The history of the male ballet dancer is a chequered one. In the early 19th century, he was the star of the show, albeit more as an acrobat and tumbler than fairy-tale prince. The vogue for sylph-like damsels floating in white tulle put paid to that, reducing him to the auxiliary role of porter and attendant. Then came the comet of Nijinsky, introducing a note of mysterious Slavic androgyny that left the male dancer suspiciously homosexual and prone to the ‘pink tights’ cliché. Nureyev and Baryshnikov cemented the exotic Russian connection, until the late 1990s when the allure of the musical Billy Elliot and Matthew Bourne’s version of Swan Lake opened ballet up to a generation of British boys who would otherwise have preferred kicking a football around.

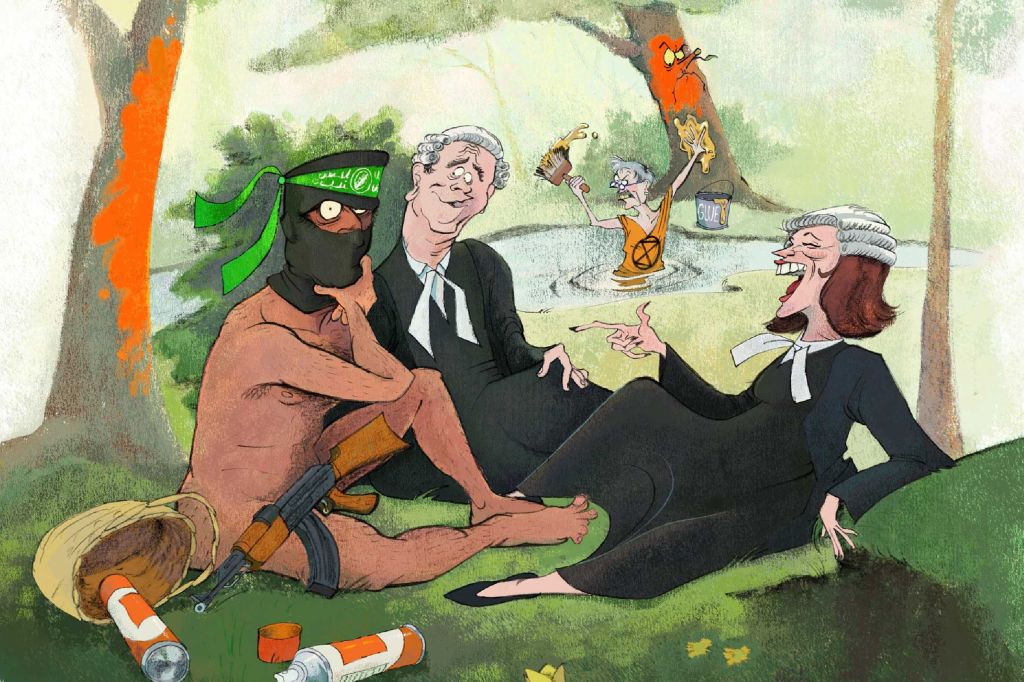

On the crest of this wave, William Trevitt and Michael Nunn abandoned their meteoric careers with the Royal Ballet to form BalletBoyz, an all-male company that has continued to thrive and expand: next year it celebrates its 25th anniversary. It drew its members from everywhere: Matt Rees, for instance, was about to join the Marine Commandos when he decided he’d rather dance – now he’s retired and works as a roofer. BalletBoyz has just put out a call for four vacancies; 250 applicants have responded. ‘Things are much easier for men who want to dance now,’ Nunn believes. But it disturbs him that they all seem obsessed with buffing up their bodies. ‘Great dancers of the past like Baryshnikov never went to the gym,’ he adds. ‘Now they spend more time there than they do in ballet class. Frankly, I’m more interested in how they dance than the weights they can lift.’

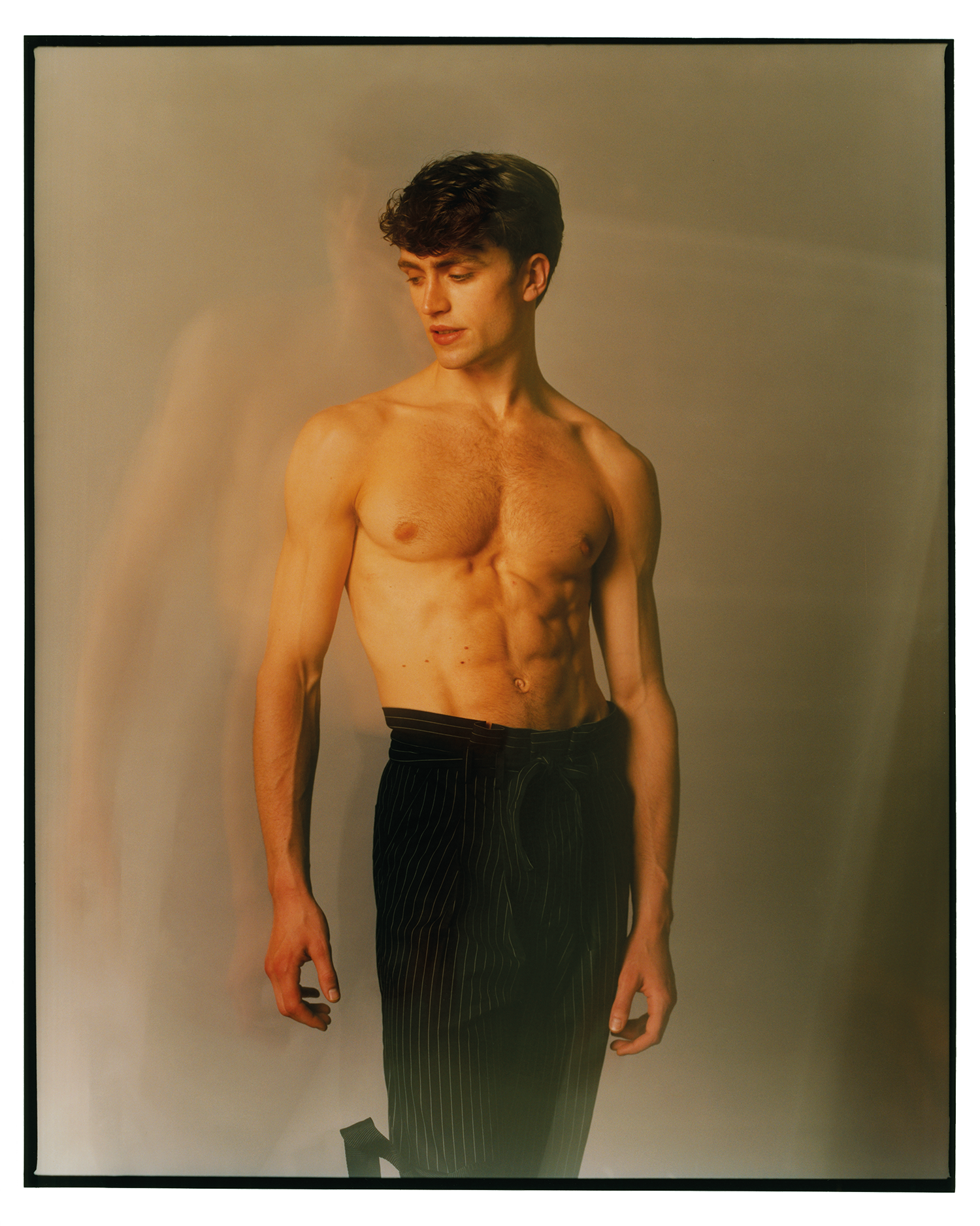

But the net result is the strongest cohort of male dancers that ballet in Britain has ever known. Among them Matthew Ball stands out. Born in Liverpool to parents who were dance and drama teachers, he was bewitched by Bourne’s Swan Lake and ‘totally obsessed with ballet by the time I was ten’. Now 31, he is in his prime, distinguished among his peers by more than a vivid stage personality, technical security and gym-fit physique; he is also a deeply thinking dancer, highly articulate and sensitive to the stylistic implications of whatever he is performing, whether it is a torrid melodrama such as Mayerling or a comic fantasy like Don Quixote.

Eight years at the Royal Ballet School provided him with a training about which he has mixed feelings. ‘I always felt that it was the right place for me, and it gave me what I needed in terms of the formalities of dancing,’ he says. ‘But you have to tow the line and you aren’t encouraged to ask questions in the way that actors would be asked to investigate their characters. What I missed, looking back, was a broader perspective or consideration of dance as a means of suggesting emotional expression. When I arrived in the company and started playing actual roles, it felt quite new and shocking to discover that you could use steps to tell a story.’ He passed an English literature A-level, as well as dance qualifications, but has he come out feeling under-educated? ‘The richness of experience I’ve had as a result of being at the school means that I can’t feel short-changed.’

His own professional career got off to what he describes as ‘a bad start’. Since the age of 14, his knee had been giving him gyp and five years on, at the same time as he had graduated into the company, he was sternly told that to give himself the best chance he shouldn’t postpone surgery. A failed operation would have spelt the end of his hopes. ‘My job was in jeopardy until I was healthy again, but I wasn’t on the payroll. I stayed on at the school for rehab, but they didn’t provide me with accommodation. It was a horrible nine months, and I was on the edge.’

Ball is a deeply thinking dancer, sensitive to the stylistic implications of whatever he is performing

Fortunately, the surgery worked and Ball began the ritual ascent up the militaristic hierarchy of ranks typical of ballet companies. ‘Some might say that the system is antiquated, but so is ballet, and it works. There were moments when I was halfway up when it seemed difficult to push higher, but I made it to the top rank in six years – I was a confident partner and that helped me. I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I wasn’t surprised when I was promoted to a principal – I had done enough major roles to make it seem a natural progression.’

In Russia, every dancer in a ballet company is assigned a senior figure who remains permanently their exclusive coach, guardian and confessor. Would such a mentor have helped Ball’s artistic development? ‘It would depend on who you got, of course. But I remember as a teenager wishing that I had a teacher like Alexander Pushkin who would invite Nureyev and Baryshnikov to dinners in his flat, read them poetry and talk about art. At the Royal Ballet School, it was just left up to you if you wanted to go to the National Gallery.’

What Ball has undoubtedly benefitted from is the liberal regime of Kevin O’Hare, the Royal Ballet’s director since 2012. ‘Kevin is very open to us exploring outside opportunities, and I’ve never felt hemmed in,’ he says. He has certainly taken advantage of this latitude. As well as dancing ballet as a guest in Hong Kong, Italy and Brazil, he’s recently been given leave to appear in (among much else) Deborah Warner’s season at the Theatre Royal Bath; a revival of Bourne’s Swan Lake; a ghastly rock ballet based on the Who’s Quadrophenia and an excellent online pay-to-view series on the art of partnering, which he hosts alongside his girlfriend and fellow Royal Ballet principal Mayara Magri. Modelling clothes – he was the face and body of Marks & Spencer’s autumn menswear campaign a few years back – is something he doesn’t take that seriously, ‘but it’s good for the bank account’.

He has firm views as to what ballet needs if it is to be taken more seriously as an art form. Although he appreciates the breadth of the Royal Ballet’s repertory, he wishes that more attention was paid to European choreographers such as John Neumeier and Jiri Kylian. Thematic programming, with informal introductory lectures would, he believes, ‘help audiences to more detailed and nuanced understanding’. He supports ballet’s current leanings towards narrative, and would like to see less ‘dance for dance’s sake. It’s hard to believe in the times we live that people have the urge to create without having anything to say.’

Did he ever suffer from the idiotic stigma around boys in tights? ‘Only from people who’ve never been properly exposed to ballet. I would love to challenge them to come and watch us at work and realise that it isn’t just vanity and prancing around or whatever. The interplay between artistry and athleticism has been the keystone of my inspiration and I can only feel sorry for people who can’t appreciate that.’

With ten to 15 years more on stage (if he’s lucky), he’s also cautiously begun to work as a choreographer and he’s not uninterested in the prospect of straight acting (a path followed by his precursors Robert Helpmann and Christopher Gable). Meanwhile, at home in north London, Magri is teaching him Portuguese and the cookery of her native Brazil – the idea that dancers live anorexically on coffee and cigarettes is another canard that needs binning. Next month, alongside an appearance in that seasonal balletic necessity The Nutcracker, he will give a lecture recital at the Royal Academy of Music, and you can be sure what he says will be as interesting as what he dances.

Matthew Ball dances in The Nutcracker at the Royal Opera House on 29 November and 8 December. On 14 December he gives a lecture recital at the Royal Academy of Music.

Comments