In so far as it acknowledged them at all, the Chinese Communist Party has blamed ‘infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces’ for the recent anti-lockdown protests. It’s an accusation laden with historical baggage. Modern China’s history with foreign states, especially the Europeans, hasn’t generally been a happy one. For many Chinese, the collective memory is still raw.

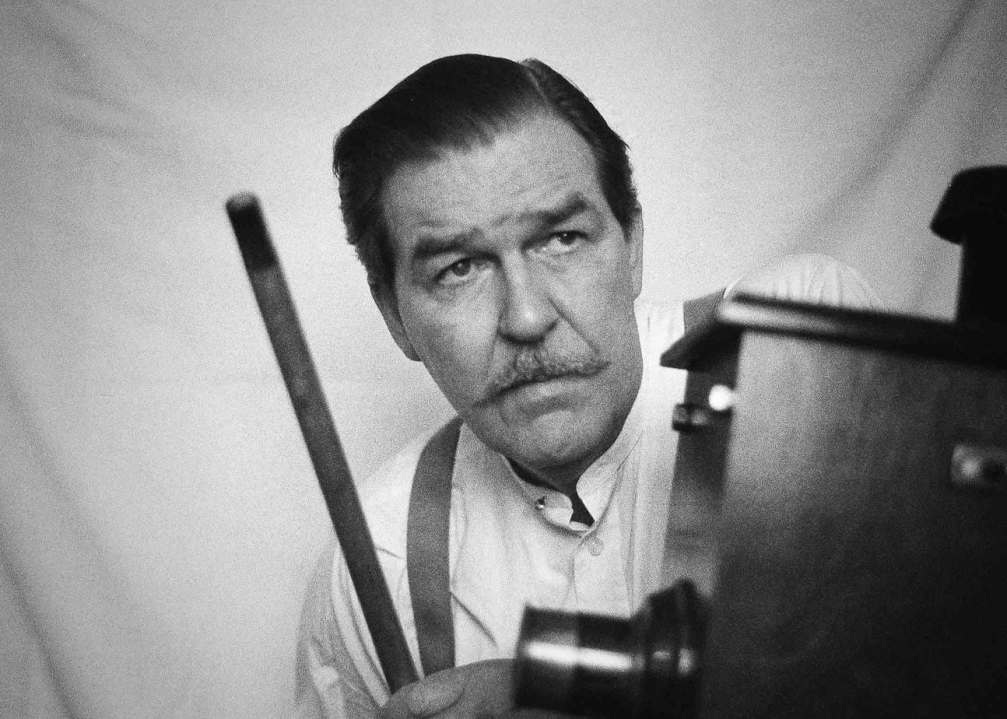

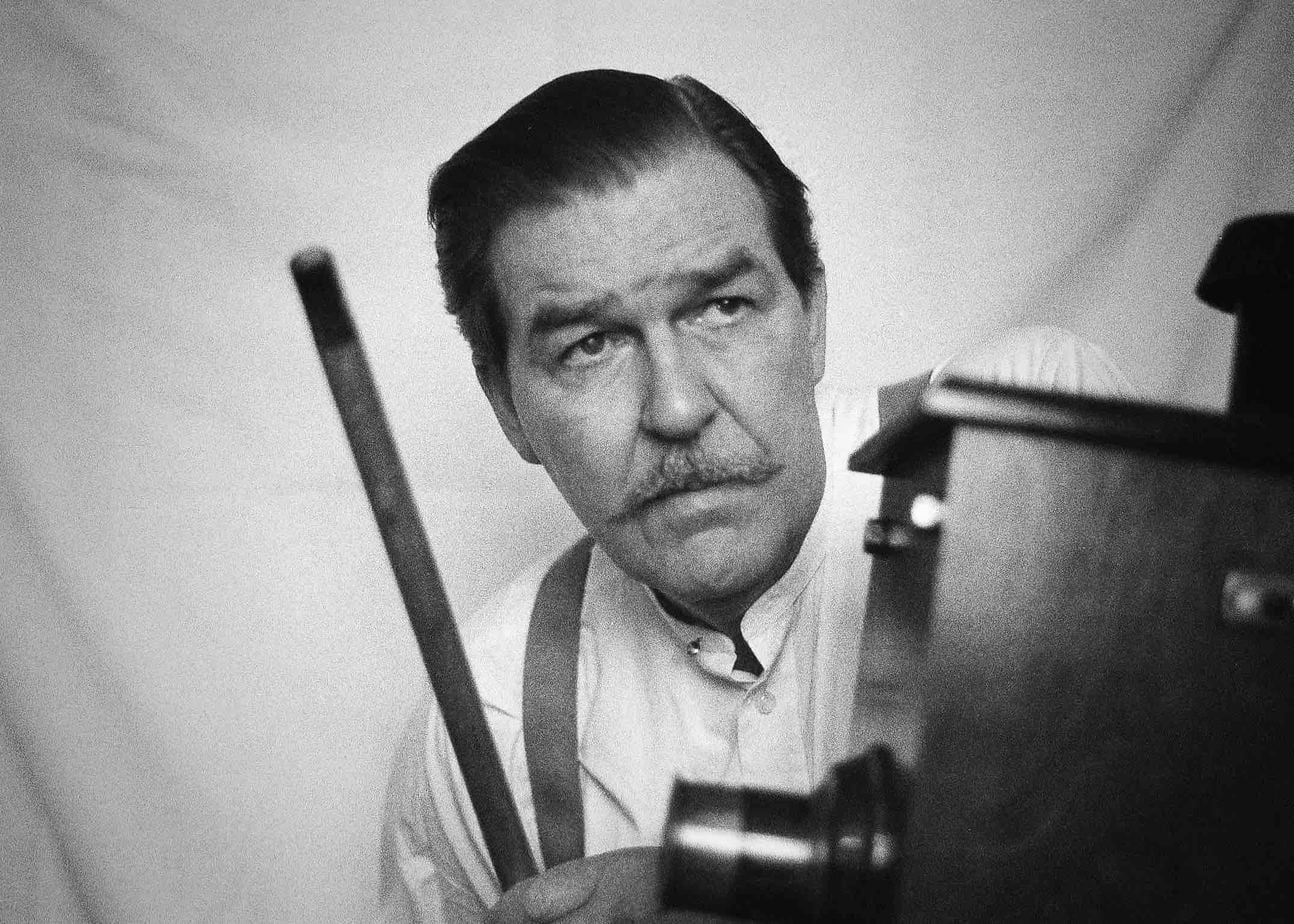

The most mutually traumatic episode in this history is probably the Boxer Rebellion, when thousands of foreign delegates were besieged in Beijing by Chinese rebels for 55 days. The siege eventually ended with an allied rescued mission which sacked the city, the soldiers raping and killing the Beijingers who were left. This episode is the subject of a new one-man play by a veteran China hand. Mark Kitto manages to deliver an intelligent and humorous show despite the rather violent subject matter. He plays a British diplomat, then a Qing general and finally a Welsh foot soldier of the relieving forces.

It’s a play full of political astuteness for those interested in China’s relations with the West today. ‘China is sick, infested with foreign bodies’, Rong Lu, Kitto’s Manchurian official, observes, sounding not so different to his political successors in the CCP. And yet, ‘in my opinion we – Britain and the “West”, as it is coming to be known – have got China wrong’, impresses Sir Claude MacDonald, Britain’s man in Beijing during the siege and Kitto’s first character. Plus ça change.

Could this play help us better understand China? It’s certainly a good start.

For one, Chinese Boxing doesn’t shy away from the reasons why later Chinese call that period ‘the century of humiliation’. From the parcelling out of the country to the violent put down of the Boxers, the show describes the events that today feed China’s righteous anger. ‘What will you take this time? How many more ports? What will you burn in Beijing? How much more of your religion do we have to swallow, your drugs, your rules, your stupid clothes, your damned railways, your stinking food?’, Rong Lu questions the audience. It’s no surprise that this is the part of history that I, as a schoolchild in China, learned most about. The so-called ‘Eight Nation Alliance’, which broke the siege, was a bogeyman, the very epitome of foreign bullying.

Of course China has not always rebuffed foreigners. Even during those decades of chaos, students chanted for ‘Mr Science’ and ‘Mr Democracy’, inspired by the western political systems they were coming into contact with. It was Japan that sheltered exiled Chinese republicans who later formed the Kuomintang and it was in the foreign concessions of Shanghai that a free Chinese press bolstered the early ideas of Chinese Communism. Modern China is built on positive foreign influence more than its nationalist leaders like to admit.

Kitto knows first hand just how contradictory Chinese attitudes towards the foreign can be. He first visited China in 1986, one of the first westerners to enter the country after the doors were shut with the Communist takeover. He moved there in 1996, married a Chinese woman, set up a magazine aimed at other foreigners in China, and then a guesthouse in the mountains outside Hangzhou. But by 2012, he was thoroughly disillusioned with modern China and returned to the UK. His publication had been appropriated by the state, a fate which may also befall his guesthouse at the pound of one official stamp, and he was concerned that his children do not grow up under Communist propaganda. Rong Lu seems to chastise Kitto’s younger self: ‘There are foreigners in the Legation who speak Chinese so well they could pass for a Chinese. Imagine that. A foreigner pretending to be Chinese. Shabi [stupid idiot]’.

But as this self-written play shows, something of the country remained in his bloodstream. Kitto’s bilingualism offers some playful opportunities: upon seeing the audience, Rong Lu calls us yangguizi (foreign devils) which he translates to ‘honoured foreign guests’. And refreshingly, Kitto doesn’t shy away from the language of the time: ‘We’d take shots at [the Chinese] but jolly hard to hit such a small target’, Sir Claude explains. Neither is this political incorrectness all reserved for the natives: ‘No plan survives first contact with the French, and that’s when they’re on your side too’, Kitto’s Welsh sergeant opines. The white-haired members of the Army and Navy Club, where I saw the play, enjoyed it immensely.

More than a century on, China is closing to the world again. And in many ways the West doesn’t understand it any better than it did at the turn of the 20th century. A good way to dispel some of this ignorance is to drop in on Mark Kitto’s Chinese Boxing.

Find upcoming performances of Chinese Boxing, and information on how to host the play, at www.chineseboxing.co.uk

Comments