Here’s the latest in our Another Voice series of posts, which give prominence to viewpoints outside the normal Coffee House fold:

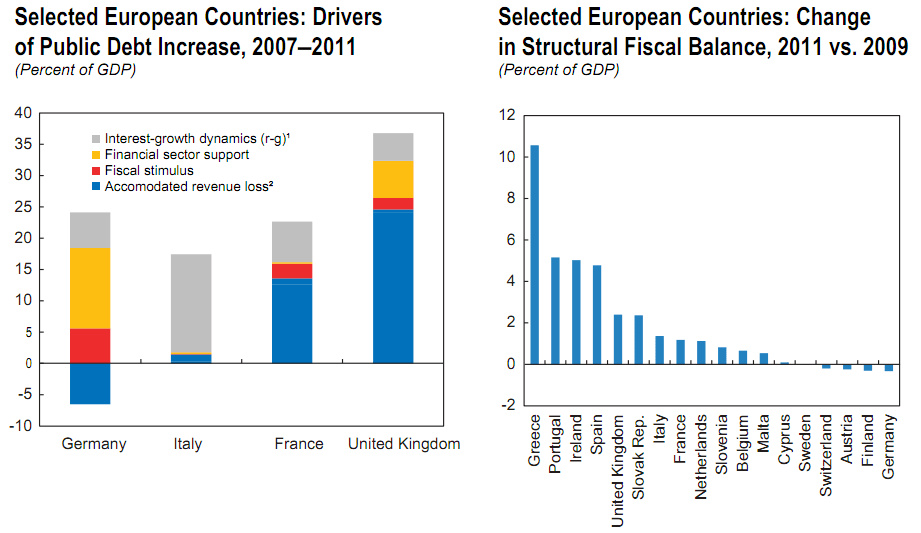

You can’t help but notice that the UK economy isn’t doing too well. Part of this is down to international developments, sure. But part – as Mervyn King said in “http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/pdf/govletter111006.pdf”>his letterto George Osborne last week – is the result of “fiscal consolidation”, aka spending cuts. The IMF’s assessment, published a few days ago, shows both why debt has risen (lower tax revenues) and what is happening now (sharp contraction):

And there’s much more contraction to come:

So why keep on contracting if it is affecting economic growth? Clearly, the Prime Minister thinks that this is exactly what is needed. Yet, in doing so, he shows that he as learnt nothing from the history of the Great Depression. That history, and conventional economic wisdom, tells us exactly what we should be doing – and it is not what Martin Wolf “http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/045aab84-e61c-11e0-960c-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Zu0ayAI7”>describes in the FT as “kamikaze tightening”. The public sector needs to support demand, not reduce it, until such time as the private sector – households and firms – again has the confidence to spend and invest.

The government’s response is that without tightening, interest rates would be rocketing upwards. But there are two problems with that argument.

The first is the implicit suggestion that low long-term interest rates are the result of “confidence” in the government’s fiscal plan. As I have “http://www.newstatesman.com/economy/2011/08/interest-rates-debt-government”>written before, this is simply nonsense. Low long-term interest rates in the UK reflect not economic confidence but its opposite – the view of financial markets that the economy is weak and getting weaker. The fall in rates has been strongly correlated with falls in UK equity markets and falls in sterling. Neither is exactly a mark of “confidence”. As Coffee House’s own Fraser Nelson puts it, “if

low borrowing costs were a precursor to economic success, Japan would have been booming long ago”.

The second problem is the claim that – while fiscal consolidation may not be driving the current low level of interest rates – a reversal would lead to such a market panic that interest rates would rise sharply anyway. With fiscal consolidation, they say, the UK is a “safe haven”; without it, we’re Greece. But comparisons of the UK to Greece miss the point. As Simon Wren-Lewis has explained, the situation of the UK is completely different:

“There is a straightforward reason why the current debt crisis is largely confined to the euro area, which can be summed up in one short statement: these countries cannot print their own currency.”

This is a fundamental point. Investors in gilts know that the UK has the power to print unlimited quantities of sterling. So the chances of them not being repaid are vanishingly small. Moreover, we have a floating exchange rate. So if foreign investors sell gilts, the pound falls; at some point it falls to a level where it becomes attractive again. So there are natural adjustment mechanisms to bring us back to equilibrium.

But these adjustment mechanisms do not apply to countries that borrow in foreign currency – as effectively is the case for the eurozone. Here, when deficits go up, investors may rationally fear default, because governments cannot print money. And the currency can’t fall to make it more attractive to invest in government bonds.

So interest rates go up, leading to increased interest payments, and higher deficits – so the risk of default further increases. A spiral towards default can develop even if, before the whole cycle started, the government was perfectly solvent.

So it doesn’t take much to tip a country from a vulnerable position into a crisis. This, arguably, is what is happening to Italy and Spain (Greece, which is clearly insolvent and has been for some time, is a rather different case). But it can’t, and won’t, happen here.

All this is set out in much more technical detail by Paul De Grauwe”http://www.econ.kuleuven.be/ew/academic/intecon/Degrauwe/PDG-papers/Discussion_papers/Governance-fragile-eurozone_s.pdf”>here.

Rather than compare ourselves with Greece, we should take more notice of Denmark — like us, outside the eurozone with their own central bank and currency. The Danes have just elected a coalition, headed by the Social Democrats, who campaigned on a platform of “more spending on schools and hospitals, policies Rasmussen [the outgoing centre-right Prime Minister] warned will jeopardise Denmark’s AAA credit rating”. Sound familiar?

And the thing is, it seems to working out okay for Denmark. Danish ten-year bond yields are hovering around the 2 per cent mark, down about half a percent over the last two months. So, they’re lower than the UK’s, and they’ve fallen faster. Danny Blanchflower has the details here.

Even the IMF seems to have woken up to this point. A year ago, the Fund bought Osborne’s position hook, line and sinker, saying (without a scrap of evidence) that, “The consolidation greatly reduces the risk of a costly loss of confidence in fiscal sustainability”. In sharp contrast, they now argue that, “if activity were to undershoot current expectations and risk a period of stagnation or contraction, countries that face historically low yields (for example, Germany and the United Kingdom) should also consider delaying some of their planned consolidation.”

What has changed? If abandoning the plan would have risked a loss of confidence then, why wouldn’t it now? After all, the medium term figures look worse, not better. The answer is that the Fund’s current position is based on economics rather than ideology.

There is a legitimate debate about the optimal pace of what is – over the medium term – a necessary fiscal consolidation in the UK. But the UK is not insolvent; it is not close to insolvent. Anybody who compares the UK to Greece is simply scaremongering, and there is no need to take them seriously.

Jonathan Portes is Director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research

Comments