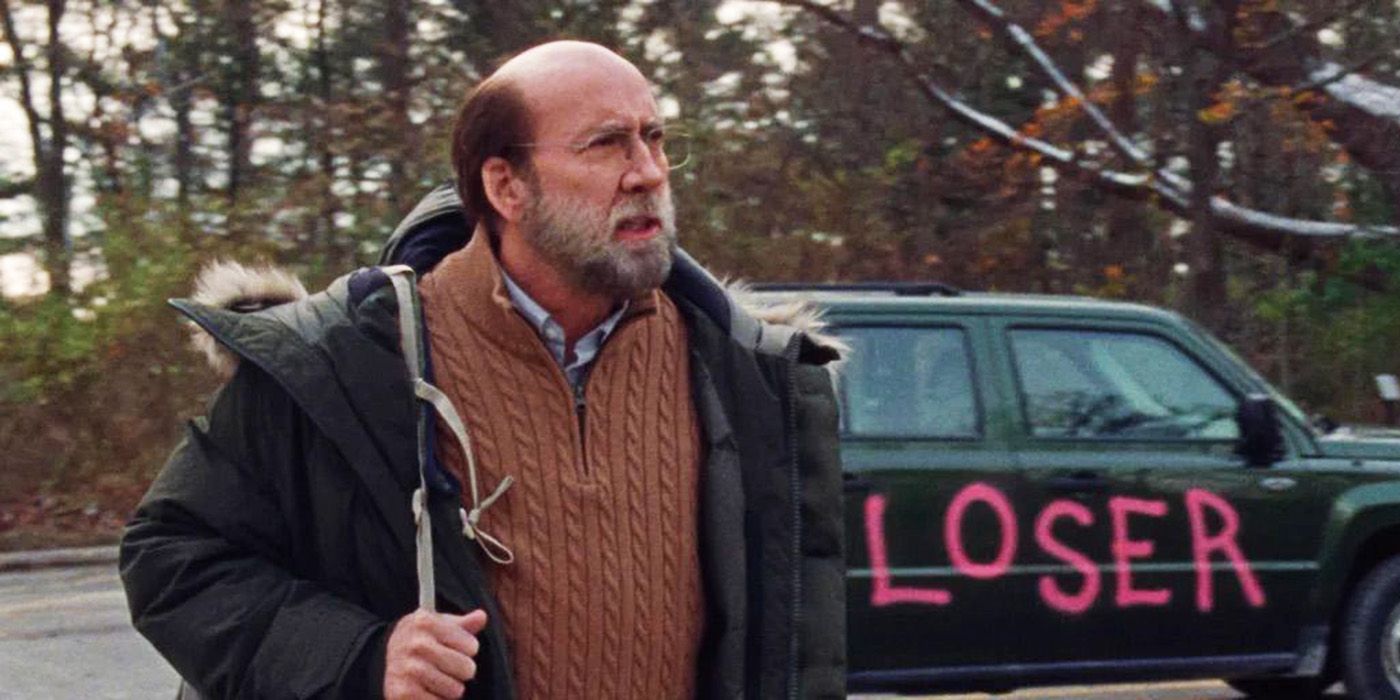

Dream Scenario is a film about modern celebrity culture and the terror of losing yourself to the internet’s virtual mob. It’s the story of evolutionary biology professor Paul Matthews, a balding, befuddled, bespectacled everyman who is the walking embodiment of anonymity – played by Nicholas Cage, the face that launched a thousand memes. At the start of the film, he gives a lecture on how zebras have adapted to avoid the mortal danger of standing out from the herd. Suddenly, in a supernatural, psychopathological epidemic, anorak-clad Paul finds himself appearing in everyone’s dreams. At first, he is just a benign bystander; in one dream, he stands there admiring a mushroom while his student is stabbed by a serial killer.

Paul, like so many of us, uses his smartphone stardom to prove he is not tragically ordinary

Paul wholeheartedly welcomes the newfound attention and adoration that comes with being an overnight sensation and there are some agonising scenes where he meets with millennial marketers who want him to do deals with Sprite and Obama. However, dream Paul soon turns violent; he starts torturing, raping and murdering people in their nightmares, and real Paul in turn loses his job, his home and his family.

The film, which is less of a comedy and more of a slowly curdling cringefest, satirises everything from cognitive behavioural therapy to apology videos to targeted advertising – what if dreams could be used as the perfect product placements? Ultimately though, Paul’s arc of phenomenon turned pariah is a parable about cancel culture: Paul hasn’t really done anything to anyone personally, but he is nonetheless held accountable for his actions in people’s dreams.

There are obvious parallels with the real-life case of Bret Weinstein, an evolutionary biology professor who resigned in 2017 after allegations of racism were made against him. He had privately objected to white students being asked to leave campus in the name of social justice. Weinstein has since appeared on podcasts with Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson, both of whom get mentions in the film. Although there are some pretty heavy-handed takedowns of Gen-Z buzzwords like ‘trauma’, ‘lived experience’ and ‘respecting boundaries’, the film looks at the conflict between actual harm and perceived harm and how the latter has seemingly come to dominate universities in their quest for ‘safe spaces’.

Yet what complicates this supposedly straightforward criticism of cancel culture is that the film is unclear about how much we are supposed to sympathise with Paul as a victim. On the one hand, watching the fickleness of fame and the demolition of Paul’s dignity is not pleasant. He leverages his newfound popularity to get dinner party invites and his book on ants published, but aside from an agonisingly awkward sexual encounter with a fan (possibly the most nightmarish scene in the whole film), Paul never technically does anything ‘wrong’.

On the other hand, the film presents him as fundamentally insecure, and his whining inflections, delusions of grandeur and petty vanities are summed up by his wife as his ‘assholeness’. His craving for viral validation first manifests when an interviewer asks him why he thinks this is all happening, and he replies, ‘I’m special, I guess’. Paul, like so many of us, uses his smartphone stardom to prove he is not tragically ordinary. Does this not speak to so much of our modern experience? That people are willing to believe in anything – horoscopes, mental health diagnoses, the glamorous promise of being an influencer – if it means we can stand out?

The film is also ambiguous about whether Paul should apologise for his imagined behaviour in other’s dreams. At first, he refuses, despite the damage inflicted on his wife and children. His refusal to be intimidated might seem heroic, but it doesn’t make him a hero; the only way to make the madness stop is for Paul to put his head back below the parapet. As soon as he disappears from public life, he also disappears from the public consciousness. It’s therefore unclear whether the film ultimately criticises the way online activists exile anyone they deem vaguely problematic or whether it suggests that notoriety is always, to some extent, self-inflicted because we all crave exposure.

Perhaps the film’s lack of substantive commentary is not a problem after all, perhaps it’s the point. Despite what those who indulge in cancel culture might think, there is no binary right or wrong framework here. Instead, the film’s surreal style, where dream sequences are juxtaposed with horror references and silly, absurd dialogue, leans into the lunacy of it all. It’s morally messy, hysterical and fleeting, but then again so is cancel culture. Somehow we must all try to find meaning in the nonsense.

Comments