Of those prime ministers whom the old grammar schools escalator propelled from the bottom to the top of British society since the second world war, Ted Heath and Margaret Thatcher were in many ways the most alike. Wilson, that classic greasy-pole climber, tactically brilliant, strategically trivial; Major, decent, straightforward, a good man lifted to power on the shoulders of his many friends as a healer who could unite: both these are types, the one less admirable than the other, but familiar to history. Heath and Thatcher are much odder, more dangerous and more remarkable. It is an extraordinary tribute to the modern Conservative Party that both chose it as the instrument through which to try to deliver their radical visions — as it is to the party that it chose them. In return, both nearly broke the party while doing what they believed they had to do.

It is impossible to read Philip Ziegler’s brilliant and timely book without renewed astonishment at the energy and scale of the change Heath wanted. From his earliest days, child of what he would always describe as a working-class family, he saw himself (as did his mother) as destined to be an instrument of history. The direction in which he wanted to move that history had astonishingly consistent principles from the start. Hatred of class; belief that every problem had a rational solution and that he could find it; contempt for what he saw as the incompetence and staleness of much of the way in which Britain was run, especially British industry; fear that the energy and scale of the US and other continental powers would leave a fragmented Europe on the sidelines — all this is there in the boy and the young Balliol organ scholar. We await Charles Moore on Thatcher, but I shall be astonished if there are not similar drivers in that story too.

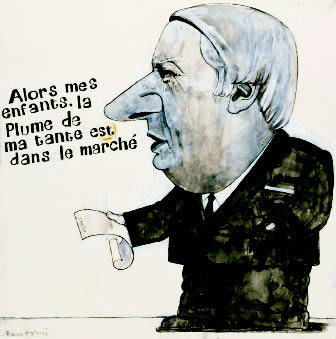

Heath on his way to high office scarcely puts a foot wrong: right on appeasement; right on Spain (without making the ludicrous error of falling for the Communists); an extremely successful soldier, commanding men in action with efficiency and courage and winning not just their respect but their affection; an assistant Whip whom everyone likes and trusts; a liberal and moderniser on hanging, the rights of women, devolution and aid to the third world, but not strident or priggish. All this allied to an astonishing capacity for detailed hard work and an unchallenged integrity, and the Heath who emerges in the early Sixties really does seem the destined midwife of a new, modernised, post-imperial Britain, matching Adenauer, Erhard and de Gaulle across the channel. That is, though nervously, what the Conservatives thought they had found.

When, to the astonishment of the pollsters and political commentators, but not for a moment to his own, he won the 1970 election, confirming in his own mind the feebleness of all those who doubted, and the soundness of the British people’s judgment, the range and pace of the change he sought was phenomenal.

This was the heyday of a certain quite coherent theory, developed by political historians and thoughtful journalists, of how Britain had organised itself to win the war — a war for Heath as much as for anyone of his age the formative experience of his life. The theory was that victory had derived from a new social contract between leaders and led: after the war, a fairer society would reward the titanic sacrifices made by a nation which had stood together. Samuel H. Beer’s British Politics in the Collectivist Age gave the most famous academic account of this: the language of social contract suffused Macmillan’s and Heath’s conservatism. There would be no more mass unemployment as an instrument of economic control. Keynes, after all, had invented techniques of demand management that would mean government could deliver full employment; collective discussions orchestrated by government between labour, capital and consumers would achieve consensus around a framework in which free enterprise could deliver the goods, as seemed to have happened in Germany, France and Japan.

That was the background. The policies, set out at Selsdon Park before 1970, were never meant to represent a return to laissez faire, still dirty words then in mainstream British politics. No one doubted that unions, industry and government could and should act in partnership. Conservatives, after all, had fought 19th-century economic liberalism; we believed in a powerful State as well as free enterprise. American right-wing state minimalism had as little to do with British Conservatism as did European Catholic-based right-wing statism.

The economy rationally managed; Europe as the modernising catalyst (the Treaty of Rome embodying as it did commitment to free enterprise); British industry revitalised by European competition and Europe (with Britain) returned to the centre of the world stage as equal partners with the US; a rational reform of trades union law; huge capital investment in new projects like the Channel Tunnel; a fair solution to the problems of Northern Ireland; class barriers and prejudice swept away. All this and more was to be done, and quickly (as well as dealing with the usual menu of unforeseen crises). The model was how Heath had swept away Resale Price Maintenance in the dying days of Douglas-Home’s government, confounding reactionaries and lobby groups. The proof that his style of leadership worked was the election victory itself. Doubtful back-benchers would be won over by success, not by back-slapping in the team room, and the nation rebuilt not by Wilsonian debating tricks but by doing the right thing.

And it quite nearly worked. It is extraordinary how much the government of 1970 took on in those three and a half years. An enormous programme of fundamental change was indeed launched — much of it to be undone in the defeatist and sleazy years of the second Wilson government. Easy to say now that tripartite economic management and the trades union laws were doomed to fail: but moderate trades unionists as well as good industrialists did not think it inevitable then. Sunningdale got within a whisker of power sharing in Northern Ireland 20 years before Major and Blair delivered it. We did get into Europe and start tentatively behaving like the Gaullists Heath often envied; we did for the first and last time since Churchill sometimes stand up to the Americans. Britain did for a brief moment seem to be on the move.

But of course it all went wrong. Some policies were inherently bad: a far too expansionary fiscal policy allied to a world commodity boom was bound to drive prices and wages through any agreed limits, statutory or not. Demand management cannot in fact deliver permanent full employment. It is impossible to forgive Heath’s poor understanding of the limits of his own economic knowledge; the death of Macleod and the absence of a counterweight at the Treasury subsequently was a disaster. Some part of the failure lies with ill luck: Macleod’s death itself; the Yom Kippur War; the temperament of Enoch Powell.

But as Ziegler unsparingly shows, the tragic dimension of Heath’s story, the story of the destruction of a man who was very nearly great, is that the central cause of the failure was himself. Where did the man who easily got his soldiers to love him go? What happened to the assistant Whip who was as popular as the young John Major? Or the Chief Whip who well knew how to handle the unpleasant far right, morphing as they did and do from League of Empire loyalists to the Suez Group, to supporters of Ian Smith and apartheid South Africa, to hangers and floggers and finally to those whose anti-Europeanism regards any who take a different view as traitors to their country? Where did his sense of self-protection, to put it no higher, go? People described the young Hea th as the life and soul of any party; how could he become the insensitive boor of whose nightmarish behaviour Ziegler gives so many examples, to which everyone who knew Heath could add many more? How can you try to lead a country and eschew all the normal political arts of personal leadership?

Ziegler writes the story like a good novelist, and as readably. No pop psychology, just the evidence. We have the story of poor Kay Raven, never receiving a reply to her devoted letters — but furiously resented when she finally gives up on him and marries someone else. Hers stands for a thousand soured friendships, personal and political, over the next 60 years. Ziegler shows us the relationship between these painful personal failures and the greater political failure. ‘Why don’t you talk to me?’ says the faithful Sara Morrison when he just sits and plays the piano. ‘But I am talking to you’ is the answer.

This is the Heath I knew: so much more complex than current Conservative mythology allows; maddening, touching, intermittently horrible, very nearly very great; self-created; self-destroyed. Hugely more interesting than Wilson or Blair; and, though he would have anathametised me, not for the first time, for saying so, the essential precursor of Margaret Thatcher.

Comments