The historic centre of Bruges has 16 museums, enough to cater for every touristic taste. There’s a Diamond Museum, a Lace Centre, a Choco-Story (the narrative element distinguishes it from the 50 chocolate shops) and a Friet Museum — or ‘Belgian Fries Museum’, for English-speakers under the misapprehension that fries are French. But the main focus of the city’s five-yearly festival, now in full swing, is on a local product the French cannot lay claim to: the Flemish painting tradition founded by Jan van Eyck, who died in Bruges in 1441.

The historic centre of Bruges has 16 museums, enough to cater for every touristic taste. There’s a Diamond Museum, a Lace Centre, a Choco-Story (the narrative element distinguishes it from the 50 chocolate shops) and a Friet Museum — or ‘Belgian Fries Museum’, for English-speakers under the misapprehension that fries are French. But the main focus of the city’s five-yearly festival, now in full swing, is on a local product the French cannot lay claim to: the Flemish painting tradition founded by Jan van Eyck, who died in Bruges in 1441.

This year’s event, on the theme of Bruges Central, aims to put the city back at the heart of northern Europe — a position it ceded to Antwerp in the late-15th century when its connection to the sea silted up. At the Groeningemuseum, the major exhibition Van Eyck to Dürer: the Flemish Primitives and Central Europe 1430–1530 examines the impact of Flemish painting on the art of Germany and all points east, from Aachen to Warsaw. At the same time, the city has invited Belgium’s most famous living painter, Luc Tuymans, to curate a parallel exhibition of post-1940s work by 40 artists from former Eastern Bloc countries. Spread across five venues like a mini-biennale, Tuymans’s The Reality of the Lowest Rank: A Vision of Cenral Europe is a deliberately anti-populist gruel-fest. Anyone who thinks it might be jolly to take one of Bruges’s characteristic horse carriages between venues might be better advised to take a tumbrel.

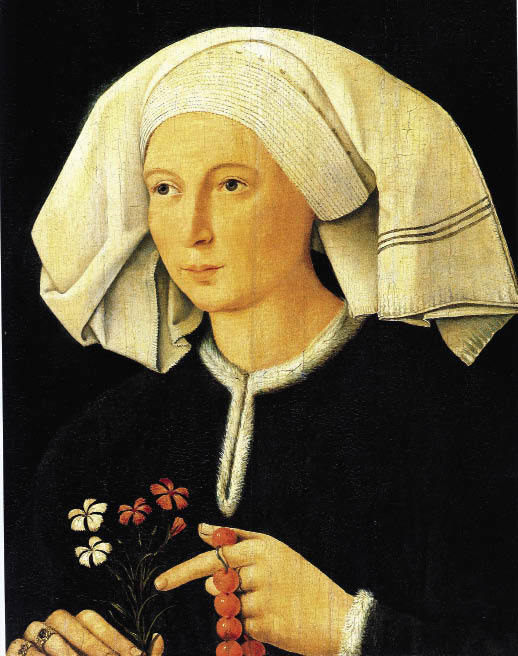

With nearly 300 exhibits, Van Eyck to Dürer also requires stamina, but little energy is wasted on written commentary (sensibly saved for the 550-page catalogue). Put crudely, the exhibition’s argument is simple: Flemish influence flowed irresistibly eastward until the prints of Schongauer and Dürer started a flow in the other direction. But of course things were more complicated than that. Martin Schongauer was influenced by Rogier van der Weyden and Dürer travelled in the Netherlands, though the 1521 journey commemorated here was more of a lap of honour than a pilgrimage, ashis fame preceded him. In the show’s last room, with its four Dürer paintings,we see why.

But even Dürer stole the landscapes in his prints from the Flemish, and in his paintings he never surpassed the realism of their detail. The show is stuffed with staggering examples, from the pile on the carpet at the feet of Van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele’ to the shine on the proto-cubist coffee pot behind Robert Campin’s ‘St Barbara’. A competition for painting fur is narrowly won, in the final room, by Dürer’s ‘Portrait of a Man’ (1521) over Quinten Metsys’s ‘Peter Gillis’ (c.1520). But with the exceptions of Schongauer, Dürer and the Bruges-based Hans Memling, most of the non-Netherlanders struggle with pictorial realism, shoehorning their Madonnas into wedge-shaped interiors and clothing them in drapery with folds like paper. The sort of realism that comes naturally to them is not an advantage: their babies tend to be fatter, their Virgins coarser and their martyrdoms more brutal.

The connections made by this show will fascinate scholars, but there’s a danger, for the inattentive visitor, of masterpieces being lost in the mix. On my first visit, I walked straight past Van Eyck’s exquisite drawing of a seated ‘Saint Barbara’ (1437) patiently waiting for her church to be built. Other highlights I would have kicked myself for missing were Van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele’, with its touching image of the overawed donor fumbling with hankie, prayer book and spectacles in the holy presence; Hugo van der Goes’s ‘Death of the Virgin’, with its psychologically complex group portrait of 12 grown men on the brink of crying; and Dürer’s ‘Saint Jerome’, with its unorthodox view of the usually ascetic Doctor of the Church as a rugged outdoor type with a deep tan and the sort of clunking fists you could imagine grasping a lion’s paw.

In pictorial terms, this is reality of the highest rank. Luc Tuymans’s terms of reference are more contemporary: he looks for realism in gritty subject matter. The Reality of the Lowest Rank, by definition, has no highlights, but I was moved by the Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow’s 1972 Herbier series of polyester moulds of her son’s body, opened out and stretched on to board like flayed skin. On the other hand, the blunt symbolism of Polish painter Andrzej Wróblewski’s painting ‘Mother with killed son’ (1949) — the son is painted blue and has a real bullet hole through his heart — left me cold. One lesson learnt from these two very different exhibitions is that realism can heighten emotional impact — but only realism of the highest rank.

Comments