In December 1996 Martin Amis told listeners of the BBC’s Desert Island Discs what would relieve his solitude were he to end up cast away in paradise with one piece of music, a luxury and a book for company. He chose Coleman Hawkins’s version of the jazz standard ‘Yesterdays’ as his only record — seduction music, he suggested — and opted for the luxury of an unlimited Sky Sports subscription package.

Amis’s preferred book, in this company, sounded similarly butch: John Milton’s Paradise Lost as edited by Alastair Fowler for the Longman Annotated English Poets series in 1968. Fowler’s edition of Milton’s epic poem remains a monumental feat of textual scholarship; a page frequently presents just half a dozen lines of blank verse above many hundreds of editorial words intricately tracing the poem’s echoes, the labyrinthine complexity of its allusions. Milton and Fowler are, Amis’s choice implies, Premier League.

So, too, is William Poole’s smart and original book on Paradise Lost, built upon the very best traditions of patient philological work represented by Fowler’s edition. It offers a complex literary history by way of an extended biographical reading of a single poem; it demonstrates with astonishing exactitude how Milton’s life and — most impressively of all — his reading enabled this epic.

It makes perfect sense to use this single poem as a focal point for the analysis of this particular life. Milton was from an early age absolutely convinced he would write his nation’s great heroic poem. During his tour of Italy, he impressed the literary academies by announcing himself as the writer of a Protestant epic (when he hadn’t yet written a word of it). And even though he didn’t much like his student days at Christ’s College Cambridge — he ‘never greatly admired’ the place, one early pamphlet remarks — he passed his time there with an unswerving clarity of purpose that would bring joy to the heart of many a modern careers adviser.

The life of an academic, churchman or lawyer were never for him; he spent his time writing in a variety of ‘lower’ verse genres, mastering the classical arts of eloquence, and reading very hard indeed for the poem to come. If Amis’s Milton is butch, it is so in part because the hyper-competitive, homosocial environment of 17th-century Cambridge made him so; early modern attitudes towards academic work and sleep — at least 16 hours of the former, three of the latter —could be crushing.

As Poole shows, when Milton set up as a private schoolmaster in 1639 he continued to drill the virtues of punishingly hard work into his pupils — whether he beat such lessons into them, as Milton’s first wife Mary Powell once claimed (according to the antiquarian John Aubrey), is swerved here. But the reading and work they did together was always done, by Milton at least, with one eye on Paradise.

This means that we need to expand dramatically the number of classical authors and influences at work behind the poem. We’ve long known that Homer, Lucan, Lucretius, Ovid and Virgil exercise transformative influences on the meanings of Paradise Lost; thanks to Poole we can now supplement this list with a much longer series of more obscure authorities — including Apollonius of Rhodes, Aratus, Dionysius Periegetes, Hesiod, Nicander, Quintus Smyrnaeus, and Oppian — who Milton engaged with very carefully both in his educational programme and his later poem.

Why should he put his pupils and us through this? Never one to undersell his aims (or, indeed, the virtue of reading voraciously), Milton gave his clearest answer in his pamphlet Of Education (1644), years before he began writing in earnest about Adam and Eve: ‘The end… of learning is to repair the ruins of our first parents by regaining to know God aright.’

Repairing these ruins likely hastened the ruin of Milton’s eyesight. His eyes were going in the 1640s and he was fully blind by 1652. He thus composed most of Paradise Lost — begun systematically in 1658 — by dictating it in batches of 10-30 lines to a variety of amanuenses, some of whose services he had used before his blindness struck. The first draft of one book of the poem would take around 50 bouts of dictation, the whole thing more than 500.

Milton’s hostile contemporaries were cruel about the disabling nature of the poet’s condition. One contemporary — knowing Milton had refuted Claudius Salmasius’s defence of the Stuart dynasty in his regicide pamphlets — asked whether he thought his blindness a divine judgment. Milton’s reply was a piece of characteristically forthright rationalism: ‘I am blind; Salmasius is dead: which is the greater judgment?’

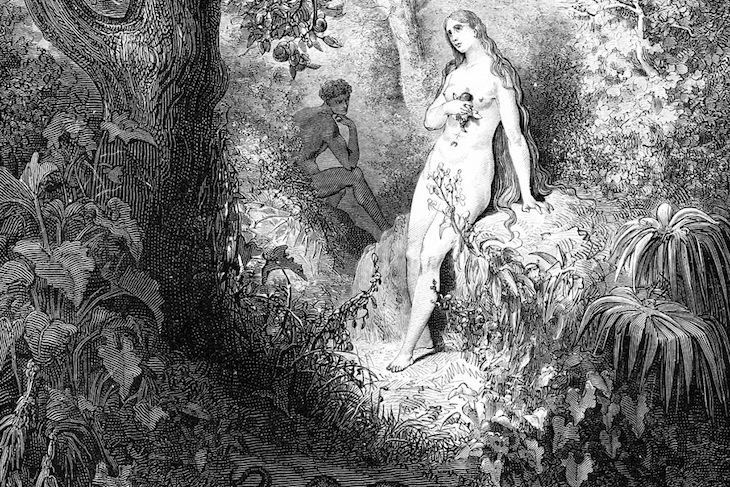

Poole’s excellent book will have its own enemies, since it reads like an implicit polemic against certain types of feminist analysis of the poem. Ever since Sandra Gilbert denounced the ‘visionary misogyny’ of Paradise Lost and its deleterious effects on generations of women readers in The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), some — but certainly not all — feminist readings have stressed its harmful role in consolidating patriarchal hierarchies. While it would be difficult ever to read Paradise Lost as a proto-feminist piece — it’s the narrator, after all, who makes the infamous case for Eve’s subordination to Adam: ‘He for God only, she for God in him’ — Poole reminds us that Milton’s networks of allusion, wordplay, and avant-garde poetics always complicate and frequently undermine the blunt misogyny of the Genesis account of the Fall (regarded by everyone in Milton’s world as being historically true). ‘There is no victory to be had’, he asserts, ‘in holding Milton responsible for this mythology.’ It’s difficult to argue with that; and in his careful reading of the effects of Milton’s reading on his greatest poem, Poole scores plenty of victories of his own.

Comments