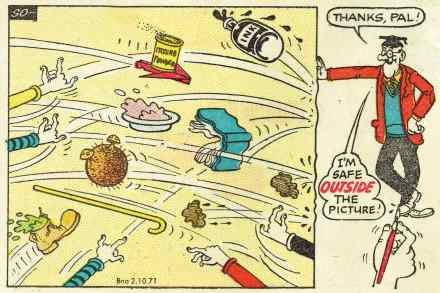

Are kids’ games under threat?

We hear a lot about the rights of the child, but the first I heard of the child’s right to play was at the Barbican’s latest exhibition. Among the games-related facts in Francis Alÿs’s new show is a quote from Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children, confirming a child’s right ‘to engage in play and recreational activities’. Barbie has stood seven times for the US presidency. (As a young looking 65, she could do well) Are children’s games under threat? Alÿs thinks so. Children in Europe today, he laments, have a tenth of the freedom to roam that he enjoyed growing up in the