It is hardly a profound observation to say that the government has not functioned as well as it might have done for the past few months. Yet there is one important exception to the general picture of confused and counterproductive activity. Britain, for the first time in years, is developing a logical and — to use the words of Robin Cook — an ethical foreign policy.

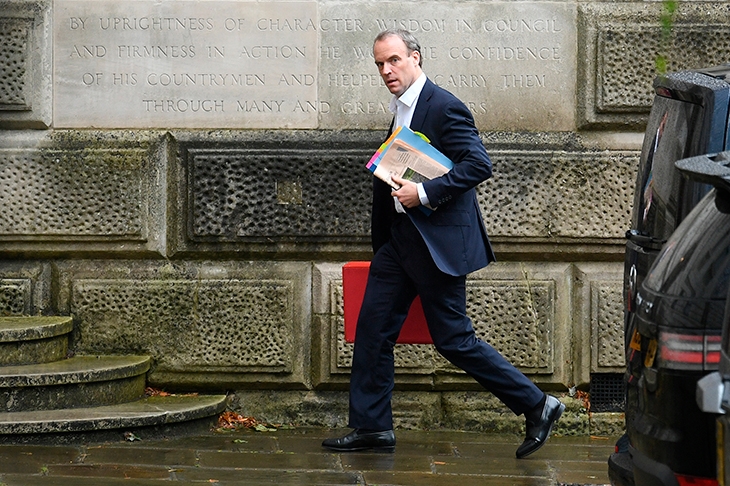

In the Commons this week, the Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab, listed the first 49 individuals to fall foul of Britain’s ‘Magnitsky law’ — a provision to freeze the assets of, and impose travel bans on, foreign citizens who have been implicated in human rights abuses. It is popularly named after a similar law passed by Barack Obama in 2012 to target Russian officials involved in the prosecution of Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian tax official who died in prison after daring to investigate corrupt public figures.

Our post-Brexit foreign policy is showing a different, more positive side to Britain

Among those named by Raab is Ahmed Hassan Mohammed Al Asiri, deputy head of Saudi Arabia’s intelligence services, which has been held responsible for the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey two years ago. There are two senior Burmese generals linked to the suppression of the Rohingya Muslims; a pair of North Korean officials who run a network of secret prisons; and 25 Russian officials, including Moscow’s chief prosecutor, Alexander Bastrykin. For once, the government cannot be criticised for turning a blind eye to countries where we have an overriding economic interest: the inclusion of Saudi officials shows that our Magnitsky law will be used as much against countries which are generally considered friendly as against hostile regimes.

When you consider the world’s numerous rogues and abusers of power, Raab’s naming of this group is a small token. But it sends an important signal that Britain is no longer going to act as a haven or wittingly aid and abet those who abuse human rights. It is remarkable that it has taken so long for a UK government to take such a stand; indeed it is 23 years since Cook boasted of his ethical foreign policy. In the meantime, Britain has sadly acquired a reputation for, albeit unintentionally, providing logistical support to the world’s criminals and tyrants. No longer, Raab told the Commons, will the henchmen of dictators ‘be free to waltz into this country to buy up property on the King’s Road, to do their Christmas shopping in Knightsbridge or frankly to siphon dirty money through British banks or other financial institutions’. It was an admission that, yes, some of the world’s most evil individuals have been free to do these things.

Why has Britain, which still enjoys in many parts of the world a reputation for decency and the rule of law, allowed itself to be used in such a way? For decades it has been all too easy for UK governments to contract out foreign policy to the EU. When sanctions have been imposed, they have tended to be part of an EU-wide initiative. While we have been part of sanctions packages against, for example, Iran, we have lacked the mechanisms for dealing with individuals who have been responsible for doing dirty work on behalf of despots.

In leaving the EU, we have forced ourselves to consider these issues afresh, and in Raab we have a foreign secretary who is not shy to make a stand. It is promising, too, that the government is revisiting its decision to allow Chinese telecoms firm Huawei to build parts of Britain’s 5G network. More-over, the government has affirmed its responsibilities towards British passport-holders in Hong Kong by offering them greater residency rights in Britain and a path to citizenship. The fact that China has responded by threatening to impose trade sanctions against Britain underlines what many have been saying all along: to China, trade with and investment in Britain by state-linked companies is not merely a commercial arrangement — it is part of a strategic policy.

Another positive development is that the Department for International Development (DfID) is to be abolished and its functions taken over by the Foreign Office. The Prime Minister has been slated, including by some of his own MPs, for supposedly showing callousness towards the world’s poor and for undermining Britain’s soft power. Yet Boris Johnson has not cut the foreign aid budget; what he has done is to ensure that in future, aid spending will be much more aligned with Britain’s foreign policy, rather than dispensed at whim. Surely, when you are handing out large quantities of taxpayers’ money to countries run by questionable regimes, it is not wrong to link it to foreign policy objectives — to make aid payments, for example, dependent on political reform. As a result of DfID’s abolition we are likely to see rather fewer handouts for Ethiopian girl bands and rather more targeted help for countries that are prepared to make a transition to democracy and to observe human rights.

Britain has not emerged terribly well from the Covid-19 crisis. Our plans for tackling a pandemic have been found wanting. We have shown neither international leadership nor managed successfully to control the outbreak within our national borders. But our post-Brexit foreign policy is showing a different, more positive side to Britain. It is showing that we are prepared to take a lead on human rights, and that we will not allow financial interests to obscure that.

Comments