The Potteries are one of the strangest regions in the British Isles, and Matthew Rice’s The Lost City of Stoke-on-Trent celebrates their extraordinary oddity.

The Potteries are one of the strangest regions in the British Isles, and Matthew Rice’s The Lost City of Stoke-on-Trent celebrates their extraordinary oddity. Much of his text reads more like a diatribe than a celebration, for words like tawdry, grimy, unlovely, brutish and lumpen scatter his pages, and he sometimes soars to the height of invoking the term ‘tragic’.

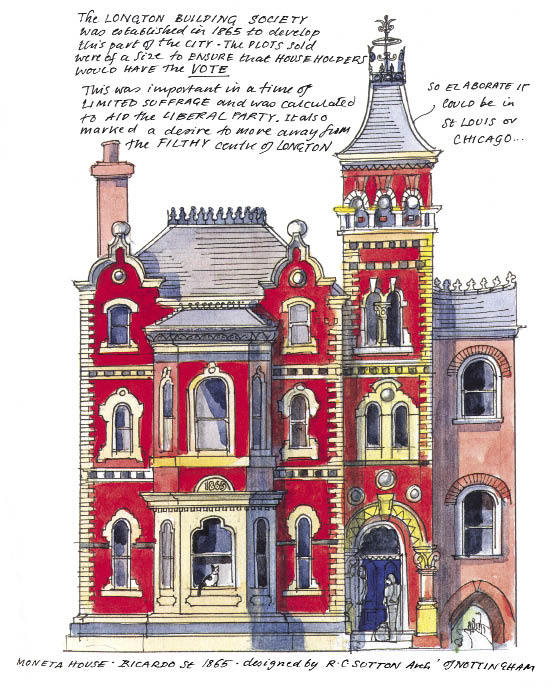

Yet for all that, this generously illustrated book makes you long to revisit this bizarre wonderland of post-industrial dereliction. His sketches and drawings of streets and buildings, of ceramics and pot banks and tiles, of cornices and columns and string courses and pediments, take you on a journey through the six towns (misleadingly but immortally lumped together as the Five Towns by their muse, Arnold Bennett) and reveal the survivals and failures of this sprawling, haphazard conurbation. He gives us a little history, a little fantasy, a little whimsy, and a fair amount of wrath directed at town planners and wanton demolition, at the terrifying A500 and at recent ‘insensitive and insulting’ commercial designs. But the overall effect is exhilarating. He makes even the most down-at-heel terraces look full of architectural interest.

In an early section of Bennett’s Clayhanger, this year marking its centenary, the young Edwin is introduced to the concept of the unacknowledged beauties of Burslem by his friend’s father, the architect Mr Orgreave, who points out to him with admiration the Georgian façade of the Sytch Pottery. Matthew Rice, like Mr Orgreave, does a good job of revealing what we might otherwise overlook, pointing out the boot-scrapers of the artisan housing and the elegant iron balconies of Waterloo Road where the Clayhangers built their fine new home.

Rice’s tastes are eclectic, and a characteristic comment on a sketch of the porch of an 1865 villa in Ricardo Street in Longton notes that it is ‘absurdly grandiose, of dubious architectural parentage, and splendid’. And there is a fine drawing of Webberley’s Bookshop, late Victorian, which, when I last visited it, had a range of stock that would put most other high street bookstores to shame.

Rice peoples his townscapes with little figures — postmen, shoppers, youths smoking cigarettes. Some are from the glorious past, like Denry and the Countess of Chell from Bennett’s The Card, in evening dress and about to enter Burslem’s famous angel-crowned Town Hall. Representing the present are two ‘depressed culture lovers’, standing in front of the startling polychrome Wedgwood Institute, perhaps deploring its poor state of repair.

The six towns, for historic reasons of rivalry, have too many municipal buildings, some of which now stand unused. They also have an excess of places of worship, ranging from the ‘wonderfully idiosyncratic’ St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church in Burslem to the Bethesda Chapel in Hanley, from the commissioner’s Gothic of Stoke Minster to the 1860 Methodist Church in Old Town Road, Hanley, which became a spiritualist church in 1926 and, in 2005, a restaurant. One of Rice’s boldest suggestions is that the growing Muslim population could turn some of the empty churches into mosques —

The closing section of the book outlines what Rice and his wife, the potter Emma Bridgewater, are contributing to the future. In 1994 they bought the vast Eastwood Works in Hanley, where 200 people now work. The façade is as long as that of Chatsworth, and the Lichfield Street rooms of the factory are twice as long as the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. This is a brave enterprise.

So the lost city is not quite lost. Nor is Arnold Bennett as forgotten as some journalists claim. He is often invoked by Rice, and this month a volume of his lost and uncollected stories is published by Churnet Valley Books of Leek. He, like the Potteries he revealed to us, lives on, and repays exploration.

Comments