There were great numbers of young men who had never been in a war and were consequently far from unwilling to join in this one.(Thucydides, 5th century BC)

I love that quote, inscribed on the walls of the Imperial War Museum, because it tells you so much both about the reason wars happen and about the nature of men. Most of us go through a phase where we think it would be terribly exciting to ‘see the elephant’. And for a lucky few, it’s everything they hoped it would be and more.

One of those lucky few is an extraordinarily jammy sod called Matthew VanDyke. By rights this young American filmmaker from Baltimore ought to be dead a thousand times over. Instead, rather more by luck than judgment, he not only survived six months in a Benghazi prison in which he could hear his neighbours being tortured to death, but also several weeks as an active combatant (for the rebel side) in the notoriously vicious and unpredictable Libyan civil war.

Since his adventures were turned into an award-winning Storyville documentary The Arabian Motorcycle Adventures (shown on BBC4 the other week, still viewable on iPlayer and highly recommended), Vandyke has come in for a lot of stick from critics for being a cold-eyed, narcissistic, irresponsible, selfish thrill-seeker who put his yearning for adventure and fame before the needs of either his loved ones or those oppressed Libyans whose cause he professed to champion. To which my response is, ‘Yeah. And?’

Indeed, it’s a criticism so utterly fatuous it’s like writing off When We Were Kings because of the insufficiently Corinthian spirit displayed in it by Muhammad Ali. Or like rejecting Man on Wire on the grounds of its being unbalanced by its hero’s monomaniacal obsession with walking across a wire strung between two high buildings. VanDyke, prominent throughout though he is, is oddly a cipher. What matters, far more, is the weird, random stuff going on around him, almost in spite of him, and what it tells us about the meaning of life in general and war in particular.

One thing it tells us is: be careful what you wish for. VanDyke was a spoilt only child with obsessive compulsive disorder, few friends, and a burning desire to become an adventurer like Lawrence of Arabia or the rugged Aussie documentary-maker Alby Mangels. So, after university, he set off on a motorbike on a 35,000 mile tour of north Africa and beyond, so terminally naive that on encountering his first hole-in-the-ground toilet he didn’t even understand what it was for.

None of this would have been of much interest to anyone had not VanDyke chronicled every last detail of his trip with an in-built helmet camera. Being OCD, he didn’t stop there. He’d drive up a hill, set up the camera, then drive back down and up the hill, often several times, in order to get the perfect shot of him driving up a hill. And so on and so forth. When genuinely exciting stuff started to happen to him, this obsessive chronicling suddenly became documentary gold.

The occasion in Iraq, for example, where he’s sharing a meal with a group of Libyan rebels he has befriended. One of them announces, jauntily but also mournfully and fatalistically: ‘Last supper’. And so, indeed, for several of those present, it proves.

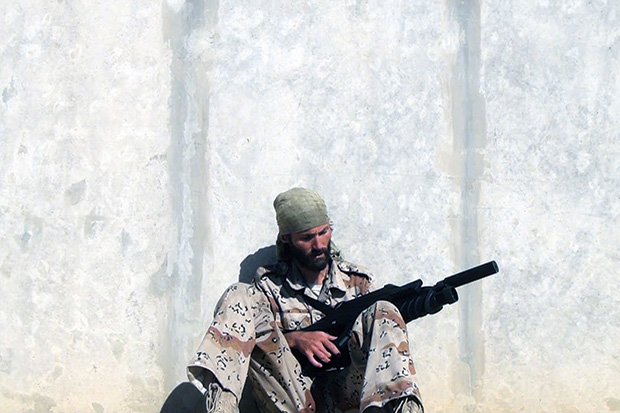

Given the circumstances, this is not exactly surprising. The sheer amateurishness of his rebel chums in the early stages of the revolution is extraordinary. They advance on Gaddafi’s well-armed forces with absolutely no military experience, in a pick-up truck they have rebuilt from scrap, with, on a mount welded to the back, a heavy machine gun that they have retrieved from the smouldering ruins of a recently bombed military base. Then they drive to the front line…

Part of the documentary’s appeal is the sheer astonishment that you experience watching VanDyke go through so much so (relatively) unscathed, and at the unlikely twists and turns of fate that make all the difference between life and hideous death. But what’s also very illuminating is the Thucydidean light it sheds on the visceral pull and perceived glamour of war, especially in the age of phone cameras and social media.

‘Everybody wants cool stuff they can show their friends on Facebook,’ says VanDyke, at one point. And this is the heart of it all. He first notices it while embedded with US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan; then, even more so, as a fighter himself in Libya in arguably the most saturatedly filmed war in history: every soldier he meets is conscious of himself as a character in a war movie — US soldiers demanding retakes of themselves kicking down doors till the scene looks right; Libyan rebels draped in bandoliers of ammo, firing heavy machine guns from the hip, fully exposed, not because it serves any practical purpose but because it makes them look just like Rambo.

It’s one of the most enthralling, constantly surprising documentaries I’ve seen in ages. Do watch.

Comments