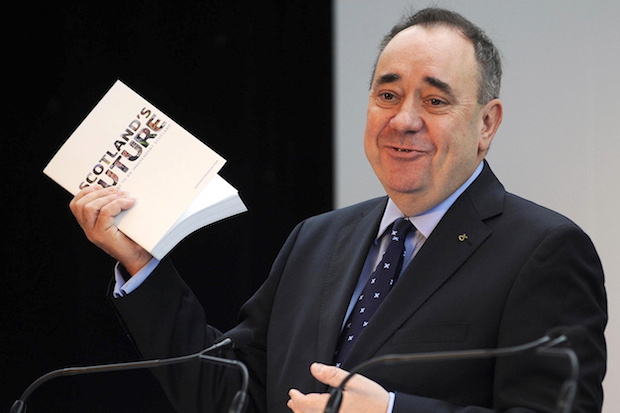

As I type this, Alex Salmond and Mark Carney are chowing over porridge at Bute House, the First Minister’s official residence in Edinburgh. There is always the risk of exaggerating the importance of these things but this morning’s meeting with the Governor of the Bank of England may be the most important encounter Alex Salmond has this year.

The question is simple: will an independent Scotland be able to forge a currency union with the rump United Kingdom? The answers, for all the First Minister’s bland assurances that such a union is in everyone’s interests, are not so simple. Like poker players, politicians often have a “tell”. When Salmond offers a kind of breezy emollience he’s often holding weaker cards than he wants you to think.

When a Come now, old boy, why don’t we be sensible and just work this out? tone is lacquered on top you know the First Minister is really making a bet he’s no desire to see called.

Politics and economics are uneasy companions at the best of times. It is not always clear who is supposed to be serving who. In the case of the SNP’s hopes of retaining sterling we may safely say that economics must be bent to aid politics.

The pound sterling, after all, is the party’s third different preferred policy in 30 years. True, other parties have changed their minds on the euro but no other British political party has been as promiscuous as the SNP in these matters.

First there was the Scottish pound, proud symbol of an independent Scotland. Then there was the euro, cheerful guarantor of international credibility and symbol of pan-european solidarity. Now we are back to where, actually, we are today: the pound sterling, the common sense arrangement that is in everyone’s best interests. That includes you, England, because of the balance of payments and oil and whisky and all that stuff.

None of these are terribly attractive options. An independent Scottish pound with interest rates and so on set by an independent Scottish Central Bank at least has the merit of clarity. It’s what other, normal, countries have done. But you can see how it would play in the press: what about the uncertainty First Minister? Business might complain too about the costs of currency exchange in doing business with our largest trading partner. It might, the Scottish pound, be a nice idea but it just wouldn’t work. Too much of a whiff of Jacobite fancy, you know.

So the euro. Independence in Europe was the phrase coined by big Jim Sillars in, if memory serves, 1989. It was certainly a better slogan than Free by 93. Independence in europe. Who could be against that? Could anything contain two better things than independence and europe? Hardly. The best of all possible worlds: independence and safety.

And that was tenable until the eurozone blew up. True, the continent’s crisis has, at least for now, abated (another triumph of politics over economics) but in Scotland, as in England and Wales, the euro is tainted goods and not even Mr Salmond can salvage anything from that. So times change and I change mind too, says th eFirst Minister. You have a problem with that?

Not really. Except for this: the problems of a currency union within the United Kingdom are the same, albeit on a smaller scale, as the problems of a currency union across the european union. Indeed, noting the inadequacies of sterling – and especially the management of sterling – was for a long time a key part of orthodox SNP thinking. It was Alex Salmond who described sterling as an anchor and he didn’t mean by that the idea sterling kept Scotland safe. Rather the reverse in fact.

Awkwardly, the only way to explain this volte face is for Salmond to admit that he was twice wrong back then. Wrong to think of sterling as an anchor dragging Scotland down and wrong to think the euro offered a safe harbour. You can get away with admitting some mistakes; admitting so many on a single question begins to look like something worse than carelessness.

A sterling union it is, with the Bank of England setting Scottish monetary policy and acting as lender of last reserve to Scottish banks. If this seems sub-optimal it may be that, for political rather than economic reasons, all the options available to Salmond are sub-optimal.

Be that as it may, there are other difficulties too. Keeping the pound subtly undermines the entire idea of independence. Sure, it’s an interdependent world and all that but you can take these things just a wee bit too far.

Moreover – and this is a ticklish problem – the First Minister is writing a cheque he cannot honour. Nor, for that matter, can Mark Carney. A currency union of the sort favoured by the First Minister will have to be approved by the Westminster parliament. The very parliament Salmond says cares not a fig for Scottish interests. His whole career has been predicated upon that notion. Now, however, Westminster will see the light and do the decent thing.

Because, of course, it is in Westminster’s own interests to do so. Here again, however, the SNP display a touching faith in the notion that the British state, so hopelessly unreformable and sclerotic in so many other areas, will see the light and act in its own national interest. Even though Salmond thinks British policy misguided and counter-productive most of the time and in most areas. If he’s right about that, why does he think parliament will suddenly see sense and agree with him on this?

Isn’t all this a collection of technicalities that, in terms of the debate, have no impact upon the pound in your pocket? Up to a point. Project Reassurance can go too far. If a continuing currency union is the common sense solution and if, by the Scottish government’s own estimation, something like 30% of existing cross-border entities will remain intact after independence is it not just possible that the common sense solution lies in maintaining the Union too? It would certainly seem simpler.

Perhaps that is not the case but it is rather where the logic of Salmond’s own position and current preferences leads. A currency union might be the best available option but it is a tactical approach that subtly undermines the SNP’s wider strategic interest. It does not smack of confidence, rather it suggests a certain fear that the Scottish people might not actually be up for the kind of change in which the SNP would like them to believe.

Comments