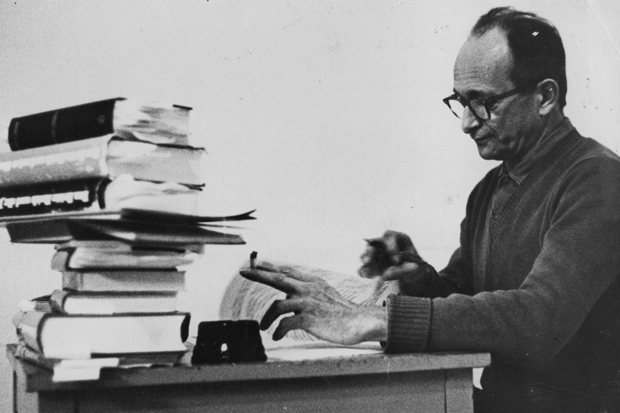

Over Christmas I finally got around to reading Eichmann Before Jerusalem by Bettina Stangneth. I cannot recommend this book – newly translated from the German – highly enough. It challenges and indeed changes nearly all received wisdom about the leading figure behind the genocide of European Jews during World War II.

The title of course refers to Hannah Arendt’s omnipresent and over-praised account of Adolf Eichmann’s 1961 trial, Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil. I would say that Stangneth’s book not merely surpasses but actually buries Arendt’s account. Not least in showing how Arendt was fooled by Eichmann’s role-play in the dock in Jerusalem. For whereas Arendt famously portrayed the man in the glass booth as a type of bureaucrat, Stangneth shows not only that Eichmann was not the man Arendt took him to be, but that she fell for a very carefully curated and prepared performance. Putting together a whole library of scattered documents from Eichmann’s exile in Argentina in the 1950s, Stangneth puts the actual, unrepentant Eichmann back centre stage.

There are a number of startling discoveries in the book, not least among them being the extent to which Eichmann had kept up with the books and scholarship on the Holocaust as they came out so that by the time he was awaiting trial in Jerusalem he was fully on top of all primary and secondary material put to him. There is also the extent to which Stangneth is able to show (through accounts from various members of the South America Nazi circles) how well known the true identity of ‘Ricardo Klement’ actually was within the German expat community in those years.

But Stangneth’s principle scholarly triumph has been her ability to piece together and make sense of the extant transcripts and recordings known as the Sassen conversations. Together with Eichmann’s contemporary attempts at memoir-writing they bring a wholly new interpretation on his years in Argentina. These conversations – recorded by the journalist and Nazi Willem Sassen in the 1950s – came to light before Eichmann went on trial. But in Jerusalem Eichmann threw doubt on their authenticity and for this reason (as well as the complex dissemination and distribution of the transcripts plus disputes over ownership as well as attempts to disown them) the complete picture of these interviews has taken until now to come to light. Stangneth’s work on these materials is extraordinary and the results more than reward her considerable efforts. For instance she shows that those who participated in the conversations (including Sassen himself) tried very hard to cover over exactly what had gone on after Eichmann was abducted by the Mossad. And Stangneth startlingly shows the extent to which these discussions were far from being one-on-one interviews but were in fact semi-public events.

The nature of these events, and their content, is of considerable contemporary as well as historical relevance. For two reasons in particular. The first relates to the ongoing European discussion of free speech and Holocaust denial laws. Because Stangneth shows that as an increasing amount of information on the Holocaust came to light in the 1950s the immediate reaction of the remaining Nazis and neo-Nazis in South America was denial. Some of the Argentina Nazis sincerely believed that the Federal German Republic would not last and that their belief system might yet return to save the German people. But even these remote fantasists realised that the news of the Holocaust presented problems for their rehabilitation. And so they hoped to expose the Holocaust. Their first attempts were not only crude but were swiftly overtaken by an unstoppable flood of information and scholarship. By the mid-1950s even the most committed remaining Nazis clearly found ignoring the weight of evidence to be an uphill struggle. And so this group of Nazis in South America, brought together by Sassen, thought that Eichmann might provide the solution to their quandary. They believed that Eichmann would be able to help them not just because he had been the person most closely involved in the Nazi programmes against the Jews, but as the man cited at Nuremberg as having first used the six million figure. The Buenos Aires Nazis assumed that if they got Eichmann on record then they could show the world that the six million figure was a lie, or at least a great exaggeration.

By this point Eichmann was also thinking of breaking his cover in some way. In 1956 he once again attempted to write a book, this time provisionally titled Die anderen sprachen, jetzt will ich sprechen [The Others Spoke, Now I Want to Speak!]. But the conversations with the Sassen circle – which came from the same instinct of his to break his silence – turned out to constitute an attempt to square an impossible circle. For Eichmann saw the Sassen circle’s efforts to minimize the Holocaust as something like a spitting on his life’s work. Eichmann knew that the six million figure was accurate, and seems to have only gradually realised that his audience were hoping for something quite different from him. The discussions clearly broke down under this unresolvable issue. Among the reasons why I would suggest that this has some contemporary relevance is that it is the clearest possible reminder of how in open discussion even the people most committed to trying to prove the Holocaust did not occur (former leading Nazi officials) ended up being unable to disprove the facts. On that occasion – as so often – they slunk away.

But the second reason why Stangneth’s book seems relevant for more than historical reasons is because of what it tells us about a stream of poison which remains very much at the centre of current events.

In The Others Spoke, Now I Want to Speak! (the reference is to his former colleagues who – in another un-square-able moment – Eichmann believed had defamed him at Nuremberg) he had the opportunity to write about the recent Suez Crisis. Here is one passage Stangneth quotes which was new to me at least.

‘And while we are considering all this – we, who are still searching for clarity on whether (and if yes, how far) we assisted in what were in fact damnable events during the war – current events knock us down and take our breath away. For Israeli bayonets are now overrunning the Egyptian people, who have been startled from their peaceful sleep. Israeli tanks and armored cars are tearing through Sinai, firing and burning, and Israeli air squadrons are bombing peaceful Egyptian villages and towns. For the second time since 1945, they are invading… Who are the aggressors here? Who are the war criminals? The victims are Egyptians, Arabs, Mohammedans. Amon and Allah, I fear that, following what was exercised on the Germans in 1945, Your Egyptian people will have to do penance, to all the people of Israel, to the main aggressor and perpetrator against humanity in the Middle East, to those responsible for the murdered Muslims, as I said, Your Egyptian people will have to do penance for having the temerity to want to live on their ancestral soil… We all know the reasons why, beginning in the Middle Ages and from then on in an unbroken sequence, a lasting discord arose between the Jews and their host nation, Germany.’

There then follows an extraordinary and important passage. For Eichmann goes on to say that if he himself were ever found guilty of any crime it would only be ‘for political reasons’. He tries to argue that a guilty verdict against him would be ‘an impossibility in international law’ but goes on to say that he could never obtain justice ‘in the so-called Western culture.’ The reason for this is obvious enough: because in the Christian Bible ‘to which a large part of Western thought clings, it is expressly established that everything sacred came from the Jews.’ Western culture has, for Eichmann, been irrevocably Judaised. And so Eichmann looks to a different group, to the ‘large circle of friends, many millions of people’ to whom this manuscript is aimed:

‘But you, you 360 million Mohammedans, to whom I have had a strong inner connection since the days of my association with your Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, you, who have a greater truth in the surahs of your Koran, I call upon you to pass judgment on me. You children of Allah have known the Jews longer and better than the West has. Your noble Muftis and scholars of law may sit in judgement upon me and, at least in a symbolic way, give me your verdict.’ [pp 227-8]

Elsewhere Stangneth shows how open Eichmann must have been in his admiration for Israel’s neighbours. After Eichmann’s abduction his family apparently became concerned about his second son. According to a police report, ‘As Horst was easily excitable the Eichmann family was afraid that when he heard about his father’s fate, he might volunteer to fight for the Arab countries in campaigns against Israel.’ As Stangneth adds, ‘Eichmann had obviously told his children where his new troops were to be found.’ [229]

Of course for years after the war there were rumours that Eichmann had fled to an Arab country. He might have had a better time there. Other Nazis certainly did, including Alois Brunner – Eichmann’s ‘best man’ – who settled in Damascus after the war and who is now believed to have died in Syria as recently as 2010. Eichmann’s Argentina years were certainly filled with frustration and rage. What is most interesting is how mentally caught he remained even before he was captured, principally by the impossible conundrum of how to persuade the world to accept what he had done and simultaneously boast about his role in the worst genocide in history.

There is much more to say about this book. But I do urge people to read it. Not least for the way in which Stangneth sums up the problem with the only strain of Nazi history which really remains strong to this day. ‘Eichmann refused to do penance and longed for applause. But first and foremost, of course, he hoped his “Arab friends” would continue his battle against the Jews who were always the “principal war criminals” and “principal aggressors.” He hadn’t managed to complete his task of “total annihilation,” but the Muslims could still complete it for him.’

Comments