‘Yee-ha!’ is the triumphant shout from a riding school in south London, where Hamza, a teenage boy, has just completed a gymkhana exercise in a faultless rising trot. He takes a hand off the reins and makes lassoing motions in the air to emphasise his point.

Hamza is wearing his school shirt and jumper (tie neatly rolled in a cubby hole in the tack room) above tracksuit trousers and borrowed riding boots. The sand-covered riding school has been built between the tower blocks of the Barrington Road estate and the railway line between Brixton and Loughborough Junction.

Lambeth is one of the poorest boroughs in London: 32 per cent of pupils qualify for free school meals, against a national average of 16.3 per cent. The borough has 103 schools and not a lot of space to spare. Which is why, on a Thursday morning, Darnell, Hamza, Gary, Lucy and Katerina, all from Landsdowne School, a special-needs secondary between Brixton and Stockwell, have decamped to the Ebony Horse Club under the railway arches. The club teaches children from local state schools to muck out and tack up, mount and dismount, tighten a girth and — as Hamza neatly demonstrated — master a rising trot.

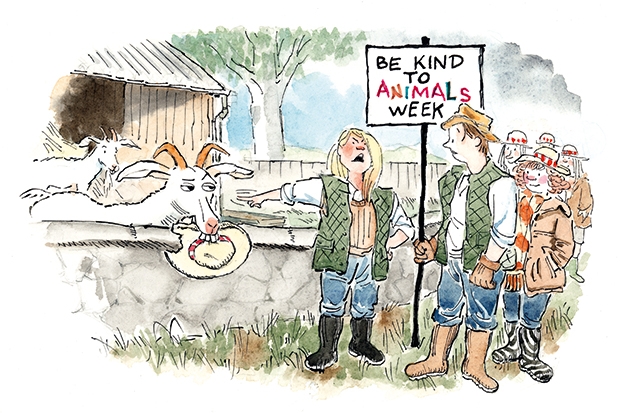

A growing number of inner-city schools are finding ways to bring a bit of rus into the urban environment. If a village school has a garden, a chicken coop and half a dozen stables, why shouldn’t an inner-city academy? There may be room for goats behind the bike sheds, chickens in a corner of the playground and beehives beyond the basketball hoops. Gateacre School in Liverpool has a wildflower meadow in the Year Seven yard.

At Charlton Manor Primary School in Greenwich, pupils have helped keep bees for six years. When a nest was found near the gates one summer, teachers panicked, while the children were curious. Headmaster Tim Baker explains he wanted to teach the children not to be fearful. Today, the school has three hives, a wardrobe of child-size bee suits and two after-school bee clubs, each with a waiting list. There have been ‘a couple of stings’, says Mr Baker, but the children have learnt about ‘getting stung and getting up again and getting on with it’.

Four years ago the school added 12 chickens — one named Nuggets— and the pupils eat their own eggs and honey at the morning breakfast club. At Charlton Manor, 67 per cent of the children come from black and minority ethnic families, 47 different languages are spoken and 82 per cent of the children come from families in the bottom 10 per cent of income in the country.

Mr Baker says the bees and chickens have been invaluable when it comes to teaching children about kindness, caring and respect for the lives of others. In a borough carved up between four gangs, with ten knife crime incidents a month, Mr Baker hopes that the chickens will teach children about the ‘finality’ of death: ‘By steering children away from death, by protecting them, we make it harder for them to understand it.’

At Quintin Kynaston School in north London they have not just chickens, but guinea pigs and three goats, which can be seen from the top deck of Finchley Road buses. The animals were introduced by a youth worker who had worked with disaffected teens on ‘outward bound’ courses. Headmaster Alex Atherton says the small farm ‘adds an air of calm to a particular area of the school where the kids can be quiet without a football flying at them. It has meant a great deal to the kids. It’s a countryside element in an urban environment.’ More than 80 per cent of the school’s pupils qualify for free school meals, 95 per cent are from BME families and more than 80 per cent speak English as a foreign language. You may recognise the name Quintin Kynaston. The school was in the news for all the wrong reasons when it was revealed as the alma mater of Mohammed ‘Jihadi John’ Emwazi.

‘Lots of the kids live in estates where they have someone living in the flats above, below and either side of them,’ says Mr Atherton. The chance to nurture a small-holding, be it ever so small, is a valuable one.

For schools where teachers don’t know the first thing about keeping chickens, it is Claire Peach to the rescue. Claire runs Hens for Hire and is evangelical: ‘All schools need chickens.’ At the beginning of term, she drives from her home in Burton-on-Trent, where she has kept chickens in the back garden for six years, to schools in Liverpool, Bristol, Manchester, London and Birmingham, with chickens and an Eglu — a lightweight plastic chicken house. Schools can hire two to eight hens for a term or a school year, and Claire collects and looks after the birds in the holidays. A similar scheme for beehives is run by Hire a Hive, though with rather more health and safety forms to fill in.

Claire says that too many city children ‘have no conception of the connection between chicken and egg’. When they see it in practice, ‘it blows their minds’. ‘A lot of children don’t have pets at home and it’s very important to teach children about care and responsibility for another creature.’

There is, of course, the odd tragedy. In October 2013, CCTV at Alma Park Primary School in Manchester caught three thugs breaking in and killing the school’s two chickens. The school’s secretary told me the children were ‘very upset’ and that Alma Park has not replaced the hens. It seems a shame.

Standing in the stable yard in Brixton, it is clear that trotting circuits of the riding school on Rocky and Shaney is a joy for the Landsdowne pupils. Hamza giggles so much he almost loses his seat, while Darnell, who has worn a look of surly teenage discontent for much of the lesson, breaks into a wide smile when he manages a perfect dismount, both riding boots hitting the sand at exactly the same moment.

Comments