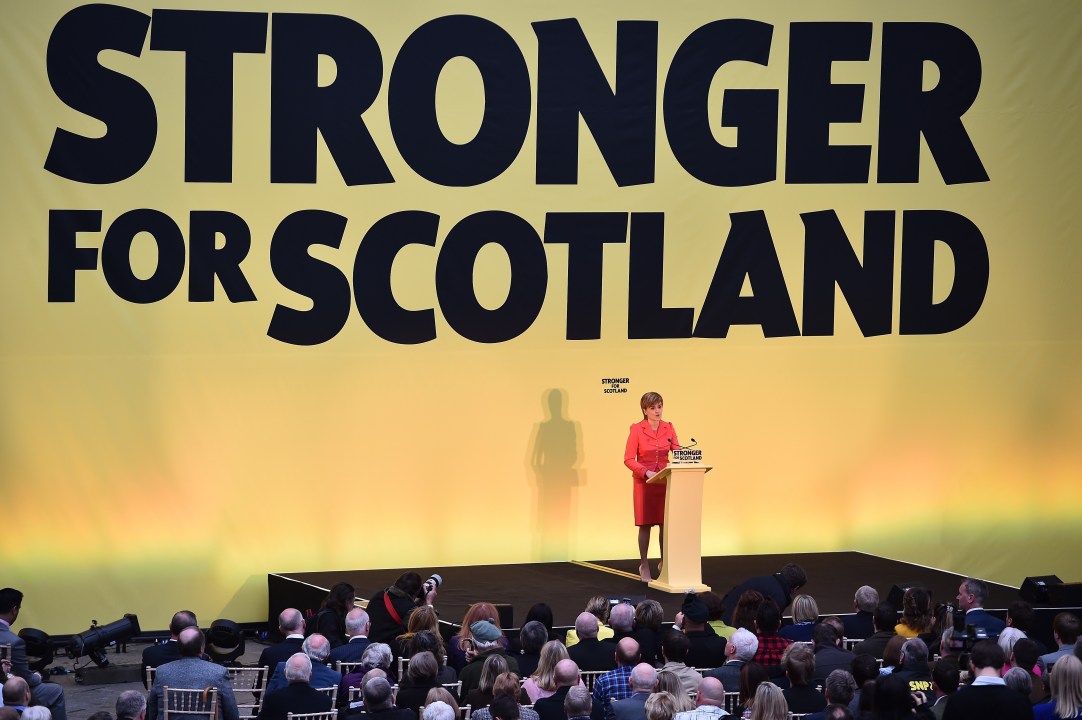

For decades now the SNP have thirsted for the moment when they can be ‘relevant’ to the outcome of a Westminster general election. Well, they have that relevance now. Never before has the launch of their manifesto attracted this kind of attention. Then again, never before has the SNP had realistic hopes of becoming the third largest party in the House of Commons.

But strength is often just weakness disguised and, once again, more than one thing can be true at the same time. And the truth is that the SNP’s position is both remarkably strong and much weaker than many people assume.

I still don’t believe that the nationalists will win 50 of the 59 seats they are contesting but I concede that my faith in this belief is a little weaker than it was a fortnight ago. It has to be reckoned possible even if not yet probable. I still suspect that the SNP will win a majority of Scottish seats but Labour will cling on to more constituencies than the polls currently suggest.

As election results go, this one has the potential to be shattering. But, curiously, it may have rather less impact on the next government than is commonly assumed.

Equally unusually, this is an election in which, though they won’t tell you so, the parties actually agree on more than they are letting on. That is, a vote for the SNP is, in the end, a vote for a Labour government. Albeit a vote once-removed. This is the SNP’s great victory in this contest. The only people disputing this are the Scottish Labour party and their reasons for doing so should be obvious to anyone who has paid any attention to this election.

Their southron colleagues would obviously prefer to see Labour hold on to as many of their Scottish seats as possible but they also recognise, surely, that they may well be able to govern without the presence of many Scottish MPs.

The Tories, of course, have been playing a double-game, raising the spectre of a Labor government propped-up by SNP support to rile English voters while, at the same time, chuckling about Labour’s Caledonian difficulties because, well, there’s nothing so cheering as your opponent’s distress.

As for the SNP, well, their entire campaign is based upon their desire to avoid the traditional Westminster squeeze that has limited their gains in the past. They need to defeat the Labour mantra that a vote for the SNP is, in the end, a kind of vote for a Tory government. Persuading voters that this is ultimately a choice between Ed Miliband and David Cameron remains Labour’s best, if these days discounted, card.

Which, of course, is why Nicola Sturgeon has been so determined to make it clear that a vote for the SNP is a vote for a Labour government, albeit, in some sense, a better Labour government than might otherwise be on offer. (She’s also, of course, pinching as many Labour policies as she can.)

Doubtless it is but the SNP don’t actually want to be in government in London. They want to avoid that complication. For doing so will allow them to run against London in next year’s Scottish parliamentary elections (elections which are, in a constitutional sense, more important than this election).

Trident? Full fiscal autonomy? These are demands that are not supposed to be met. They are, instead, issues designed to give the SNP the opportunity to claim no-one else will ‘stand up for Scotland’. Only the nationalists have the national interest at heart, you see, and it’s just such a damned shame the Unionist parties won’t give Scotland what she wants.

I asked a senior SNP strategist about this recently. What, I wondered, would you do if, say, the Tories offered you full fiscal autonomy? Could you really walk away from that kind of deal? Ah, he said, but if the Tories did that they wouldn’t be behaving like Tories so the problem does not arise because the Tories can’t and won’t do anything of the sort. Besides, they’re the Tories, you see.

It’s true that this remains an improbable offer, not least because it would have to be made over Ruth Davidson’s head. Nevertheless it also demonstrates the peculiar post-election weakness of the SNP. Because the party has put itself in a position from which it actually has very few options. It has to support Labour.

Sure, they SNP will snipe and grumble and try to extract concessions and where these are made they will be happy even as they move on to complain about what Labour aren’t offering. But, still, in the end, they have nowhere else to go.

They can’t bring down a Labour government. So why should Labour offer them anything at all? After all, even as Labour try to hug the SNP close in Scotland (Patriotic Labour!), so the SNP move to limit their policy differences with Labour. The nationalists want to increase taxes too, now.

Labour can get what they want from the SNP because the Nats have willingly given themselves no other options. At the same time, the SNP can make impossible demands knowing that even though they cannot and will not destroy a Labour government doing so will, in the longer-term, strengthen the SNP’s strategic interests in Scotland.

It suits both parties, in other words and makes it more clear than ever that David Cameron’s days as Prime Minister are most probably drawing to an end. That’s been evident for some time, however, and, curiously, does not actually depend very much upon the election result north of the border.

And if something turns up to keep the Tories in power? Well, in that event the SNP will give a very convincing impersonation of a lachrymose crocodile. What a glorious disaster that will be for their cause.

Comments