When a man is tired of Samuel Johnson, he’s tired of life.

James Boswell intended his biography of Dr Johnson, published in 1791, to be no mere chronology, but a life packed with the minutiae of ‘volatile details’. Thus he presented a deluge of correspondence, liberal literary extracts and copious Latin quotations; extensive conversations with ‘utterances from that great and illuminated mind’ (always prefaced by an emphatic ‘Sir!’), as well as the abject prayers poured from what Johnson called his ‘soul polluted by many sins’. Delivered with magnificent aplomb by David Timson, Johnson bursts from these 51 hours as an intellectual and physical colossus.

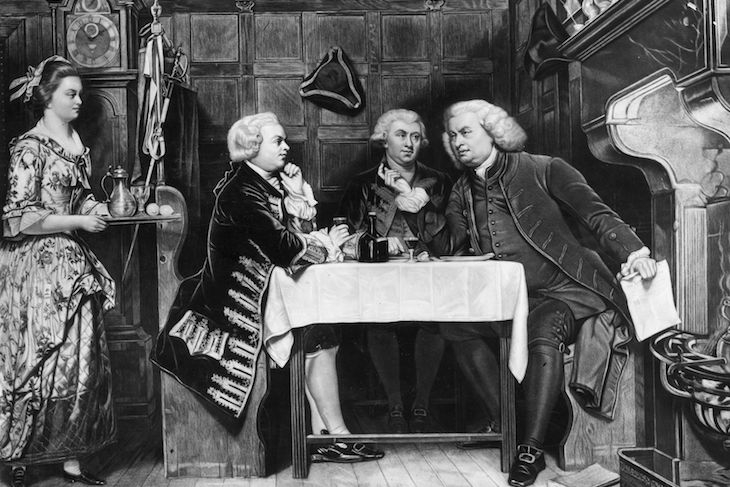

Timson’s vocal range for the variety of texts is masterly, and his accents are superb, from Johnson’s Birmingham, as rough ‘slow and deliberate’ as his shambling manner, to Boswell’s brisk and elegant Scots, and the prim, pedantic Irish of Oliver Goldsmith. Listening transported me into the Mitre Tavern, coffee house or club, as Johnson threw out conversational challenges (on the ‘mysterious disquisitions of ghosts’; or what is the proper use of riches?) to the assembled company while dining with ‘coffee and old port’. I was part of Johnson’s ‘frisking’ with Joshua Reynolds on the Thames, talking with Boswell for four whole nights, or debating ‘as long as the candles lasted’ with Henry Thrale.

The two of them met in 1763 when Boswell was 22 and Johnson 53, and their mutual devotion became absolute. ‘I hold you in my heart of hearts,’ wrote Johnson, whilst Boswell assured him that ‘a more perfect attachment has not existed in the history of mankind’. So intense was their love that Mrs Boswell scoffed that she had heard of a bear led by a man but never before of a man led by a bear. Despite his constant self-chiding for being a sluggish ‘idle fellow’, Johnson’s output was astonishing. His ground-breaking Dictionary alone was a staggering achievement; his Lives of the Poets swelled to 56 volumes; and his editions of Shakespeare were fully annotated. Then there were the poetry, the plays and a mass of powerfully intellectual essays for periodicals such as the Rambler and the Idler, frequently written as hastily as a letter.

But Boswell was not merely charting accomplishments. He wanted to create a multi-faceted Johnson for posterity, including the pleasure he took in draughts, his attempt to learn ‘knotting’, and his fondling of his much-loved cat, Hodge. Splenetic, forthright, irascible and offensive Johnson could certainly be in expressing his opinions. He referred to the successful poets Derrick and Smart as a flea and a louse, and thought balloon flight a mere fleeting jest.

But Boswell also recorded Johnson’s ‘humane and liberal heart’, detailing ‘a thousand instances of kindness’. He applied for Charterhouse shelter on behalf of aged and infirm friends, treated his servants, especially the Jamaican Francis Barber, generously; grief-stricken at the death of Thrale’s son, he would have gone to ‘the extremities of the world’ to save him. He was inordinately fond of his dear ‘Tatty’, the large, florid woman 20 years older than himself, with ‘bosoms beyond normal protuberance’, whom he married when he was 26 and whose wedding ring he kept in a little box after her death.

The famous aphorisms jump out — oats being the food for horses and Scotsmen; the woman preacher being like a dog walking on its hind legs — but Boswell gives us far more in Johnson’s humour, his sincere piety, and his fortitude in enduring lifelong suffering from ‘vile melancholy’ and infirmities caused by his childhood scrofula — as well as in his boundless intellect and interests. Trips to Scotland and around England and Wales engrossed him (he viewed shipbuilding at Portsmouth from a tempest-tossed yacht), but he was always drawn back to the ‘gaudy bait’ of his beloved London.

It is a man’s fault if his mind becomes ‘torpid’, Johnson proclaimed. Listening to Boswell and Timson’s tour de force is a guaranteed antidote to torpidity.

Comments