There was a time when sportsmen fretted about the morality of being paid to play. Now the question is whether you are taking money to win, or taking money to lose. Mervyn Westfield, the Essex fast bowler, was only 20 when he accepted £6,000 to bowl deliberately badly in a county match. Three Pakistani cricketers, of course, are in prison for the same offence. How quaint the old distinction between the amateur who plays for love and the pro who toils to make ends meet now appears.

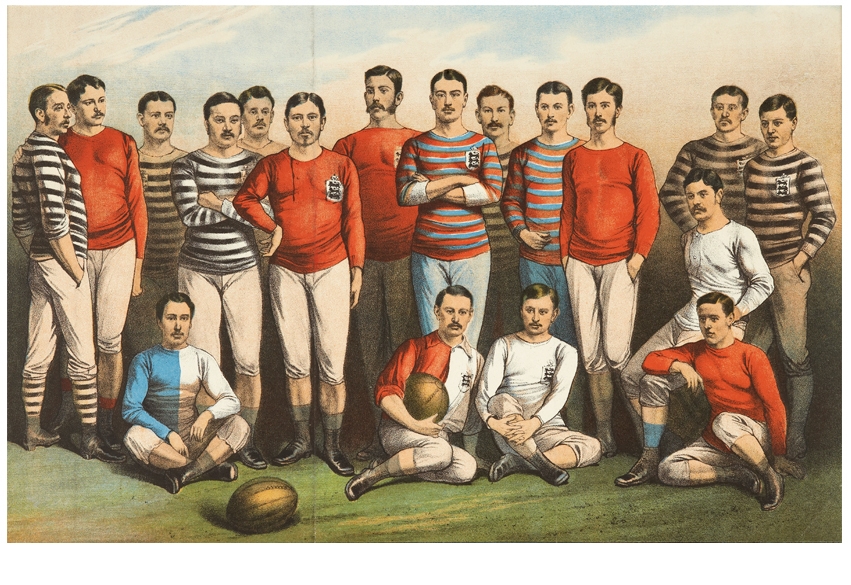

How did sport become so morally complicated? It was the Victorians, as Mihir Bose explores in The Spirit of the Game, who decided that sport had to be good for you. The Georgians, in contrast, had been content with sport’s more obvious pleasures of gambling, blood-letting and licentiousness. The Victorians, with an empire to run, wanted sport to educate the officer class. No matter that Thomas Arnold, allegedly the founder of ‘muscular Christianity’, didn’t even like organised games. With Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the idea that Britain became great by playing sport hardened into folklore.

Baron de Coubertin added a few embellishments of his own, cementing the idea that sport was a vital part of a healthy education. Sport’s advocates, as Bose puts it, ‘had spelt out the purpose of games long before most sports had drawn up their rule or codes of conduct. Sport had acquired a philosophy before it had been properly organised.’ The legacy of that tension — between the idea of sport as a moral enterprise, and the reality of sport as a pastime and increasingly a business — is still evident today.

Bose, once BBC sports editor, has spent his life in the corridors of sporting power, and his book is strongest when he is an eye-witness rather than just a chronicler. The sparkling chapter on apartheid in South Africa describes how Bose and a distinguished group of cricketers met Nelson Mandela at his home in Soweto in 1991.

Bose stresses the complicity of other sporting powers. South Africa not only declined to select their own talented black players; they also refused to play against blacks from other countries. Before their 1949 tour of South Africa, the New Zealand Rugby Union announced that ‘much as it is regretted, players to be selected to tour South Africa cannot be other than wholly European.’

There was a long, shameful record of cravenness before the Basil D’Oliveira affair in 1968 precipitated South Africa being frozen out of international sport.

Bose ends his book with a familiar call to arms. Sport, he argues, has become highly professional on the pitch, but remains distinctly amateurish off it. The global sports market is estimated to be worth around £500 billion a year — which surely demands professional administration and proper corporate governance.

Bose draws unflattering comparisons between the European scene and the slickly commercialised American sports. But I am less convinced that copying the American model would work elsewhere. American sports are inextricably bound up with national identity, and bankrolled by the richest and most patriotic sporting market in the world. They are so deeply entrenched in American consciousness that they don’t have to be especially well run to survive.

The book’s subtitle is ‘How Sport Made the Modern World’, as though sport has not merely reflected history, but actively shaped it. It is an interesting idea, demanding a Niall Ferguson-style combination of tightly argued polemic and grand, over-arching narrative. The Spirit of the Game is not that book. It is wonderfully rich in historical detail and anecdote — quotations make up a good portion of it — but the argument is left somewhat to emerge of its own accord. Bose’s achievement is different. He has crunched almost the whole history of organised sport into 500 densely packed pages. I cannot think of a more exhaustive book on modern sport.

It is quite a journey from Tom Brown to the London 2012 Olympics. For all its problems, sport brings happiness to more people around the world than ever before. How funny to think that hardened newspapermen used to refer to the sports pages as the toy department, as though sport wasn’t quite real. That was before the rest of the ‘serious’ news cycle was so influenced by spin and gossip. At least the toyshop is anchored in events that cannot be rewritten: when we read that Arsenal beat Leeds 1-0, at least we know that is what actually happened.

That is the paradox: sport is both a playful release from serious life and yet also reassuringly real. And while the spirit of the game may be threatened, the place of sport in our lives is looking more secure than ever.

Comments