According to Arturo Toscanini, ‘any asino can conduct, but to make music is difficile’.

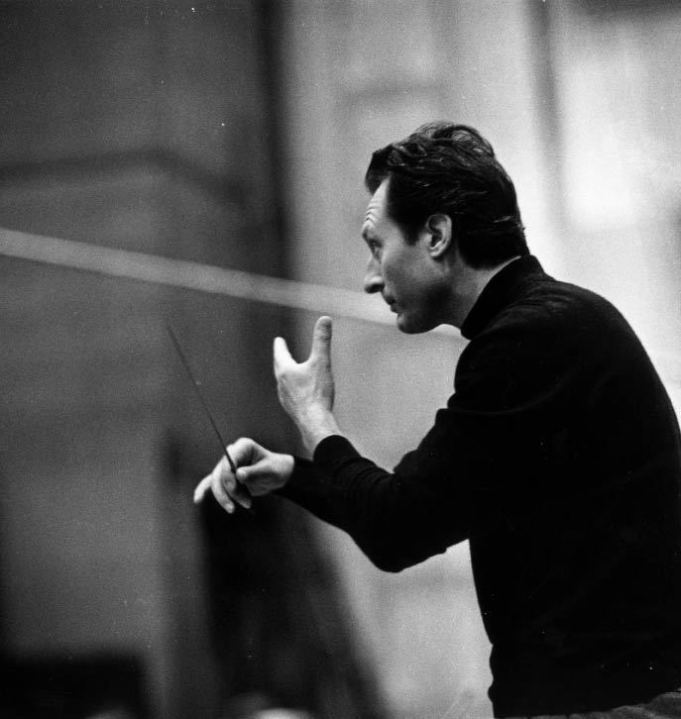

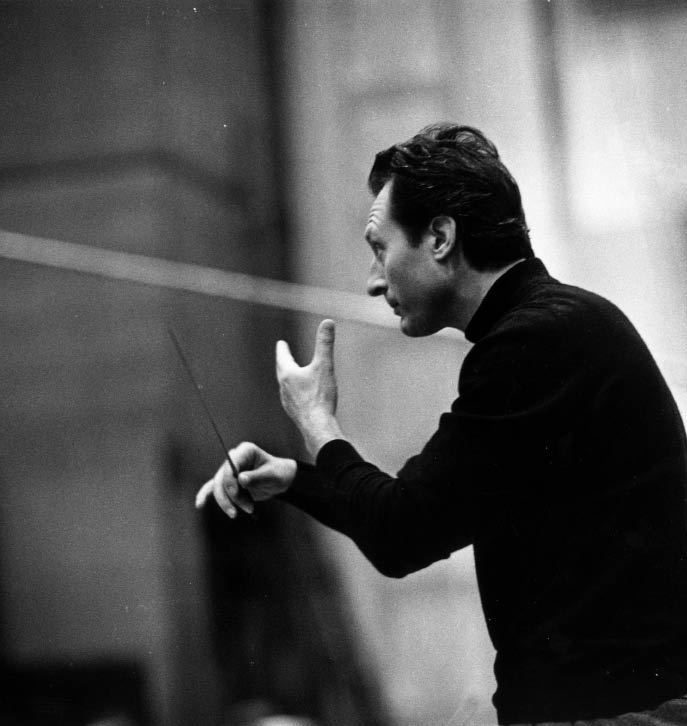

According to Arturo Toscanini, ‘any asino can conduct, but to make music is difficile’. The technical side of conducting did not appeal to Carlo Maria Giulini, the subject of Thomas Saler’s highly illuminating biography. He was an immensely spiritual man, ‘an old-fashioned poet in a world of ego- maniacs and prosaic technicians’ in the words of Martin Bernheimer. In many ways the two maestri were polar opposites, Giulini (who died in 2005) being a gentle aristocratic in demeanour, while Toscanini behaved like an irascible bulldog.

Giulini’s spirituality was certainly not wishy-washy and Saler indicates that the themes of his religion — ‘that we are uplifted by suffering; it is only through giving that we receive’ — permeated his performances. ‘He exuded an almost saintly aura which sooner or later was transmitted to his audiences’ , wrote Donald Henahan in the New York Times. Giulini was sent to the front in Croatia to fight the Yugoslav partisans in 1940:

A pacifist with a deep hatred for Mussolini and the fascists, Carlo had made a pact with his two brothers, Seno and Alberto, that they would not kill under any circumstances.

He asked:

How is it possible to live without faith . . . to think that inside the human body there is no soul? I can only tell you I have this gift of faith.

He had no idea how to write a cheque and had zero talent for admin. His wife Marcella did everything practical. He was not, however, wafting around on clouds all the time. Saler tells us that he indulged his passion for football, in particular Juventus. He was distraught when Marcella suffered a stroke in 1980, and even more so when she died 15 years later. But he reflected: ‘There is so much suffering in the world. Why shouldn’t I suffer too?’

After his wife’s stroke had prompted him to resign as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, he said:

What I know with absolute certainty is that in this moment Marcella — the woman who dedicated all her life to my and our children’s sake and to my work — needs my help, and I shall give it to her with all the strength of my love.

Ernest Fleischmann, the executive director of the LA Phil, said something similar: ‘She had taken complete care of him over 38 years of marriage and now he felt it was his turn to do the same for her.’

Does Giulini appear flawless? Robert Musil said of Herman Hesse that ‘he has the weaknesses appropriate to a greater man than he actually is’. I am not sure whether Saler differentiates between the image and the true self. I found it refreshing, when taking a beautiful girlfriend clad in Chanel backstage after Giulini had performed Beethoven’s Ninth, to notice that the eyes of this saintly individual followed her receding figure as she retreated. I glimpsed the man.

He slowed down later in life, and Saler quotes Harold Schonberg of the New York Times complaining that Giulini confused ‘slowness with profundity’. His style was certainly reverential and increasingly contemplative. Such was his aura, he was convincing even when wrong; and although he may have created his own myth— or simply stumbled upon it — he was humble enough not to believe it himself.

He was imbued with great integrity and nobility of spirit — nowhere more evident than in a DVD of him conducting Bruckner’s 8th Symphony or, combined with youthful passion, the ‘Dies Irae’ from Verdi’s Requiem,which has to be seen to be believed. Thomas Saler’s achievement in this book is considerable.

Comments