We hear a lot about the rights of the child, but the first I heard of the child’s right to play was at the Barbican’s latest exhibition. Among the games-related facts in Francis Alÿs’s new show is a quote from Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children, confirming a child’s right ‘to engage in play and recreational activities’.

Barbie has stood seven times for the US presidency. (As a young looking 65, she could do well)

Are children’s games under threat? Alÿs thinks so. Children in Europe today, he laments, have a tenth of the freedom to roam that he enjoyed growing up in the 1960s in a Belgian countryside virtually unchanged since Bruegel. During the course of his travels in 15 countries over the past quarter-century, Alÿs has amassed a cinematic archive of children’s street games. He started in 1999 in Mexico, where he is based, with a boy kicking against the law of gravity by booting a plastic bottle uphill; since then, while filming in conflict zones, he has recorded other forms of youthful resistance. In ‘Haram Football’ (2017) boys in Mosul play a balletic form of air footie in defiance of a Isis ban on ball games; in ‘Parol’ (2023) camo-clad kids patrol the streets of Kharkiv with wooden toy guns in search of Russian spies, stopping drivers at pretend checkpoints to demand passwords, check documents and inspect car boots.

But most of the games in Alÿs’s films are much older: the two girls playing with stones on a Kathmandu stairwell in 2017 are engaged in a version of knucklebones played by royal children on a Hittite relief of 800 bc, while the bicycle tyres driven downhill by boys in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, in 2010 are the descendants of the wooden hoop rolled by the naked youth on a 500 bc red-figure drinking cup from Attica.

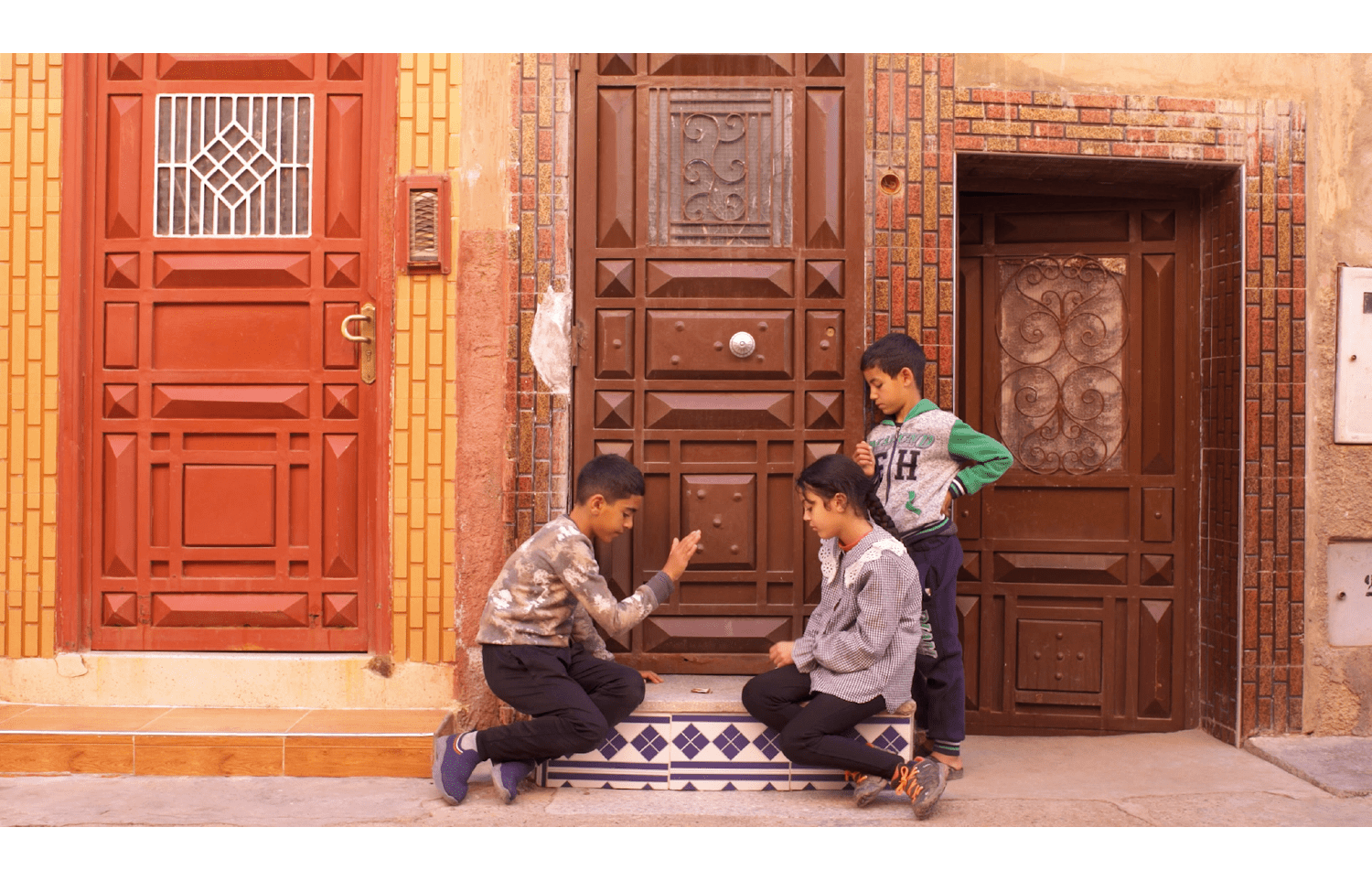

With films running back-to-back on a dozen screens, the Barbican’s lower gallery has been transformed into a cinematic playground. There are jumping games, hopping games, spinning games; boys hurtle on homemade skateboards down a steep narrow street in Havana in what looks like a luge race on tarmac. On a rainy day in Pajottenland, Belgium, children race snails with shells painted in their owners’ colours, urging them on like slithering slo-mo greyhounds; in a Congolese version of Subbuteo, players flick a marble round a dirt arena fenced with a palisade of sticks like a miniature Mad Max stockade. Such games require minimal equipment: the slap game filmed on a Moroccan doorstep (see above) involves flipping empty sweet wrappers, carefully folded. These kids have nothing, but they have fun – which brings us to a rather different exploration of children’s play across town at the Design Museum.

We’ve had Barbie the movie; this is Barbie: The Exhibition, mounted in partnership with Mattel. None of the games recorded by Alÿs, apart from Parol, involve play-acting: games with Barbie, on the other hand, are pretend play dependent on the acquisition of stuff. Stuff is, of course, what the Design Museum’s about, and this exhibition is keen to demonstrate that in her 65 years of existence, Mattel’s 11.5in plastic mannequin has been at the cutting edge of it. Since emerging from her cardboard box in 1959, Barbie – in her many and varied incarnations – has acquired the keys to at least 50 dreamhouses, furnished in the very latest taste: her current bedroom features pink plastic doll chairs designed by Philippe Starck for Italian brand Kartell. She doesn’t have a safe room yet, but that may come.

Barbie was the idea of Mattel co-founder and first president Ruth Handler, who watched her daughter Barbara dressing paper dolls and decided: ‘Little girls just want to be bigger girls.’ The company’s male executives were unconvinced that a doll with an adult woman’s body (sort of) would appeal to little girls used to playing mother to baby dolls. But ‘No. 1 Barbie’ (see below) – with her teenage ponytail, snazzy striped swimsuit and trousseau of fashionable outfits – flew off the shelves, and the rest is herstory.

Mattel has since developed walking, talking, dancing, all but living dolls including, in 1995, a version of Barbie’s kid sister Skipper with the ability to grow taller and sprout breasts if you rotated her arm – ‘a simplified version of puberty’, we’re told, that ‘offered children a reassuring take on the prospect of “growing up”’. Eek. In the meantime, Barbie has acquired friends of diverse ethnicities, while ‘boyfriend’ Ken has been demoted to a relationship that is ‘deliberately undefined, allowing children to project their own assumptions’.

There are now ‘curvy’ Barbies with fuller figures, Barbies in wheelchairs and – in contrast to the all-time best-selling Totally Hair Barbie – a totally hairless Barbie ‘reflecting the lived experiences of children with alopecia’. Barbie has been reinvented as ‘an aspirational role model for children’, progressing from early careers in nursing, teaching and cheerleading to chief executive and astrophysicist. The lookalike Barbie who joined European Space Agency astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti on the International Space Station in 2022 and was filmed beside her floating in zero gravity was on a mission to interest more girls in STEM subjects. Barbie has also stood seven times for election to the US presidency. (As a young-looking 65, she could do well in the next one.)

If ‘children’s games are an assertion of independence from the adult world’, as Alÿs believes, Barbie games are an acceptance of submission to it. In 1991, Mattel released a hip hop-inspired Rappin’ Rockin’ Barbie, but where were the accompanying tattoos and lip rings? In games with Barbie, the adults call the shots. I left the Barbican exhilarated and the Design Museum depressed, though not as doomy as string-games collector Kathleen Haddon who feared that ‘civilisation kills cat’s cradles’.

In the run-up to the exhibition, Barbican outreach teams counted 46 children’s games still in play in local school playgrounds. I’m sure such games will continue to be played long after Barbie-branded clobber has stopped tinting landfill pink. On the evidence of history – and Alÿs’s films – they have more than nine lives.

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets is at the Barbican Art Gallery until 1 September. Barbie: The Exhibition is at the Design Museum until 23 February 2025.

Comments