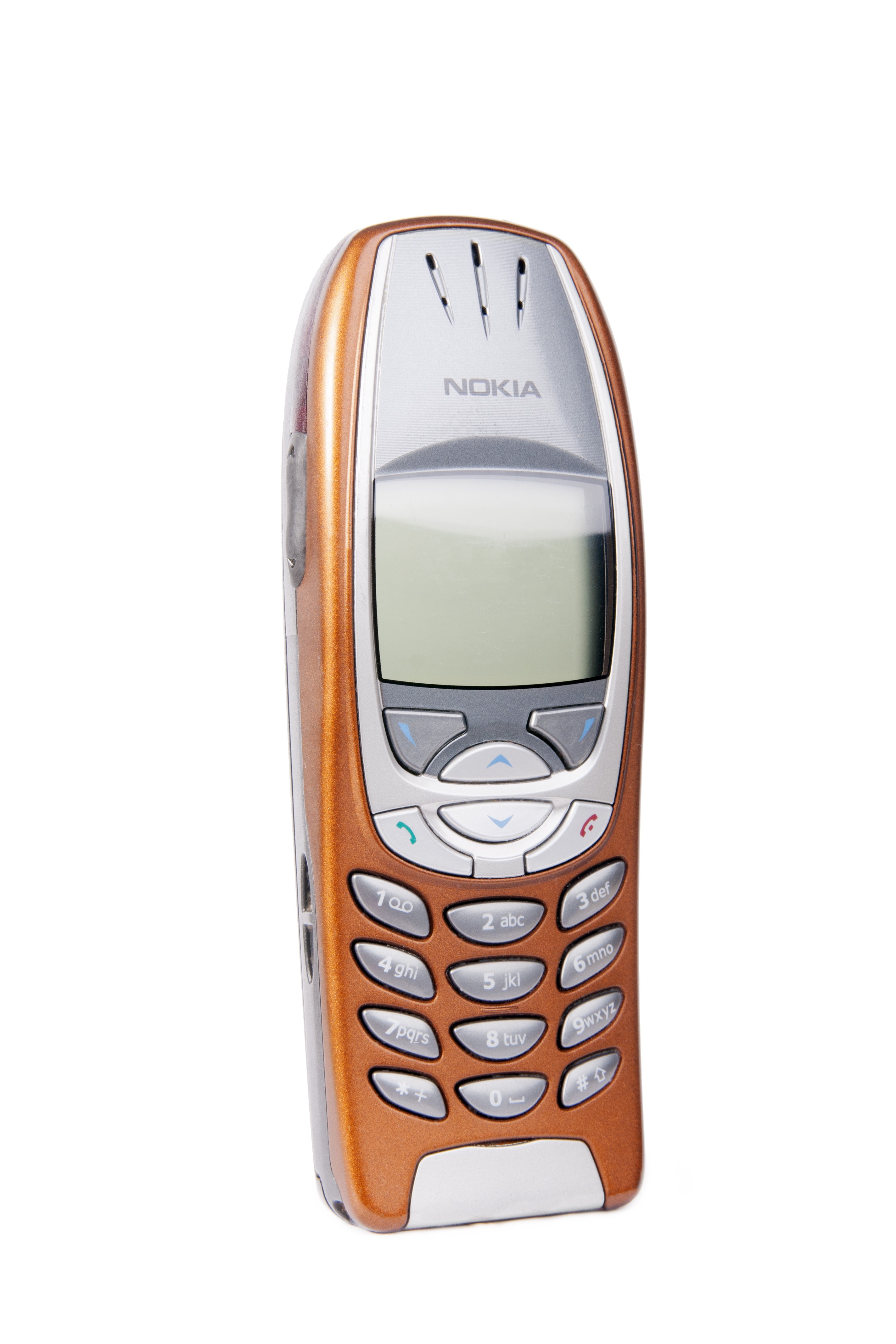

Without much fanfare, the Nokia phone has died. I got my first mobile phone, a Nokia, at an age that is by most lights too young. I was in what Americans call the fourth grade, which means I was ten or 11. The phone in question was a cutting-edge Nokia 6820, which a contemporary Nokia press release claims was ‘specifically designed for enterprise use, with a full keyboard to offer faster text-input and easy navigation for advanced messaging like mobile e-mail’. I certainly had never sent an email at that stage in my life, and I operated no enterprises.

At first I thought very little of that phone, by which I mean I thought very little about it. Our relationship was not a passionate one. I liked that it was silver and light blue. I really liked that it had that general Nokia brick shape, with its clever flip-out keyboard that, held in two hands, allowed me to type on a Qwerty-style keyboard, not like those chumps hitting three twice to make an ‘e’ on the mobile phone flavour of the week. I can’t recall that Nokia ever running out of battery, but I distinctly recall, one time when I must have been about 14, that it connected perfectly to a call I took in the middle of absolute nowhere in the Utah desert, about as remote a place as my relatively empty and open country contains. But mostly, what I remember about it is nothing. I didn’t think about it very much at all.

As cooler phones started to come out, such as the Motorola Razr, it stayed my phone. ‘Personal digital assistants’ with colourful screens came and went and their capabilities were integrated into phones, and still it stayed my phone. I played catch with it, or just threw it in the air and let it clonk on to the ground. It was fine, since it was made of some kind of magical plastic, stronger even than Lego. Later, when my classmates and I were in high school, and people were on Blackberry Messenger, it still stayed my phone, and I still played catch with it. And its hardiness was not just a matter of its exoskeleton; it took a dunk in a pool or two, and it would die for a day, but then blink cheerily back to life once it had dried out. I played Snake here and there if I was bored without a book or magazine in a waiting room, but in general my phone was a trusty but minor part of my life.

Time went by, the iPhone came out, and I texted more people about more things, still flipping the hard plastic keyboard of that Nokia to do so. I got my first girlfriend and memorised her number because I knew I wouldn’t reliably have my mobile on me. And then one day, checking my phone on the walk home in Manhattan, I noticed my Nokia had no service, not even one useless bar. I had had this thing for over a decade, and it had heroically received calls and texts all over, certainly anywhere in New York. What gives? My tech-savvy mother broke the news: the carrier had turned off the 2G network that it ran on, presumably because no one really used it any more. The hardy phone survived, but the world was moving on.

I played catch with it, or just threw it in the air and let it clonk on to the ground. It was fine. It even took a dunk in a pool or two

If memory and iPhoto serves, it was 2016 when I finally relented and got an iPhone. Boy did this change my life. First off, people stopped complaining that my texts were green. Second, I could get rid of other devices: the Garmin satnav on my dashboard, the iPod classic with a carefully curated music collection mostly downloaded at 99 cents a pop. I could send and check emails quickly and efficiently from anywhere, something necessary for a new state I found myself in, despite my undergraduate philosophy degree, known as ‘employment’. Little did I know this meant I would, forevermore, be at work always and never. The line between ‘at work’ and ‘not at work’ had been permanently blurred – as it had been for everybody.

I marvelled at the sophistication of the games you could entertain yourself with for hours on a plane, like Angry Birds, which I’d tell people about like it was big news and get some combination of chuckles and eye-rolls. Oh, and I signed up for something called Twitter out of a sense of professional obligation. At first I used it only on my laptop, but over the years all of these tremendous affordances became things I could not live without, or felt I could not. They became reflexes, compulsions. They became something I could feel in my neck. I became so good at typing quickly on my iPhone that I actually feel I write full-length essays better there than on a proper computer. I was hooked like a herring.

From young kids who need distracting at a restaurant so their parents can eat, to teens exploring the social world as they form their personalities, to adults who use the excuse of work to explain why they spend quite so much time with phone clutched in hand, I don’t know anybody today who thinks our relationships with our smartphones is healthy. The guiding metaphor is addiction, with clumsy semi-scientific explanations about ‘dopamine hits’ and ‘brainrot’ now a dime a dozen. I am not immune, and perhaps because I came to smartphone ownership late I am extra vulnerable. I wish every day that I could throw my phone in the fire. I joke that I should read more – that it is absurd that a professional magazine editor has not read The Brothers Karamazov, that scrolling the news makes me despondent about the world and no more informed about it, that when I spend time in person conversing with a friend we will embarrassingly rehash what we have texted one another almost as though to reassure ourselves that the flesh and blood person in front of us is the same being as the scroll of text we engage with so constantly. We know these things are bad for us. Something must be done, we think.

According to a tracking app I didn’t download or want to surveil me, but comes standard with an iPhone anyway, my screentime this week is a daily average of four hours and 36 minutes, down 22 per cent from last week. How was that time spent? It wasn’t a total waste, of course. I used my iPhone navigating to the grocery store. I did the New York Times crossword on it, which I do cuddling with my wife at night. I texted friends around the world. I FaceTimed my dad, who has cancer and can’t travel. If I had an old Nokia brick with a snazzy flip-out Qwerty keyboard, he may not have been able to feel nearly so close to his infant granddaughter these past few months since she was born.

But, still. Why do I miss my Nokia days so badly? Why can’t I shake the feeling that, while technology has in general been a great thing for human progress, it would have been a whole lot better for me if mobile phone technology had gone as far as about 2004, and no further?

Why can’t you?

Comments