Back home from a week in Italy, I almost feel that I haven’t left. For I go almost at once to Milton Keynes to see Donizetti’s quintessentially Italian opera, L’elisir d’amore. It is a superb, joyous production by the Glyndebourne Tour company, one of which any great international opera house would have been proud. And here it is being performed in Milton Keynes, not a town generally associated with cultural sophistication. But then ‘Das Land ohne Musik’, as England was once cruelly called by a German music scholar, is now awash with opera. It has been spread across the land by country opera festivals, springing up everywhere in imitation of Glyndebourne, and by opera touring companies penetrating even the least-favoured parts of the country (among which I don’t, of course, include the booming city of Milton Keynes). And thanks to Benjamin Britten, whose centenary is being celebrated this year, they even put on operas that are actually English.

This year I have been to more operas than I have for ages. I saw Wagner’s Ring at Longborough in Gloucestershire, his Parsifal at the Proms, and Britten’s Peter Grimes on the beach at Aldeburgh in Suffolk. I also saw a stunning performance of Richard Strauss’s Elektra at the Royal Opera House. And then to make up for the greater attention paid to Wagner than to Verdi in their joint bicentenary year, I went to four Verdi operas at the ROH: Rigoletto, Otello, Simon Boccanegra, and Les Vêpres Siciliennes. I am left feeling rather amazed by the high quality of almost all these performances. If England could once be dismissed as a country without music, it hardly can be any more.

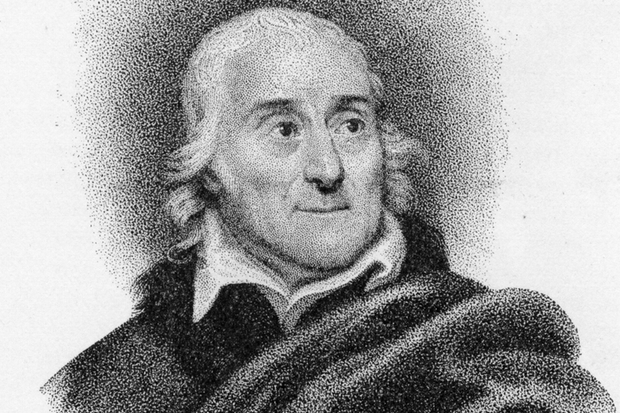

In Italy I read Anthony Holden’s biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, the Italian poet and author of 28 opera libretti, whose life was so weird and chaotic as to be hardly believable. Born in 1749 into a Jewish family in the town of Ceneda in the republic of Venice, he died in New York 89 years later. In the meantime he had been converted to Catholicism, become a priest so dissolute (in the manner of his friend Casanova) that he was banned from Venice, moved to Vienna where his gifts as a poet and librettist earned him the patronage of the Habsburg emperor Joseph II, met Mozart and written the libretti for his three most famous Italian operas (The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte), lost all his money, married a beautiful English girl to whom, unexpectedly, he remained for ever faithful, moved to London, worked for the Italian opera theatre (now Her Majesty’s Theatre) there, but eventually fled bankrupt with his family to New York, where he ended up as professor of Italian literature at Columbia University and became an American citizen.

To make a living in America, Da Ponte was reduced at times to running a grocery store in addition to teaching Italian and Latin to American students and supplying his university with Italian books; but his great mission was to introduce Italian opera to his adopted country. When efforts met at first with little success, he blamed this on New York’s lack of a proper opera house, so he decided to build one, the first in the country: and amazingly, in his mid-80s, he managed to raise the funds to do this in the area now known as TriBeCa. It was a very grand opera house in the European style, but it lost money and after two seasons was sold to a theatre company, only to be burnt down shortly afterwards. Da Ponte died in 1838 and was buried in an unmarked grave; but nearly 200 years later, his hopes have been triumphantly met.

The United States, like Britain, is now opera-crazy; and a survey carried out by the magazine Opera America shows that between 1995 and 2012 the five most-performed operas in American theatres were Italian. Top came Puccini’s La Bohème with 229 different productions, second Verdi’s La Traviata with 196 productions, and third Mozart and Da Ponte’s The Marriage of Figaro with 164. Immediately below it came Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (112), which had its first performance in Naples in 1835, just a year after Da Ponte’s new opera house held its first season in New York. And eighth on the list of the ten most performed operas in the United States, just after Bizet’s Carmen and Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, came, rather surprisingly, an English opera. It was, with 162 performances in 55 different productions, Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado.

Comments