‘Nothing escape’s the wolf’s fangs,’ thinks the narrator of Katerina. Through an outlandish sequence of chances and choices, somehow its author did just that. Aharon Appelfeld, a child of assimilated parents, lived in the old Jewish heartland of Bukovina. In 1940, short-lived Soviet occupation gave way to Nazi control. His mother was murdered and his father disappeared. Young Aharon escaped the Czernowitz ghetto and survived as a wild child in the forests, sheltered by a village prostitute, then as the ‘slave’ of a Ukrainian bandit gang.

When the Red Army arrived he cooked for them before, via a peril-strewn route through Italy, he migrated to Mandate Palestine. In newborn Israel he laboured on the land, treated not as a heroic Holocaust survivor but a contemptible reminder of diaspora weakness. As Appelfeld (who died in 2018) once told me in an interview: ‘I was alone, in the fields of the Judaean Hills. I thought, is this my landscape? Is this my language? This was a moment of despair.’ Yet out of that desolation he began to write, in his flinty, rugged, hard-won Hebrew, a series of novels that restored his annihilated childhood world to radiant life. After long years of separation – each thought the other dead – he also found his father.

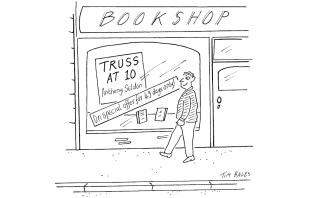

Penguin Modern Classics have issued Jeffrey M. Green’s translation of Katerina (never published in the UK before), along with Appelfeld’s luminous memoir The Story of a Life and Badenheim 1939, his more playful but sinister fable of a community on the verge of extinction. Katerina, however, is pure Appelfeld – set among humble people, swept by waves of primal emotion, expressed in a simple, exalted, often Biblical language, treading a visionary line between memory and myth. Green captures both its prophetic and demotic sides.

Katerina begins and ends as the eponymous elderly narrator returns to the abundant woods and meadows of her birthplace. In this ‘green eternity’, she finds that ‘everything is in its place, except for the people’. Katerina remembers a harsh, violent Ukrainian home of the 1880s: ‘Anyone born in a village knows that life is no party.’ She revels in the lush Carpathian countryside around her, but otherwise faces an endless vista of drudgery. Then she goes to work for a Jewish family. Even though ‘there’s nothing easier than to hate the Jews’, she grows to admire and love them and their ways. At the tavern, friends warn her that Jews ‘change you from the inside’. Katerina, although a witness to anti-Semitic pogroms, murders and extortions, is duly, irrevocably, changed.

She learns fine Yiddish and knows how to keep the festivals and kashrut laws better than her hosts themselves. Appelfeld never sentimentalises Katerina’s virtual conversion: perplexed, her Jewish companions tell her to expect ‘the same stupidity and the same wickedness’ with them as everywhere else. And she routinely backslides from the ‘life of truth’ she seeks into drunken benders and reckless liaisons. When pogroms destroy the beloved, pious family she has been serving, she discovers other facets of Jewish life: first with the gifted, secularised pianist Henni (who tells Katerina ‘You’re my rabbi, you’re my Bible’) and later Sammy, a charming, feckless loser with whom she has a son, Benjamin.

An outcast herself, with ‘nothing to grasp except the hems of Jewish homes’, she loses everything when an inebriated thug smashes her baby against a wall. In a truly Biblical act of vengeance, she carves the killer into chunks. At the close of her long, lonely prison term this ‘murderess’ (‘a horror and a curse since time immemorial’) learns that the trains that twist like black snakes through the valley are taking Jews in their thousands to their deaths. At the war’s end, as jails and regimes collapse, she revisits the green land purged of the people she loved and vows to preserve the memory of that ‘hidden tribe’.

Katerina is studded with passages of raw brutality, sorrow and grief, and unsparing in its grasp of the psychology of lethal prejudice (one fellow convict confesses that ‘the Jews make my heart restless… and drive me out of my mind’). Yet the novel glows and soars with its heroine’s rapt commitment to the long-suffering people she has chosen, whose presence alone links her to ‘blue and silent worlds’. For readers eager to visit the unique fictional domain Appelfeld mapped, or rather rediscovered, this is the perfect place to start.

Comments