One thing is certain: George W. Bush was no Pericles. For which reason it is a pity that John Hale’s new history of Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BC is launched with a rhetoric more Texan than Attic.

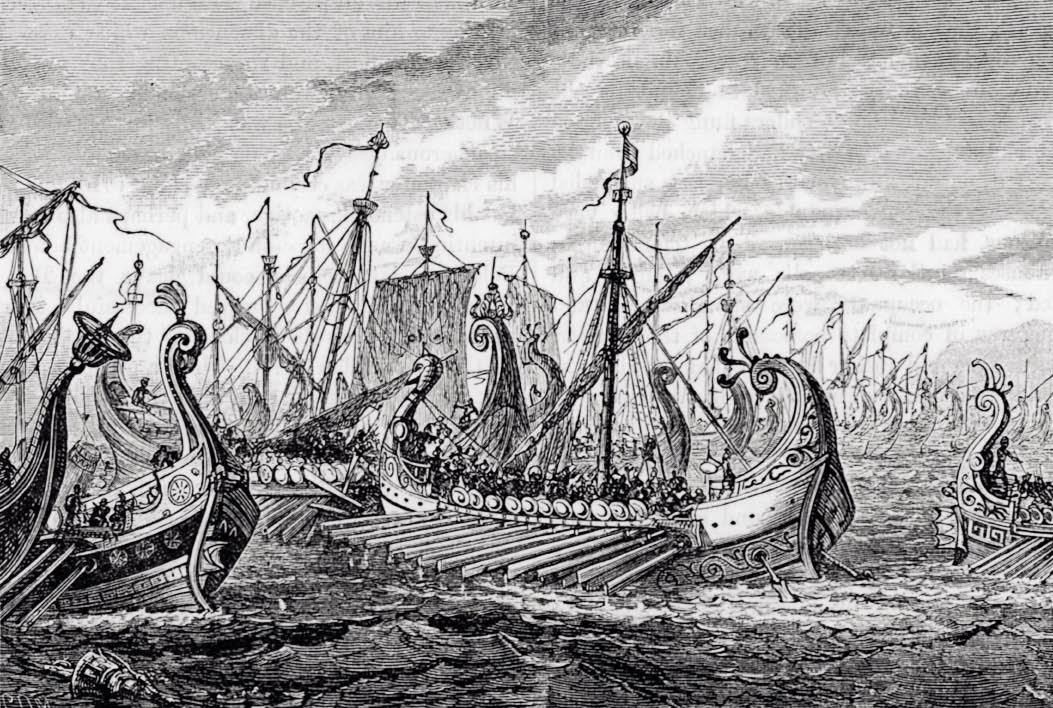

The ancient Greeks knew that building a navy was an undertaking with clear-cut political consequences. A naval tradition that depended on the muscles and sweat of the masses led inevitably to democracy: from sea power to democratic power. Athens was exhibit A in this argument, and radical democracy would indeed be the Athenian navy’s greatest legacy.

To be sure it was not Dubya — nor even Hale, a classical marine archaeologist from the University of Louisville, Kentucky — who called Athens ‘a democracy based on triremes’ and who argued that

Athenian democracy was strengthened by the masses who served in the navy and who won the victory at Salamis, because the leadership that Athens then gained rested on sea power.

That was Aristotle.

But it is one thing to acknowledge the profound democratising impact of almost universal military service — as, for example, in the second world war in Britain and elsewhere, though not the Soviet Empire — and quite another to detect an ‘inevitable’ causal link from sea power to democracy. On the face of it the requirements of good order and naval discipline, necessary as they may be for sea-going proficiency, are hardly redolent of the democratic spirit, however much English-speaking — or indeed Greek-speaking — romantics may cherish the dream that the special place which democracy has in at least parts of our history must somehow be connected with our love affair with the sea.

Were Parliament’s 17th-century victories over autocratic kingship or the revolt of the American colonies or the French Revolution or the 1832 Great Reform Bill in Britain, or indeed its successors in 1867 and 1884 , essentially driven by the experience of sea power? Cromwell, Marlborough, William of Orange and George Washington were soldiers; and Nelson’s crews did not become conspicuously active Chartists.

Ancient Athens was already to a degree democratic — more than 20,000 citizens could vote in the Assembly out of a total population in Attica of about a quarter of million — when in 483 BC Themistocles persuaded his countrymen to devote their new-found wealth from the Laurium silver mines to building a navy. His arguments were essentially those of Theodore Roosevelt and Admiral Alfred Mahan 24 centuries later: namely that sea-power was the key to trade, prosperity and political empire.

Promoting, let alone exporting, democracy was not mentioned. Punishing neighbouring Aegina for its repeated affronts to Athenian trading interests and security certainly was. It was a consequence of Athens’s incipient democratic tendency, not a cause of it, that the construction of the navy was to be based on a kind of private finance initiative whereby the state would lend silver to the richest 100 individual citizens to build and equip a warship.

To crew 100 new triremes needed 17,000 oarsmen, who could only be conscripted from the citizens whose votes in the assembly would decide whether Themistocles’s plan would be adopted. It was; but it was the democracy (at least of the minority who were citizens) that came first, not the navy or the sea-power, although power was greatly shifted away from the few and towards the many under the leadership of Pericles, another conspicuous protagonist of sea-power, and Ephialtes 20 years after Themistocles’s naval initiative.

Navies have been built and sea power developed in other climes and times without any general tendency to promote or export democracy. The Red Navy was, after all, at least the second largest the world has ever seen. The very Anglo-Saxon conceit that sea-power and democracy are somehow symbiotic is, alas, entirely fanciful.

This flaw should not, however, be allowed entirely to obscure other merits of Hale’s book. It is thoroughly readable and tells the naval and to some extent the political history of classical Athens from the early struggles against the Persian kings to the later wars with the Macedonian kings in an accessible and straightforward way. This is not by any token academic history; but it is a good story well communicated, even if one gags on the Dubya gracenotes. q

Comments