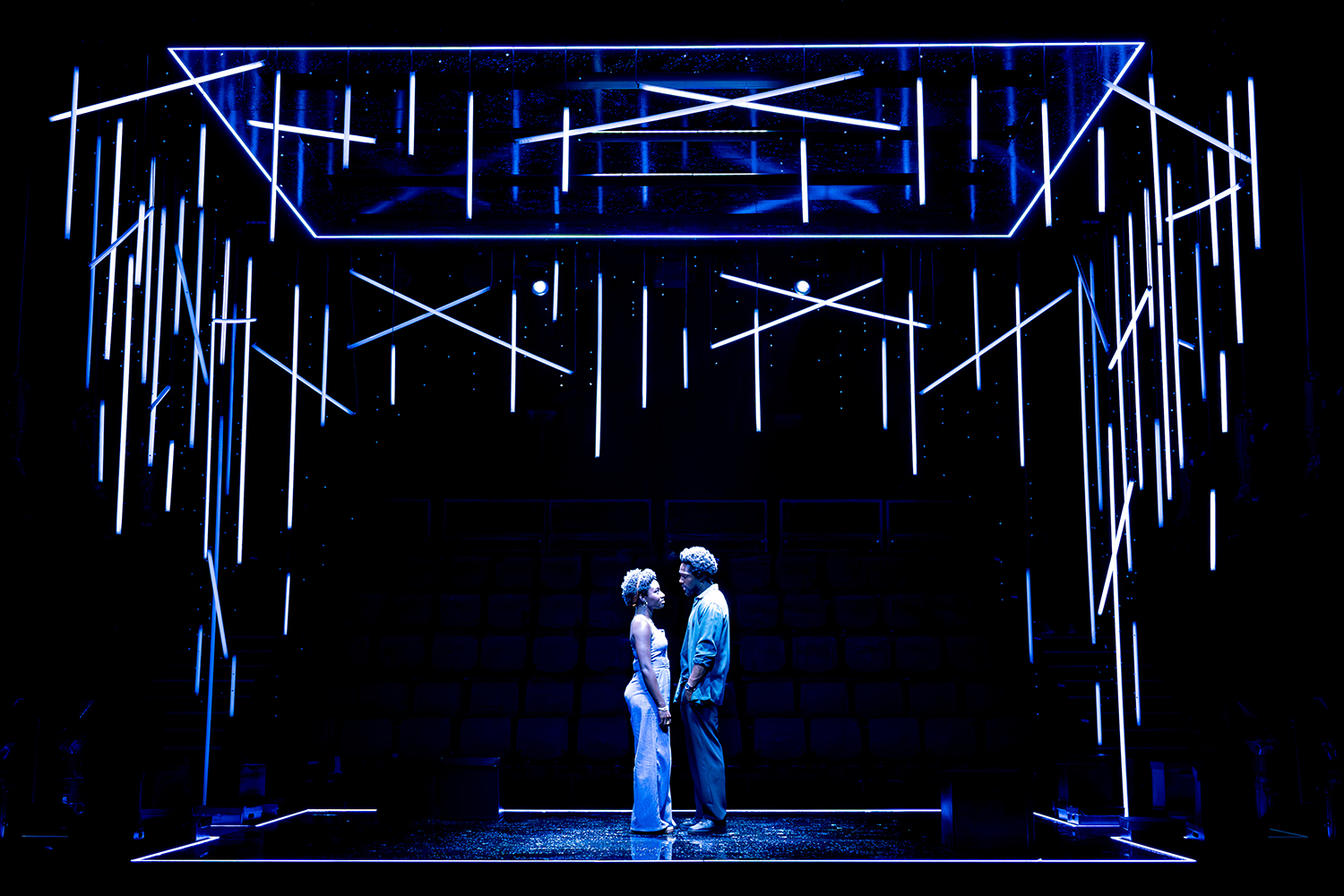

Shifters has transferred to the West End from the Bush Theatre. It opens at a granny’s funeral attended by the grief-stricken Dre, aged 32. Dre was raised by his ‘Nana’ as he calls her – rhyming it with ‘spanner’ – and he weeps when he realises that his mother has failed to show up. A beautiful young woman arrives unexpectedly. This is Dre’s teenage sweetheart and they exchange gossip over a glass of whisky while rummaging through Nana’s belongings.

The press night crowd adored these flawless yuppies. An artistic embarrassment but a sure-fire hit

The lovebirds met at school where they studied philosophy and outshone all their rivals in the class. After a short relationship they drifted apart during their twenties and now, in their early thirties, they’re ready to settle down. Will they get married? Well, let’s think. The girl’s name is Destiny so it seems possible. Both characters break the fourth wall and share confidences with the audience about their remarkable lives.

At the age of 15, Destiny was appalled by boys who treated her as ‘a grown woman’ and she withdrew into her shell and began to paint. Success arrived overnight and she became an artist of global renown whose masterpieces were exhibited in Prague, Venice and New York. Just like that. She didn’t even go to art college, apparently. Dre’s ascent was nearly as swift. After leaving school he took low-paid jobs in kitchens while working towards a diploma in business studies. He then opened a brand new fusion restaurant and the enterprise succeeded instantly. Not a single blip along the way, it seems.

Neither of them collected any debt, either. Nor were they troubled by school bullies, racist police, drug dealers, mental-health disorders or any of the woes that afflict so many characters in modern plays. Lucky them. But dramatically they’re hard to engage with because they lack internal struggles and face no serious impediments to their marriage.

Dre is a paragon of virtue. He’s tall, handsome, well-spoken and stylishly dressed in casual streetwear, like a model. Emotionally, he seems to have matured early. He works hard, he’s devoted to his family and he’s a loyal, sensitive, amusing and generous companion. But he has one vice: he’s reluctant to express his love for Destiny with sufficient lyricism and intensity and whenever she notices this fault she pulls him up on it sharply and he responds by telling her how adorable she is.

Destiny also harbours a terrible secret. She’s a perfectionist. But don’t worry: the good news is that she’s getting help for this awful problem from her therapist. These squeaky-clean lovers seem like characters from a Barbara Cartland novel. And instead of engaging in normal conversation they exchange saccharine truisms. ‘Maybe the world has to end before life begins,’ says one of them. ‘You deserve love. Big, epic love,’ says the other. The press-night crowd adored these flawless yuppies and whooped with delight as the romance developed. By the end, there were cries of ‘oooh’ and ‘ahh’ every time the lovers held hands or stroked the other’s cheek. An artistic embarrassment but a sure-fire hit.

The 39 Steps is back. John Buchan’s novel from 1915 was filmed by Hitchcock in 1935 and this show, adapted by actor, playwright and comedian Patrick Barlow, parodies the classic movie.

The story feels like an early version of a James Bond yarn and it opens with an overdressed womaniser, Richard Hannay, lounging around in his London club wondering how to amuse himself. Adventure arrives in the shape of a German seductress who claims that foreign spies are trying to kill her. They spend the night together in Hannay’s bachelor-pad where the seductress is knifed to death by an unknown intruder. Hannay is forced to escape while disguised as a milkman.

This sets him off on a wild caper across the Scottish moors, where he meets a friendly landowner who promptly betrays him. Hannay is then rescued by a helpful crofter who also betrays him. The cycle continues. Each new saviour turns out to be a crook in disguise who passes Hannay on to the next set of baddies.

The predictability of the narrative is offset by clever lighting effects and silly costume-changes that mock the creaky gothic atmosphere of Hitchcock’s original. Some of the props are badly made on purpose and when they fall to pieces, the actors roll their eyes and shrug cynically. But why satirise an elderly movie that retells a thriller written 109 years ago? Weak targets make for weak parody.

The production first opened in 2005 and its visual tricks have since been copied elsewhere, most notably by The Play That Goes Wrong. Sadly this show feels like an imitation of its imitators. It will delight anyone who likes the idea of a West End play but doesn’t want to squander too much mental energy. In other words, it’s a two-hour sleeping draft. Nothing wrong with that.

Comments