Two years before the outbreak of the first world war, a Royal Navy officer, addressing an Admiralty enquiry into the disturbing question of lower-deck commissions, ventured the cautionary opinion that it took three generations to make a gentleman. It is hard to know exactly what he meant by that endlessly morphing concept, but if it bore any resemblance to the historical compound of avarice, bad faith, dynastic ambition and family selfishness that dominates the pages of Adam Nicolson’s dazzling narrative, then the one consoling mercy is that it has always taken a good deal less than three to unmake one.

There are gleams of humanity, courage and honour to be found in almost every chapter here — the extraordinary Eliza Pinckney, the melancholy Harry Oxinden, even poor Joan Thynne, so old (40) and so fat, as her loving daughter-in-law told her, that all she was good for was to manure her grubby little dower house — but on the other hand, take the case of Sir William Plumpton. The Plumpton family had held the manor of that name since the 12th century, but it was under Sir William, son of the Sir Robert who had fought at Agincourt, that the family finally came to prominence, rising and falling with the Lancastrian cause in a miniature parody of the convulsive and ruthless age in which they lived.

There was nothing that Sir William would not have done to bolster the Plumpton fortunes — infant ‘heiresses’ flogged off to Yorkist lawyers, a legitimate son and wife squirreled away — but then the gentry world he inhabited was never the cosy haven that tradition and theory have described. For more than 500 years, the theory goes, they have stood between the nobility and the rest of the country, a sort of combined resting place and conduit between the two, a canal lock in the great waterway of national life, smoothly engineered for the safe transportation of the upwardly mobile and the efficient voiding of its failures.

It is a nice theory — and one England has always been fond of — but as The Gentry shows, it is not one that stands up to inspection. In the 17th century that genial hedger and divine, Thomas Fuller, described the yeoman’s world as ‘a temperate zone between greatness and want’, but for those who lived closer to the sun, unsure whether to stick or twist, and prey to the demands of the great magnates above and the predator ambitions of lawyers below, the potential perils of the gentry more than matched any possible rewards.

The gentry were not the only class at the mercy of national events, embroiled in civil wars whether they liked it or not, but the difference is that their stories can be read. The letter collection on which the Plumptons’ history is based is unusual for the medieval period, but from the Tudors onwards the lives of the Thynnes and Throck-mortons, the Oxindens and Oglanders are vividly preserved in account books and estate records, business transactions, spies’ reports, official and private letters — harassed letters from husbands adrift in London, harassed letters from wives bravely holding things together in the country — and above all in the records of the law courts where so many of them ended up.

You could buy half of England on the strength of the legal fees that mount up through the course of this book, and yet one of the great constants of the story is that nobody ever seemed to learn the lesson. By the time the Tudor lawyers had finished with the Plumptons there would be nothing but bones, but that never stopped the Thynnes and the Touchets — always good to come across one of the maddest families in English history — in the next century, or Hugheses in the early 19th, going to law with the same ruinous gusto.

There were always enough winners coming out of these proceedings to make it worth someone’s while, of course, and it is possible that the losers should just be seen as the inevitable casualties of the genetic imperatives that drove these gentry families. In the course of the book Nicolson deploys different metaphors to convey the point, but however it is dressed up the overarching theme of this history — the one fact that draws all the fights over dowries, jointures, status and land into an intelligible pattern — is the brute belief that the family ‘corporation’ is more important than the individual.

It has its points — the fanatically Protestant Throckmortons could happily sit down with the family’s equally fanatical Catholics — but it is a hard and unrelenting dynamic that Nicolson explores in a history that deepens with each successive chapter. There is an exhilarating narrative sweep that takes the story across the centuries, but above all there is a unity of theme and place that roots it in English history and the English landscape.

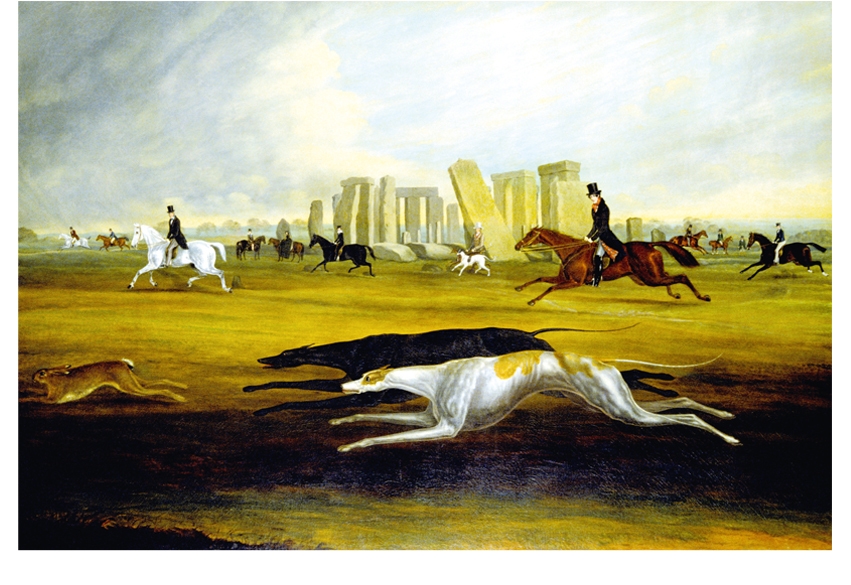

And The Gentry is as much about landscape as it is about the history of a class. If land — money in the 18th century — has always dominated gentry lives, they in turn have left their richly seductive imprint on it; and it is this interaction of the human and the physical that brings out the best in Nicolson. Towton, Palm Sunday 1461, its streams clogged with 28,000 Lancastrian and Yorkist dead, out-Somme-ing the Somme as the bloodiest day in English history; the view over the channel from the Isle of Wight, where Sir John Oglander, gloriously in love with himself and all he stood for, took his evening ride; a path across the downs, the grass worn away to chalk — Nicolson responds to all the varied landscapes with a ‘feel’ and familiarity that never cloys or descends into sentimentality.

And that is what makes this the book it is. ‘There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,’ wrote Walter Benjamin, and this history never loses sight of that. Oglander allowed his most casual family dependants 60 times his servants’ wages; the genial Oliver Le Neve — the perfect type of the Tory squire before Addison’s Spectator made the breed ridiculous — was one of London’s rack-rent landlords; Acland’s patrician munificence coexisted alongside estate children so hungry they would steal the scraps put out for birds.

And even Eliza Pinckney — keeper of the Virgilian flame, Mother of Patriots and the real hero of this book — floated a New World life of courage, honour and achievement on the back of the slave trade and a workforce called, with appropriate valuations, names like: ‘York £1, Cork £60, Glasgow £90, Lazy £20, Muddy £80, Bounce £70 and Monday £40.’ It is a bitter thought, and in a history so generously alive to the cultural and physical richness of the gentry inheritance, a brave one. This is an enviably good book.

Comments