Sam Leith on Tony Judt’s rigorous, posthumously published examination of the great intellectual debates of the last century

When the historian and essayist Tony Judt died in 2010 of motor neurone disease, among the books he had planned was an intellectual history of 20th-century social thought. As the disease robbed him of the ability to write, his friend Timothy Snyder proposed making this book — out of the edited transcripts of a long conversation they would conduct over several weeks in 2009.

The book-as-conversation is, as Snyder points out in his foreword, a rather Eastern-European artefact. That’s apt to its content: Snyder is a historian of the region. Judt has his Jewish family roots there, and became deeply interested during his mid career in the under-explored complexities of the Eastern European 20th century. Among the thrilling things about Judt — who worked in Cambridge, Paris, Berkeley and New York — is his lack of parochialism.

This is, as you might expect from the method by which it came about, a digressive rather than a systematic look at the subject. It’s also a slantwise autobiography. If the book Judt intended would have resembled a map of the intellectual landscape of the 20th century, this is something different. It’s more of a stroll through that landscape in the company of a pair of ghillies who know it intimately; and one of whom doesn’t mind reminiscing about his own youth among the hills and crags.

There’s chewy stuff here, but you never have to read a sentence twice. I underlined very many of them. Judt had in abundance the virtues of scepticism, open-mindedness, the ability to pay sustained attention to and across several fields of study, a tolerance of complexity and (how I envy him the last above all) the skill of remembering in clear detail what he has read.

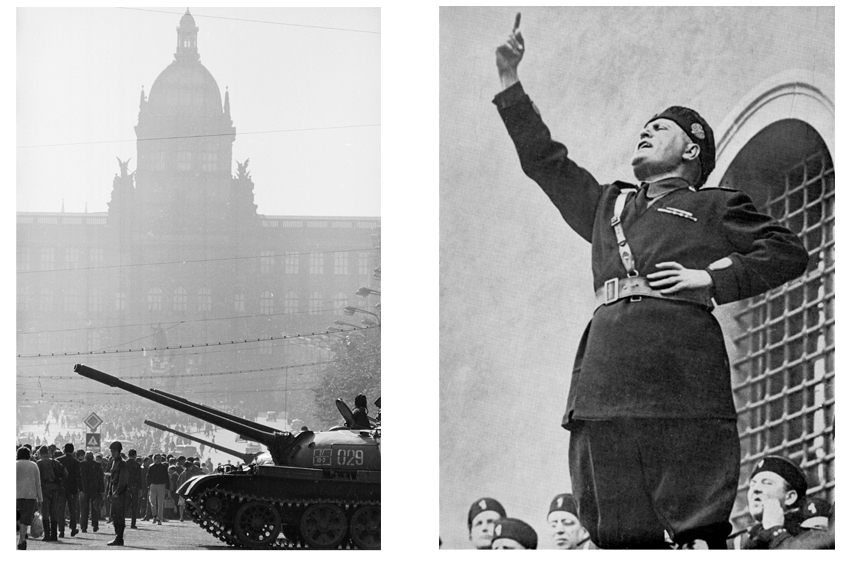

Thinking the Twentieth Century falls into two parts, roughly. The first meanders through the intellectual history of the century — with special attention to the left (he finds, in Fascist thought, nothing to think) and to the mid-century confrontation between totalitarianisms. The second pulls focus to a more general consideration of the role of the intellectual in public life, the case for social democracy, and the question of what historians should do. It fades into a wanly pessimistic consideration that, after the utopianisms of the last era, ‘We are likely to find ourselves as intellectuals or political philosophers facing a situation in which our chief task is not to imagine better worlds but rather to think how to prevent worse ones’ (an echo of what he calls the ‘republicanism of fear’ in Hannah Arendt).

Judt’s approach to history, to the history of ideas and to ‘the history of historiography’, is one that insists on an engaged as well as a contextualised understanding. He’s a moralist and — in his attitude to the ‘cesspit of Theory’ — he’s a materialist. But he’s also alive to the aesthetics and psychology of political positions. He discerns something similar — nostalgia for a world lost — in Keynes’s economics and Stefan Zweig’s fiction, for instance, and identifies the appeal to Britons of Italian Fascism — ‘not so much a doctrine as a symptomatic political style’ — as its being ‘everything that they missed in the tired, nostalgic, grey world of Little England’.

Along with its rigour and perceptiveness, this book has that casually aphoristic quality of really smart table-talk. ‘[G. E.] Moore, it seems fair to say, is what Nietzsche would have looked like had he been born in England.’ ‘Stalin’s destruction of the Soviet intelligentsia was piecemeal. And essentially retail. Mao murdered wholesale; Pol Pot was universal.’ ‘It was Leszek Kowalski […] who famously observed around that time that reforming socialism was like frying snowballs.’

The rush of warm public feeling towards Judt as his end approached — his canonisation as a sort of mascot of the social-democratic left — could lead you to think of him as cuddly. He wasn’t. He was intellectually cussed, positively relished a fight, and had an ego on him. This is a book with spikes and prickles, and is the livelier for it.

When Judt identifies a fellow historian as a descendent of Carlyle, Macaulay and Michelet, he doesn’t mean it entirely as a compliment:

Even the romantics have their contemporary heirs: the bombastic, syntactically incontinent quality of their writing is effortlessly and serially reproduced by Simon Schama in our own time. And why not? It’s a style for which I do not care; but many people love it and it has a classical pedigree.

Others fare less well. Hayek is dismissed for his ‘political autism […] manifest in that inability to distinguish the different politics that he didn’t like from one another’. E. P. Thomson is described as ‘the prominent English left-wing historian and publicist’.

There’s a not altogether attractive vein of cattiness about his ex-wives, too. One of them, he grumbles, ‘seemed never to be satisfied where she was’ and dragged him to an inconvenient berth in California, necessitating a long and resented commute. Another got hacked off by Tony’s trilingual conversations with Polish intellectuals:

Patricia, who could not sustain such exchanges and who deeply resented her implicit exclusion, wanted nothing so much as to go home, read Newsweek in bed and chew pumpkin seeds.

Judt, temperamentally and intellectually, was a sort of insider outsider: a lapsed Zionist who became a fierce critic of Israeli exceptionalism; a man marinated in Marxist thought (his dad gave him a three-volume biography of Trotsky for his 13th birthday) who rejected the Marxisms on offer; a tenured academic with a magnificent scorn for Anglo-Saxon academic careerism. In Paris: ‘I was on the career path of an English historian, but thought of myself as a dissenting French intellectual and acted accordingly.’

Of university life in England he says:

To become an insider at Cambridge or Oxford does not in itself require conformity except perhaps to intellectual fashion; it was and is a function of a certain capacity for intellectual assimilation. It entails knowing how to ‘be’ an Oxbridge don; understanding intuitively how to conduct an English conversation that is never too aggressively political; knowing how to modulate moral seriousness, political engagement and ethical rigidity through the application of irony and wit, and a precisely-calibrated appearance of insouciance.

That said, he does sometimes sound a little high-table himself when it comes to the common herd: ‘the tendency of mass democracy to produce mediocre politicians is what worries me’; ‘the vast majority of human beings today are simply not competent to protect their own interests’. He’s only half-joking, I think, and he’s clear about the remedy: make the people less stupid.

Judt evinces a Gove-pleasing determination that coherent narrative and factual accuracy are the bedrock of any historian’s job — and that teaching relativist ‘progressive history’ betrays a vital duty to civic society: ‘A scholar of the past who is not interested in the first instance in getting the story right may be many virtuous things but a historian is not among them.’

Interrogating the occluded voice of the Anglo-Saxon subaltern, in other words, comes second: knowing who won the Battle of Hastings comes first. Many Spectator readers will be out of sympathy with Judt’s views on just about everything. But on that, I think, we can all agree.

Comments