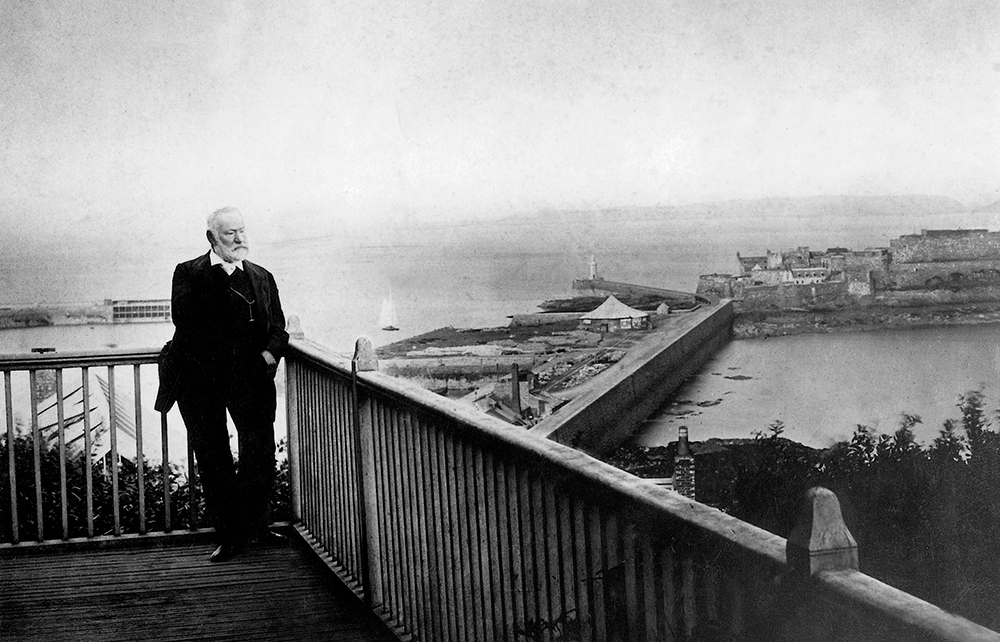

Recently I visited Hauteville House, Victor Hugo’s home on Guernsey, now magnificently restored, where he spent 15 years of exile in opposition to the autocratic regime of Napoleon III. His third-floor eyrie, a crystal cage with walls and ceilings of plate glass, resembles a greenhouse. Hugo wrote there, standing at a small, flat-topped desk, gazing out across the water at the distant coastline of France. He slept in one of two adjacent attic rooms. In the other slept a chambermaid, summoned by her master with a few light taps on the partition wall.

Vulnerable but resilient, Célina accepts the two francs left under her pillow for a night of sexual favours

The publication in the 1950s of coded entries in Hugo’s account books revealed payments for sex to a succession of serving maids. One of these was Célina Henry, the narrator of Catherine Axelrad’s novella. Published in France in 1997, the book has been translated into English by Philip Terry with some nice demotic touches.

Axelrad takes the bare facts about Célina – born into poverty on Alderney, joining the Hugo household in the late 1850s, and dying from tuberculosis in 1861 – and weaves them into a story of a vulnerable but resilient young woman who accepts the two francs left under her pillow for a night of sexual favours while eavesdropping during the day on the life taking place above stairs. Célina’s curiosity and intelligence provide her with insights about Hugo’s marriage and his relationship with the mistress he keeps down the street. She adopts the tragedy of Hugo’s family life, the drowning of his elder daughter in the Seine years earlier, as if it were her own. She grows jealous for her intimacy with Hugo when he briefly turns his attention to the local seamstress.

The extraordinary quality of Axelrad’s writing is the silence that envelops it. There is a featherweight lightness to it all that is a supreme contrast to the heavy mournfulness one feels after reaching the final page. Célina is not a submissive character, and life’s blows, including fears of impending death, glance off her, seemingly without leavinga mark. Nor is she subversive (unlike Célestine in Octave Mirbeau’s The Diary of a Chambermaid, whose employer fetishises her boots and ends up dead with one of the boots stuffed in his mouth). She knows that her social standing limits her freedom and the options open to her, and that it’s not, as one character says, ‘a crime to sleep with a servant’. Nevertheless, within those limitations, she is able to exert her individuality and choose her own lovers, including one disastrous final relationship after she leaves Guernsey.

At the end, I could almost believe that Axelrad’s Célina could have had some influence on Hugo’s creative life, perhaps as a prototype of Fantine, one of the most attractive characters in Les Misérables, forced to become a prostitute before she, too, dies from tuberculosis.

Comments