Lots of people have subsequently discovered this important imperial maxim: ‘Don’t invade Afghanistan.’ But the first western power to demonstrate the point of it was the British, in the late 1830s. The First Afghan War is the most famous of Queen Victoria’s ‘little wars’ for its almost perfect catastrophe. The British went in, installed a puppet emperor, and three years later were massacred. The story goes that only one man, Dr Brydon, survived the march back from Kabul to Jalalabad. Actually, there were a few more survivors, though not many. The celebrated canvas of Dr Brydon’s solitary arrival, Lady Butler’s ‘The Remnant of an Army’, has stuck in the communal mind. It was the first really extensive British setback, and encouraged all sorts of independent thinking about the subject peoples from the 1857 Mutiny onwards.

The story has been told many times — and I myself wrote a novel about it ten years ago, The Mulberry Empire. I invented most of it and did little research beyond reading about 50 books on the subject. If there is an obligation on novelists to cover every point of view and to describe characters in accordance with their historical reality I have not yet heard of it.

Historians, on the other hand, do have an obligation to write truthfully and to try to find out what everybody said about the subject at the time. Amazingly, no western historian until William Dalrymple has used Afghan sources in a narrative history of the war — there is an interesting, though demanding book of a non-narrative sort by Christine Noelle called State and Tribe in Nineteenth-Century Afghanistan which does go into these sources. (Only very recently have historians started to look at Russian sources, even, and Russia was the great rival to the British in this corner of the Great Game.)

We are told that there is a lively school of 1970s Dari historians who use Afghan sources, though I am unable to tell you anything else about them, and I can’t see that Dalrymple has made any use of them either. I knew of the existence of some of these writings — for instance, the Akbarnama, an epic poem about the doings of Akbar, the leader of the successful uprising against the British. However, I decided, while writing my novel, that it was going to be a great deal of effort to track it down and have it translated, so I just made it up instead.

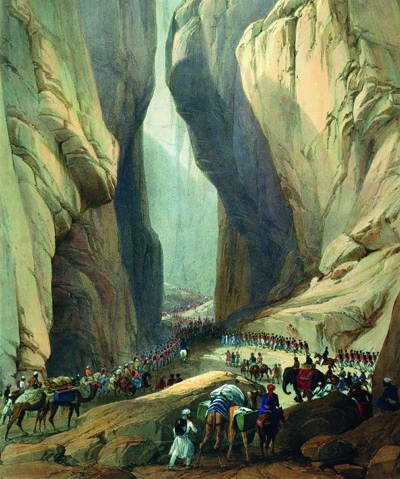

The story, as told from conventional sources, runs like this. The British, expanding their eastern empire from Calcutta, started to worry about Russian expansion in Central Asia. They wooed the Afghan amir, Dost Mohammad, until the viceroy, Lord Auckland, decided in favour of a vain, more anti-Russian figure called Shah Shujah-ul-mulk. A large army set out, overthrew Dost Mohammad, and imposed this pathetic puppet. Rebellion soon broke out. After three years, Dost Mohammad’s son masterminded a brilliant insurgency, first killing all the British leaders, then offering the remaining officers, soldiers, sepoys, women and children the opportunity to evacuate.

In the course of their retreat through the Afghan passes in midwinter, Akbar’s forces had no difficulty in killing almost all of them. Subsequently, the British despatched a punitive force which burnt most of Kabul and committed any number of atrocities before retreating. Dost Mohammad returned to power and ruled very successfully for decades, establishing the present-day borders of the country. The British never went near the place again for another 40 years.

Oriental sources, in Dalrymple’s telling — which are enchantingly written and often surprising — add a number of interesting points to this without essentially contradicting most of it. First, we discover some of the details of the vacillating Afghan tribal loyalties — a notoriously convoluted subject. In English retellings, the Afghans tend to form a single, unified, pro-Dost Mohammad front. Here, they become individual princes, with good cause to bear grudges.

These sources, however, have their limitations. They are rarely an accurate guide to events. At the point where Macnaghten, the British commander, was murdered with knives, the main Afghan source has Akbar indulging in a fine epic speech, hundreds of words long: ‘Your mind is darkened with black smoke and vain imaginings! Now you had better come with me into the city of Kabul!’ Colin Mackenzie, a British officer, reports only confusion and a savage outbreak of violence, which is much more likely to have been the case. The same goes for some of the Afghan comments on the behaviour of Alexander Burnes with his Afghan mistresses — simply put, it is intrinsically unlikely.

The main piece of literature which is used for the first time to create a revisionist reading of the episode is the ‘autobiography’ of Shah Shujah-ul-mulk, the puppet of the British and onetime owner of the Koh-i-nur diamond. It has never been translated into English, and without seeing it, it is difficult to know how important it is. Certainly, most of what Dalrymple uses is not autobiographical but a hagiographical continuation by a Mohammad Husain Herati.

Shujah has always been regarded as a disastrous leader — weak, petulant and deeply unpopular. Dalrymple describes him as ‘a remarkable man: highly educated, intelligent, resolute and above all, unbreakable’. But, in scrupulous honesty, he includes much evidence to the contrary: Shujah’s insistence in exile that the royal standards be maintained, for instance, or his unpleasant habit of mutilating his servants when they irritated him, with the result that the royal court appeared to be a collection of handless, one-eyed, limping invalids.

After Dost Mohammad was deposed, he refused to meet Shujah, and the British in turn refused to hand him over to Shujah to be executed. Dalrymple comes perilously close to the view of Shujah’s hagiographer in failing to ‘understand why Dost Mohammad Khan rudely chose not even to pay his respects at court’. I’m not convinced, either, by talk of Shujah’s mastery of tactics in demanding more troops to protect his position at the end. He had been constantly asking for more troops, more body servants, more dignity and more pomp from the British, and they were probably tired of these requests before they heard, for once, a justifiable one. After all, a stopped clock will be right twice a day. Was he, as Dalrymple claims, popular among the Afghans after the British eviction, before he was murdered by Akbar’s men? I don’t see how one could ever know, but it seems improbable.

Nevertheless, although the direction of the narrative is not changed as much as Dalrymple might wish by the extensive use of these fascinating and important sources, the detail is greatly enriched, and a lot of material which remained completely baffling to me has been explained.

The point of this story at the moment lies in its parallels with the present-day situation. Rabble-rousing Afghan leaders in the 1990s asked the young if they wanted to be considered sons of the heroic Dost Mohammad or of the quisling Shah Shujah. Struck by the parallels, I not only wrote my novel on the subject, but also articles for this magazine pointing out the historical -recurrences and the potential for -disaster.

Dalrymple goes into it extensively: it is amusing to discover that Karzai, the present leader, comes from exactly the same sub-tribe as Shah Shujah. He may be led by these parallels to overstress the role of religion in Dost Mohammad’s resistance. Other observers of the time describe the Afghans, far from being proto-Taleban in the 1830s, as being rather strikingly irreligious.

In Dalrymple’s usual happy style of historical narrative, applied to a fascinating, neat and highly suggestive series of events, this long and involved book will be a great success, and bring the famous story to a large new audience.

Comments