needs to make the show dance and the audience laugh.

You could single out the singing of Ellie Neate as Aline, or the faintly unhinged goofiness (think Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka) of Robin Bailey as her sweetheart Alexis. Or, indeed, Savoy legend Richard Suart, gloriously raddled in the title role: a long-established Family Sorcerer from a reputable provincial firm who uses a teapot to brew his love potion. But the whole company exudes the same generosity and wit – and has the voice and the comic chops to back it up. Ultimately, that can’t be bought.

Comments