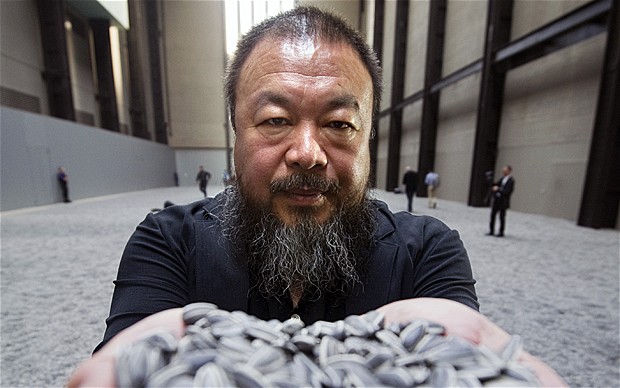

In September, the Royal Academy of Arts will present a solo exhibition of works by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. This follows his installation of porcelain sunflower seeds in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, a solo show at Blenheim Palace and two solo exhibitions at the Lisson Gallery (which represents him). Peculiarly, the Royal Academy’s press release claims that Ai’s work has not been seen extensively in Britain, which might suggest that its press team doesn’t get out much. He has certainly been exhibited here more than other key Chinese contemporary artists such as Zeng Fanzhi, Yang Fudong or Gu Wenda.

Ai transcends the art world, particularly since his arrest by the Chinese authorities in April 2011 when he was held without charge for 81 days. His detention sparked petitions, protests, a Free Ai Weiwei website and an Anish Kapoor-led lip-syncing video of the South Korean pop hit ‘Gangnam Style’ featuring prominent art-world figures. Mysteriously, the Chinese authorities failed to bow to pressure from the staff of MoMA, Norman Rosenthal and the Serpentine Gallery team dancing in the style of a jaunty horse-rider. A few months after his arrest, Ai was named as the most powerful person in Art Review’s Power 100 (he’s since drifted down to number 15, although that is still above Gerhard Richter, Jay Jopling and François Pinault).

Behind the adulation, however, there is a growing feeling that the actual artwork Ai produces is simply not up to much. In 2013 there were a couple of significant take-downs of his work. The first was an in-depth essay by the art critic Jed Perl. While making clear his admiration for Ai’s stand against the Chinese authorities, Perl argued that his art was alternately inane or derivative of American modernism. The early work is described as ‘highly diluted Dadaism’ and the later work as ‘postmodern minimalist political kitsch, albeit in the name of a just cause’. A more withering assessment came from Francesco Bonami, one of the art world’s most well-respected and plainly spoken curators. ‘I hate Ai Weiwei,’ Bonami said in an interview. ‘I think he should be put in jail for his art, and not for his dissidence …I think he exploits his dissidence in favour of promoting his art.’ Bonami’s critique was fleshed out by Colin Chinnery in a review for Frieze in September 2014. Like Perl, Chinnery noted his respect for Ai’s political stance but argued that the artist had moved from focusing on China’s political issues to a relentlessl focus on himself.

Lurking beneath this is the suspicion that Ai’s valorisation by large sections of the western art world is shot through with a certain level of cultural condescension. Of all the well-known Chinese contemporary artists, Ai’s work is the most attuned to western modern art movements. He uses the now rather obvious Duchampian strategy of treating everything as a readymade and Chinese cultural artefacts are often recontextualised in his work in this way. He is an ideal Asian artist for lazy western curators, making works that signal their ‘Chinese-ness’ through him waving around Chinese objects such as Han vases, while saying appropriately negative things about the Chinese authorities. Bonami went a bit far. Ai Weiwei doesn’t deserve prison for his art, but on the other hand he probably doesn’t deserve the whole of the Royal Academy.

Comments