In 1930 Evelyn Waugh, already at 27 a famous novelist, spent two days in Barcelona. He came upon one of the art nouveau houses designed by Antonio Gaudí, who had died four years earlier. Waugh was captivated by the swooshing ‘whiplash’ lines of the building. He hired a taxi and asked the driver to take him to any other buildings in the same style. So he saw a number of Gaudí’s fantastical creations, including his church (often mistakenly called a cathedral), La Sagrada Familia. It took an extra-ordinary leap of taste for Waugh to admire this flamboyant architecture at the height of the Modern Movement, with its insistence on ‘clean lines’ and ‘form follows function’.

More than 20 years after Waugh was in Barcelona, I had a similar epiphany, aged 12, on a visit to Paris with a school party. I suddenly encountered one of the strange, tendril-like Métro entrances (c.1900) by Hector Guimard. I had never heard of him or the art nouveau style, but I was mesmerised by the exotic ironwork: it seemed incredible that a municipality had officially sanctioned such work.

Ten years after my Paris visit, the great art nouveau revival burst upon London, with exhibitions at the Victoria & Albert Museum of Aubrey Beardsley and the Moravian-born poster artist Alphonse Mucha and pioneering books by Robert Schmutzler, Maurice Rheims and Mario Amaya, the art critic later shot by a madwoman with Andy Warhol. (Schmutzler’s book was translated into English by Edouard Roditi, who in his Oxford days had been described by Sandy Lindsay, the left-wing Master of Balliol, as ‘the second Harold Acton and the third Oscar Wilde’.)

Nouveau was the dominant revival style of the 1960s. It influenced the mind-expanding ‘psychedelic’ art of the drug culture and was one of the main ingredients of Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba ventures. Collectors grappled for René Lalique jewellery, Tiffany glass, and furniture by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Nearly half a century on from that splurge of nouveau, it is time for a new appraisal, and in Norbert Wolf’s mouth-watering book Art Nouveau (Prestel, £50), it gets the works. It is a superbly selected and produced anthology of the style — a very grand and heavy volume, a work of art in itself. The old favourites are here, with one of Mucha’s best posters as frontispiece, exquisite Lalique brooches and Mackintosh furniture.

The publisher’s blurb asserts: ‘This book offers a sumptuous tour of art nouveau, one of the most popular of all art epochs and one that has continued to exert an undiminished fascination to the present day.’ Well, there was a bit of a dip as art deco supplanted nouveau, but the claim is essentially a just one. It is also true — according to the blurb again —that Wolf devotes space to areas that have so far received little attention, such as nouveau’s innovative aesthetics of light. It is hard to convey how glorious the whole confection is. It really is worth £50.

When Fiona MacCarthy’s biography of Edward Burne-Jones was published this year, in succession to her 1994 life of William Morris, I thought: ‘Bet she tackles Dante Gabriel Rossetti next.’ I was wrong. MacCarthy is turning her formidable attentions to the Bauhaus’s mastermind, Gropius.

Bad luck, Rossetti — but luckily the cavalry have appeared on the horizon in the shape of J. B. Bullen’s excellent study, Rossetti: Painter and Poet (Frances Lincoln, £35). Admirable as MacCarthy’s Burne-Jones is, it is rather cheese-paring (or frieze-paring) in illustrations. Bullen’s book is not, and that is a big plus, since Rossetti is, after Michelangelo, one of the few creators distinguished both as artist and poet. (I suppose one has to count William Blake; but though I think him a great poet, I have always regarded him, as an artist, as the village idiot of neo-classicism.)

In addition to his dual talents, Rossetti also had a wild love-life, as the recent television series on the Pre-Raphaelites demonstrated. I mean, all that stuff about digging up his dead wife Lizzie to retrieve the poems he had buried with her: beat that for Gothic behaviour.

Bullen, who is Professor Emeritus of the University of Reading, is a remarkably good writer. Of the women in Rossetti’s paintings, he writes:

They have voluptuous red lips, long, enervated hands, and soulful, yearning expressions. Their hypnotic eyes peer from under dark, cascading hair. Their bodies are luxurious and languid.

Throughout the book he quotes Rossetti’s poems, among them the drowsily loving one that begins, ‘Your hands lie open in the long, fresh grass’ — which in the Edwardian period was converted into a sensitively matching song that I’d like to hear sung by Ian Bostridge.

I was a friend of Frances Lincoln, whose firm publishes Rossetti. Sadly, she died about ten years ago. When I first knew her in the late 1960s, she was a junior editor at Studio Vista, and a quiet, retiring young woman. I must admit I had her down as a backroom girl, the equivalent of what business moguls call ‘the unpromotable bright boy’. How wrong I was: setting up her own firm, she showed discrimination in her authors and a steely determination in getting from them what she wanted.

I think she would have been proud not only of Rossetti but of her firm’s Roberto Polo: The Eye (£95) by Werner Adriaenssens and six others. The price is bound to deter many; but they will be missing a huge treat. This book is the equivalent of the Renaissance German Wunderkammer, cabinet of marvels. The full-page illustrations show over 300 masterpieces and gemstones from Polo’s extraordinary collections. He is 60, lives in Brussels and is himself an artist. He is also an entrepreneur, having founded Citibank’s fine art investment services. ‘Vision,’ he declares, ‘is the art of seeing what is invisible to others.’

To buy his book is to acquire one’s own private museum. The collection is strong in opulent 18th-century French works, 19th-century Belgian ones and art nouveau, but also extends into adventurous modernism. (Another of Polo’s dicta: ‘The avant-garde exists only when it is rejected’).

In the jacket blurb is a sentence that made me want to investigate a little:

In 1988 … he became the victim of a Kafkaesque judicial affair from which he arose in 1995, according to the New York Times, as ‘the wonderful phoenix of the art market’.

Behind this euphemistic piece of PR is the cold fact that Polo is a convicted criminal. In 1988 13 of his clients accused him of misappropriating $120m and failing to obtain their permission to invest in works of art, also of instigating his staff to destroy financial records. The mint Polo had made had a hole in it. He exchanged his Manhattan apartment and his five-storey Paris townhouse littered with Marie Antoinette furniture for a 14th-century cell in Lucca. Later he was in jail in Geneva. Some of his clients had faith in him after his release and the ‘phoenix’ has clearly made good — the publishers confirmed to me that this book is subsidised.

•••

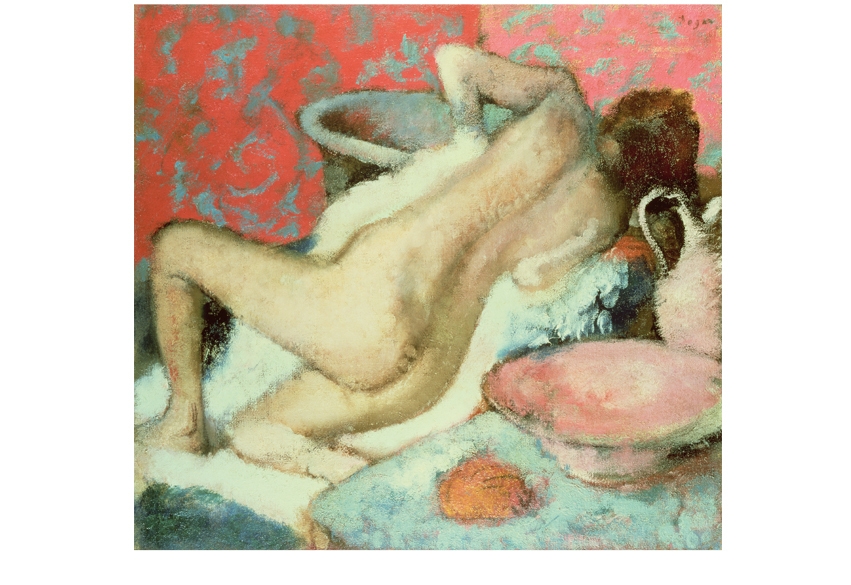

Degas and the Nude by George T.M. Shackelford and Xavier Rey (Thames & Hudson, £42) is the book of an exhibition of that title organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. It is finely illustrated and the essays in it are thought-provoking, with new insights into this supreme master’s work. But the most enjoyable and in many ways most penetrating part of the book is an interview about Degas with the late Lucian Freud by Martin Gayford, You don’t have to be a great artist to be a great critic, but it is usually valuable to know what one master thinks about another, even in the following preposterous exchange:

MG Some of the masters Degas copied would not be to your taste, I should think. Botticelli’s work, for instance, I shouldn’t think you admire.LF No, it’s sickening.

Away from that bizarre opinion, Freud — himself a particularly gifted draughtsman — notes that Degas learned from Ingres, whom Freud regarded as one of the few great painters who were also great draughtsmen — others being Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Degas himself.

MG What makes a great draughtsman?LF You could say a sense of form, but that’s not really an answer. I’m tempted to give a very annoying response: they make great drawings. I think you can tell from just a few lines whether someone can do it. I feel you would know whether somebody could draw or not from any mark they made, even from a footprint.

Degas could do it, all right. Someone who couldn’t was Picasso. His painting of his lover Fernande Olivier is reproduced on the frail pretext that she had met Degas in his studio in 1904. She didn’t become a model for Degas, but if you want to see the difference between cack-handed ineptitude and palpable genius, just turn your eyes from the Picasso, with its ungainly distortion of Olivier’s (probably quite attractive) body and his squinty rendering of her face, and look at Degas’s ‘Woman Drying Herself’ on the facing page. It was painted just a year before the Picasso, in 1905. I cannot understand the reverence in which every last scribble of Picasso is held. Evelyn Waugh, with his acutely developed taste and his own skill as a draughtsman, abominated Picasso; and Paul Johnson, another accomplished draughtsman, has written a book entitled To Hell with Picasso — my sentiment exactly. Picasso is a religion badly in need of a Richard Dawkins.

Constance C. McPhee and Nadine M. Grenstein make a bad career move in their Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine (Yale, £30) in not including my 1970 book Cartoons and Caricatures among the 231 books listed in their bibliography. Of course I am not so petty as to penalise them for that; but the omission is symptomatic of the book’s main flaw. The authors are both curators in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. They are hopelessly unclued-up about British caricaturists. Sure, they have heard of Gillray and Cruikshank; but no Sir John Tenniel; no Harry Furniss; no Linley Sambourne; no Bateman; no Fougasse; no Vicky; no Low; no Ronald Searle; no Trog (Wally Fawkes); no Larry; no Marc (Mark Boxer); no Willie Rushton; no Gerald Scarfe or Peter Brookes.

In the index we find ‘Punch (puppet)’ but no Punch magazine (or Private Eye). The ‘Levine’ in the book’s title is the competent but rather pedestrian American David Levine, whose cross-hatching technique, ironically, was closely based on that of the unmentioned Tenniel, an infinitely greater artist. The omission of Low deprives the authors of the chance to quote what one woman wrote to him, enraged by a political cartoon: ‘You are so Low, you will have to go to Hell in a balloon.’

All that said, it is a nicely produced book; and the last laugh is on the English — a devastatingly satirical caricature after Gustave Doré of ‘Un Anglais à Mabille’ — an arrogant-looking swell with Dundreary whiskers and goofy teeth.

Comments