AN Wilson’s charming, 1840s terraced house sits on the brow of a hill, overlooking Camden Market in north London. Walking through the market recently, he was much taken with a particular stall.

‘There was a T-shirt for sale in the market, saying, ‘Too stupid to understand science? Why not try religion?” he says, laughing, ‘I like that. The people who think they’ve demolished religion by these scientific discussions think they’re in the same category. The questions posed by religion are very different from the questions posed by science.’

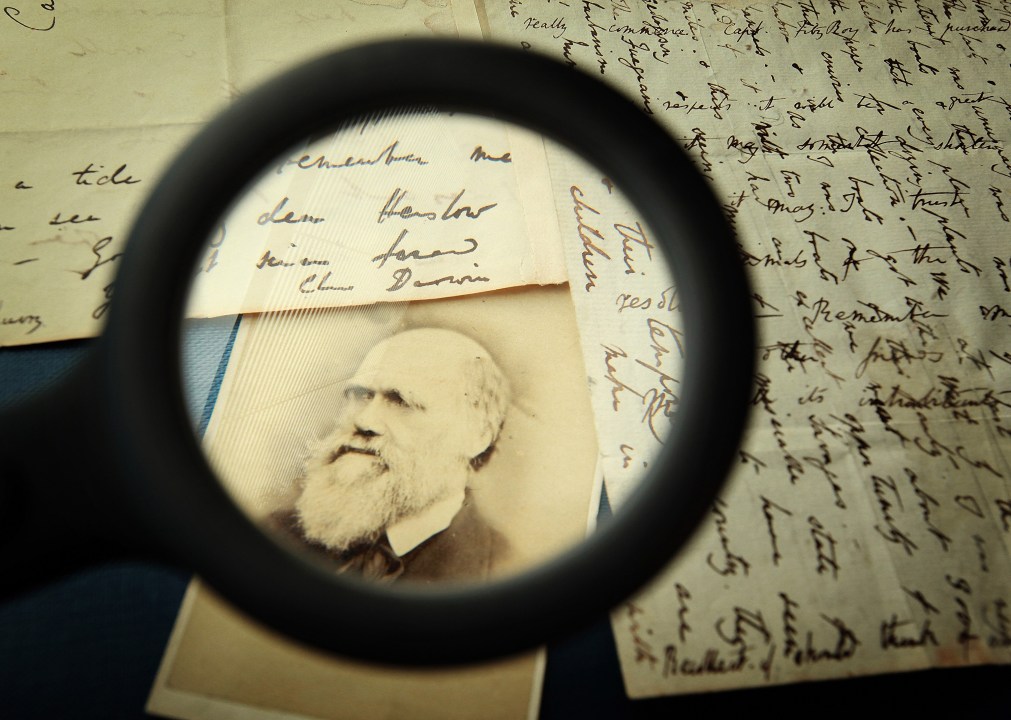

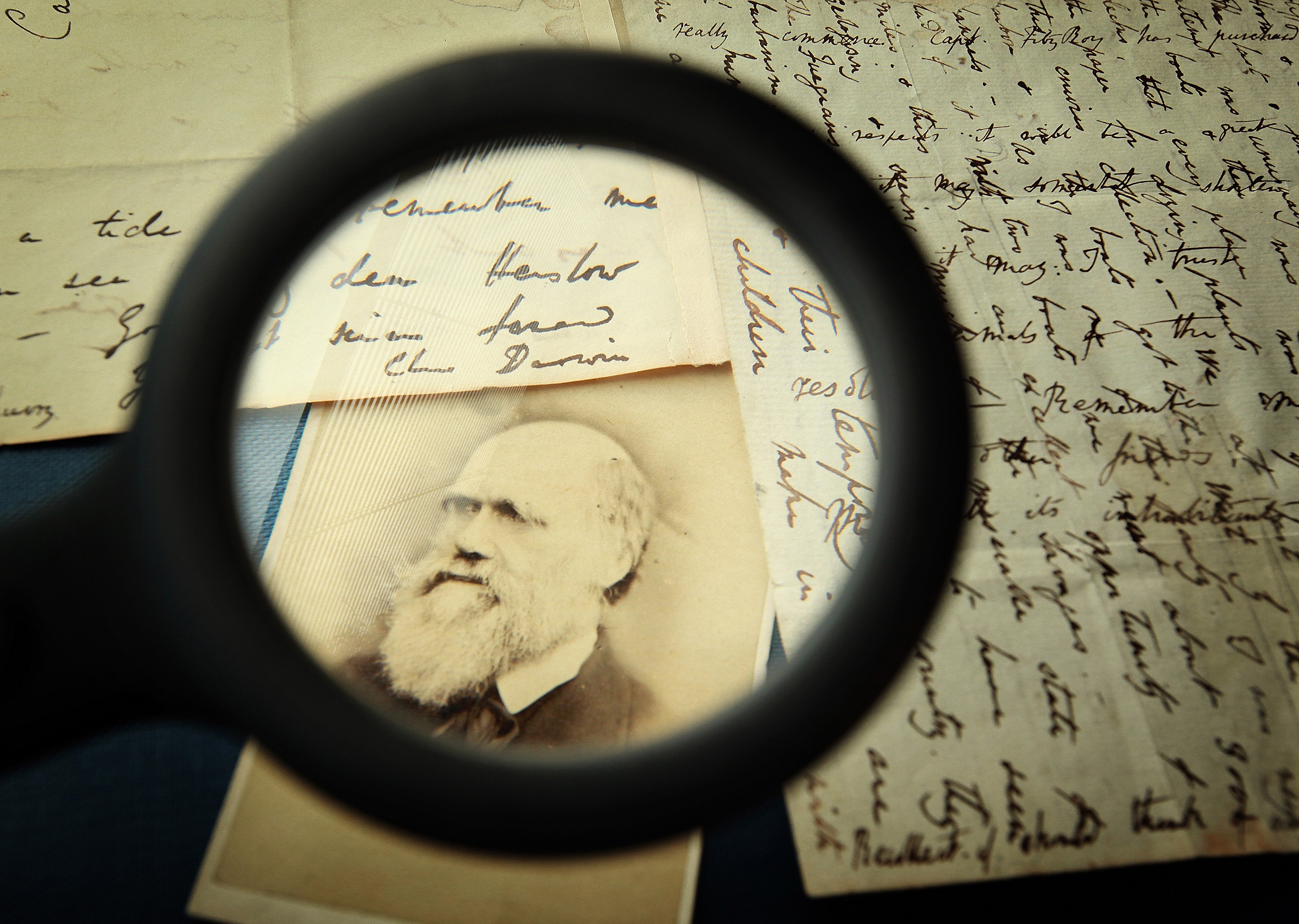

Wilson has just walked into a classic religion/science row with his new biography of Charles Darwin. The book certainly doesn’t pull its punches. The first line declares, ‘Darwin was wrong.’ Wilson goes on to rip into Darwin’s theory of evolution, eviscerating two of the theory’s foundations: the survival of the fittest and the idea that species evolved in slow, gradual changes, rather than the leaps Wilson believes in.

The book has divided critics. It was praised in the Spectator, but blasted by Neo-Darwinians, who back Darwin to the hilt. In the New Scientist, John van Wyhe, Director of Darwin Online, called the biography ‘one of the most unreliable, inaccurate and tendentious anti-Darwin books of recent times’.

‘He was really foaming at the mouth,’ says Wilson, laughing again, ‘He said I hadn’t understood the principle [of Darwinism]. Well, a child of two could understand the principle because it’s such a simple one. And that’s why it’s so attractive. They want to believe – and I can see the attraction of it; I believed it until I started on this book. I don’t get it why the scientific establishment minds so much, when they’ve discarded every bit of the theory. But they still use Darwin as their figurehead. The scientists want us lay people to just shut up, and be a bit more humble. Why should this Johnny-come-lately, a literary type, dare to write a scientific book?’

Wilson believes in the essential idea of evolution: that the horse, say, evolved from ‘a funny little animal about the size of a fox’ to what we recognise as a horse today.

‘We know that’s true,’ he says, ‘Everyone must accept, unless they’re crazy, that that’s happening.’

While Wilson accepts that fox-like horses developed into modern horses, he can’t accept that the building blocks of a species – cells, feathers, hairs – were themselves produced by evolution.

‘There’s no evidence in nature of a transitional thing turning into a cell,’ he says, ‘Darwin hasn’t demonstrated in his theory, nor has a Darwinian since, that such forms have come into being through gradual process.’

Wilson can’t accept, either, Darwin’s claims about how one species mutated into another. ‘There’s a famous blunder in the Origin of Species, which I thought was a donnish joke, in which he posits that a bear fell into the sea and turned into a whale. Or was it the other way round – that a whale got out of the bath and turned into a bear? Anyway, it’s ridiculous.’

Nor does Wilson buy that we’re directly descended from apes. ‘The explanations for how language evolved in the Descent of Man [1871] are ludicrous,’ he says, ‘We, the human race, seem to have a linguistic ability and a consciousness which is totally different. Obviously the apes are our cousins in some sense. But, when we say they’ve got a language, or dolphins do, of course they have some kind of means of communication. But think of the linguistic capacity of a baby. The idea that this can all be explained by slow, plodding, evolutionary materialism strikes me as so improbable.’

Wherever there’s a gap in Darwinian thought, the temptation is to explain it through religion – thus the T-shirt in Camden Market. But, although Wilson liked the T-shirt, he hasn’t bought it, literally or metaphorically. ‘I don’t think [the mystery of the origin of species] shows that there was a God who put it there,’ he says, ‘I don’t think theology has anything to do with it.’

That doesn’t mean AN Wilson doesn’t believe in God. Now 66, he has had a tempestuous relationship with the Almighty. In his 20s, he trained as an Anglican priest at St Stephen’s House, Oxford, before dropping out after a year. After nearly 20 years as an atheist, he now attends Church of England services at the nearby church of St Mark’s, Regent’s Park.

‘I had a phase of being a non-believer,’ he says, ‘I also realised, looking back, that I had a long, long phase – probably most of my grown-up life – of being a keen churchgoer without really believing it. Over the last ten years – I wouldn’t quite know when – I think I started believing, I don’t think it was ‘again’. I’ve never had any mystical experience at all, but I completely believe it now.’

Once you get onto the vexed relationship between religion and science, it’s hard to avoid the figure of Richard Dawkins. ‘Palaeontology shows there are weird little bumps and leaps [in evolution],’ says Wilson, ‘That doesn’t show God suddenly does the leap. It isn’t a matter, as Dawkins and co want to make it, of religious nutters versus scientists.’

‘Because Dawkins is a kind of lapsed evangelical Christian, he’s obviously terrified that something’s going to turn up one day, which will suggest to them that a hand – as in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement – is going to come pointing through the cloud at the plants or the apes.’

Wilson has been writing the Darwin biography for five years. He didn’t set out to do a hatchet job. ‘I had no intention to demolish him whatsoever,’ he says, ‘I thought of him as a dear old boy with a long, white beard, very fond of his family. I’ve always had a feeling of affection for him. I still do, really.’

‘It never crossed my mind that the basic tenets of Darwinism were wrong, until I sat down and read what scientists have written about him in the last 20 years.’

Wilson gradually builds up a devastating picture of Darwin, not least his pungent personal habits, which Wilson relates to lactose intolerance.

‘The privy was in the corner of the room,’ he says, ‘It must have been absolutely ghastly. Mainly burping and belching and making retching noises. Sometimes he was sick and he seemed to have had diarrhoea a great deal – which does explain why he doesn’t want to leave the house very much. At the same time, he did make an awful fuss about it. He was perfectly fit. There’s a certain person who enjoys being ill.’

Wilson also argues that Darwin’s belief in the survival of the fittest led to racist, eugenicist views. ‘When you read Hitler’s table talk, you can’t tell the difference between what Hitler was saying and what Darwin was saying in the latter stages of his life,’ he says.

To Darwin, Wilson argues, the fittest humans were the white, middle-class rich, like his own class. ‘He makes that absolutely clear in the Descent of Man – he more or less paraphrases Land of Hope and Glory before it was written,’ says Wilson, ‘He makes it clear they’re facing a catastrophe in Victorian Britain because of the feckless. Darwin leaves it rather vague what we, the educated folk, must do. His cousin Francis Galton picked up the ball and ran with it. The result was eugenics.’

Arguing against survival of the fittest, Wilson points to those species, including humans, who cooperate with and support their weaker members. Wilson also slams the related Dawkins theory of the selfish gene. He depends heavily on scientific advances in DNA to argue against Darwinism – and Dawkins. ‘The human genome, since Dawkins wrote that stuff in the 70s, has been studied exhaustively,’ he says, ‘Genes can’t be selfish. They’re impersonal things. It’s an extrapolation. It’s a result of putting this Darwinian, Victorian metaphor into the quite different science of genetics.’

Funnily enough, AN Wilson and Dawkins both taught at New College, Oxford, in the early 1970s. ‘I like Richard Dawkins personally, and I’ve always thought he’s a very nice man,’ says Wilson, ‘But I do wonder whether he ever regretted getting on to that [atheism] bandwagon.’

Oh, to sit between Wilson and Dawkins at High Table at New College – with crash helmet close at hand.

AN Wilson’s ‘Charles Darwin – Victorian Mythmaker’ is published by John Murray (£25)

Comments