There is a grim irony in today’s announcement of the commemorations marking the 80th anniversary of VE Day on 8 May – at the very time that the Western alliance is collapsing. The plans include dressing the Cenotaph in Union flags, a military procession and flypast in London and a service of remembrance and thanksgiving at Westminster Abbey, followed by a concert. All good, and all appropriate.

But, according to the government press release, ‘street parties will also be held across the country’. Really? The symmetry is obvious, of course. VE Day was one big street party as the country celebrated the defeat of the Nazis and the triumph of freedom. The events in the White House over the past few days, however, and the sudden volte face in which the US has gone from being the leader of the free world to siding with Russia, North Korea and Belarus against Ukraine in a vote at the United Nations, have changed everything. Unless the proposed street parties are meant to be a wake for the death of Nato and the dismemberment of Ukraine, is there anyone who thinks now is the time for parties to celebrate the steadfastness of democracy?

If Trump is now, at the very least, ambivalent about defending Europe, we have to change our mindset

There are many lessons we need to remember from VE Day, but the two most salient have been directly challenged by President Trump – thanks to which we now find ourselves in such dire straits. First, and most obviously, VE Day was only possible because the US stood with us and the Allies in the second world war.

Even after the Soviets joined forces with the Allies in June 1941, the key to victory was American involvement in December 1941. That was pivotal not just to victory in the war but to keeping the peace in Europe in the following decades up to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. That was, of course, through the vehicle of Nato, the greatest and most successful defensive alliance in history. In the possibly apocryphal words of Lord Ismay, Nato’s first Secretary General, it was designed to keep the Americans in, the Russians out and the Germans down.

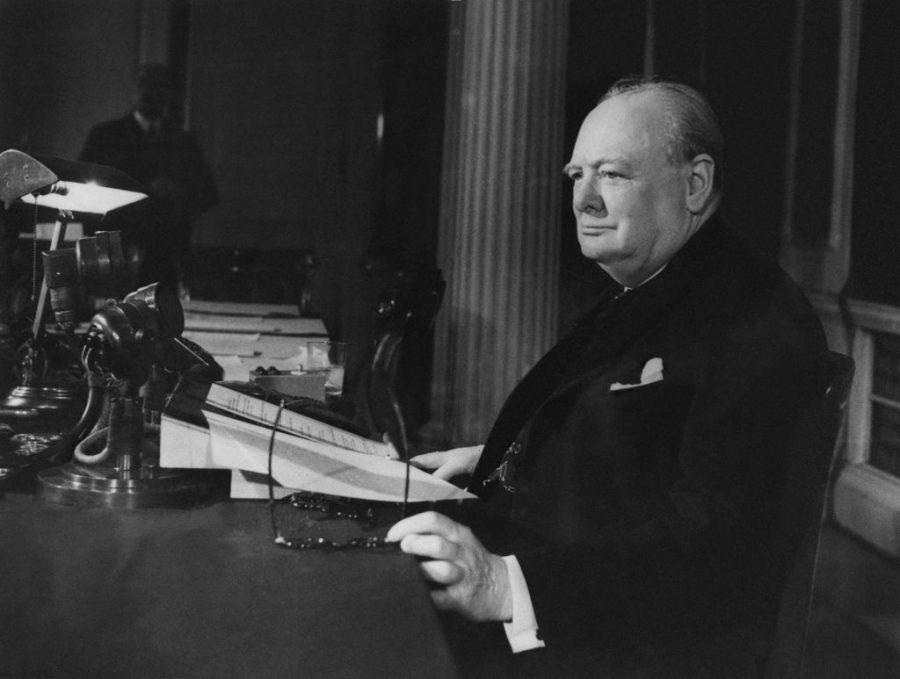

The second key lesson was learned in the 1930s – and has remained essential ever since. Weakness in the face of tyranny and aggression means defeat by tyranny and aggression. Churchill was ignored when he made that case throughout the 1930s. Chamberlain thought he could do a deal with Hitler – a phrase with distinct echoes today.

Parallels with the 1930s are, of course, inexact, and the revisionist case for the Munich agreement is that it actually bought time for rearmament so that, by the time war was declared in September 1939, defence spending had risen from 2.5 per cent of GDP (a familiar figure) to 7 per cent. But true as that is, the echoes of Munich are eerie. In September 1938, Czechoslovakia was carved up without it having any say in the arrangement, after the UK, France and Italy agreed with Hitler that the country must surrender its border regions (the Sudetenland) to Germany. Do I need to spell out what Trump is proposing to do to Ukraine with Putin?

Hitler observed that when pushed around, his enemies would speak loudly but do nothing, and that led directly to the invasion of Poland in September 1939. Leap forward to 2013 and Obama’s supposed ‘red line’ for Assad, saying that if the Syrian leader used chemical weapons on his own people he would act. After David Cameron lost a Commons vote on the use of force (thanks to then Labour leader Ed Miliband whipping his MPs to vote against), Obama ran scared of Congress and did nothing.

Assad’s main backer, Putin, drew the correct conclusion that the West was fundamentally weak. This was a conclusion he had already drawn in 2008 after his invasion of Georgia was met with no response, and after witnessing the US pull out of Afghanistan from 2020. That conclusion was tested successfully also in 2014 when Putin invaded Crimea, with no serious response, which led to his calculation that he could launch a full invasion of the country in 2022.

The Ukrainians have fought with far more bravery and success than Putin expected. But while the US and Europe did at least help with military aid, our response – even before Trump – was too little. We gave ludicrous caveats on the use of weapons and equipment on the limited amount we did supply. It also came too late – coming after the invasion, rather than giving serious defensive capability before it to act as a deterrent.

That word is the key. Hitler was able to march through Europe because we were unable – and unwilling – to deter him. Putin decided he could invade Ukraine because we were unable and unwilling to deter him.

There does seem to have been a realisation across much of Europe that if Trump should now be regarded as, at the very least, ambivalent about defending Europe, we have to change our mindset. And while it’s true that for the UK increasing defence spending by 0.2 per cent to 2.5 per cent of GDP isn’t even close to being enough, and a commitment to 3 per cent in the next parliament is paltry in the circumstances, that misses the point. The entire debate has changed. The issue now is how much more and by when spending must increase.

That is why VE Day remains of immediate and pressing relevance. We know from the second world war that if Putin is able to walk away with Ukrainian territory that he has grabbed by force, and that we have offered nothing but angry words in response, the die will be cast for the Baltics, Poland, and anywhere else. We have to be able to deter Russia. We have to do what we did not do in the 1930s.

Comments