A book which opens in the bushes of a Venetian garden and ends, more or less, in the cafés of Parma with chocolate panettone and biscotti dipped in coffee knows how to command attention. Given that what unfolds between these sensory episodes is densely constructed and formidable in scope, this is just as well: Peter Conrad writes engagingly and lures his reader into a grand game of cultural chess. There is no winner or loser, but we need to be alert for fear of missing a wry connection or a devilishly clever move.

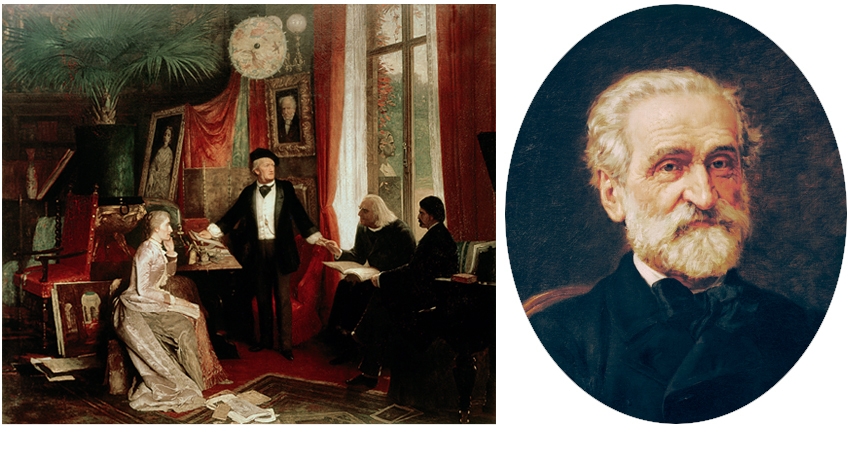

The oddity of the title hints at the awkwardness of the subject matter. Verdi and/or Wagner reflects our habit of pitting these two composers, one Italian, one German, both born in 1813 and dominating the entire century with their operatic achievements, against each other. They never met. Inevitably, however, by well-honed competitive instinct if not via gossipy publishers or press reports, they sensed each other’s every triumph and failure, often battling in ‘oblique dispute’, as Conrad terms it.

Verdi is the easier to love, the benevolent friend and comforter you are always happy to encounter, if irascible at times. From the outset, he was a hero of the Italian people. His first success, Nabucco (1842), provided them with a hum-along patriotic lament: Va, Pensiero, the Chorus of Hebrew Slaves, may have been about Jewish exile and Babylonian revenge but it soon became a cry of grief for Italy’s as yet uncreated homeland. The Risorgimento was at once the background and foreground to Verdi’s life.

In contrast, Wagner, the grotesque egotist forever involved in vendettas and grandiose schemes, the romantic revolutionary, is in all respects noisier, wilder and more iconoclastic. You may prefer Verdi’s Don Carlo or Falstaff, but Wagner’s Ring or Parsifal or Tristan are on a different scale of epic intensity. Despite best efforts to shut the door on Wagner, he sneaks into your psyche, spreads himself around and refuses to leave.

Much of Conrad’s focus is on the nature of the two men: their physicality, sexuality, politics, friendships, taste in food, attitude towards money. The composer of Rigoletto dressed soberly, without fuss; the inventor of the leitmotif instead favoured sensuous silks and velvets. Cosima Wagner revered her husband as a god. Verdi’s wife Strepponi loved hers for his humanity. Verdi ‘tabulated the sums he had earned in the hope of reaching the fabled total of a million’, whereas Wagner ‘despised and disbelieved’ in money, while also ‘demanding inordinate supplies of it’ from his patron, ‘Mad’ King Ludwig.

In its paragraph-by-paragraph comparisons, this thick book is a juggling act of great dexterity which rewards leisurely reading. Conrad’s knowledge is encyclopaedic, his anecdotes delicious. Whoever knew that Wagner had an American dentist? Every page is a cabinet of curiosities. The book has a good index and lively illustrations, but no footnotes or bibliography, which tells you much. It is a work of passion, not a thesis.

Having been an English literature don at Oxford for many years, the author is occasionally dismissed — notably in his ambitious study of the meaning of opera, A Song of Love and Death — as being too ‘literary’. For some reason this is thought, at least by musicologists rather than by opera lovers, to be a bad thing. Yet in truth his response to opera’s quixotic combination of music and drama is visceral and comprehensible.

Hundreds of books exist on the technical aspects of Verdi and Wagner’s operas. Treat this is as a long and luxurious journey across 19th-century musical Europe. Travel with a mechanic if you must. Not all good drivers like to put their head under the bonnet. Conrad, an erudite guide, is telling us to gaze out of the window at the generous and unexpected landscape he has created.

Comments