Kim Philby once remarked to the journalist Murray Sayle that ‘to betray, you must first belong. I never belonged’. Kim, as usual, was lying. Westminster and Cambridge, the Foreign Office and SIS: for all his attempts to pose as an outsider, Philby was a thorough-paced member of the British Establishment. George Blake — who is quoted using exactly the same phrase about himself in Simon Kuper’s wise, engaging biography The Happy Traitor — was telling the truth. Blake never belonged to a country, and communism was probably the closest thing he ever found to a spiritual home — even if he was deeply disillusioned by the reality of the workers’ paradise when his espionage career ended in exile in Moscow.

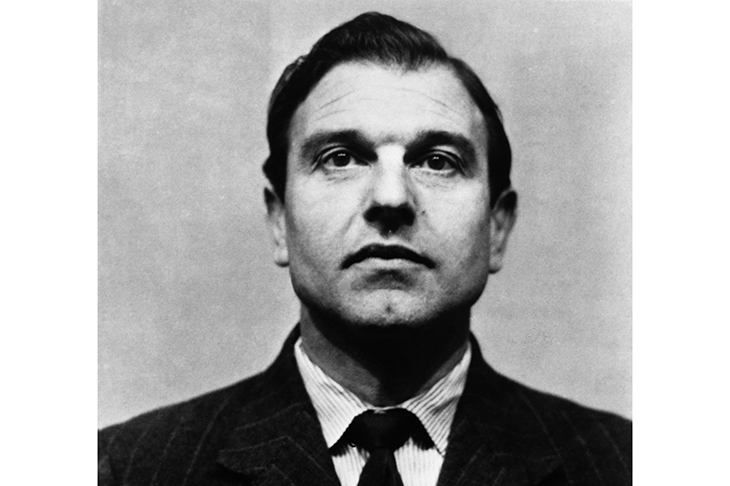

He was born George Behar in Rotterdam to a Jewish father and a strictly Protestant Dutch mother. His father, Albert, originally from Constantinople, had acquired a British passport after service with the British Army on the Western Front and named his only son after the King. Aged 13, George discovered his father’s religion only after his death. He was then sent to live for a spell with wealthy relatives in Cairo — who included the charismatic future communist, anti-colonial activist Raoul Curiel.

Blake came early to clandestine life. The outbreak of the second world war caught him back in the Netherlands. At 17, he began carrying messages across Holland for the Dutch Resistance on his bicycle. When life became too dangerous he staged a spectacular escape — his first, but by no means last — across Occupied France and Spain to England, where he volunteered for the Royal Navy. Headhunted by the nascent MI6 for his polyglot skills and proven anti-Nazi pluck, he was sent first to Cambridge to study Russian and then to Korea. Again war caught him out, and he and a handful of unlucky Brits endured a hellish two-year internment.

The Soviet embassy thoughtfully provided the foreign prisoners with tomes by Lenin and Marx, which Blake devoured. The terrible American bombing of Pyongyang reminded Blake of the Luftwaffe’s destruction of his home town a decade earlier. Blake told Kuper, in their native Dutch, during a rare three-hour interview in Moscow in 2012:

We, as representatives of the West, felt guilty and asked ourselves: ‘What are we doing here, what right do we have to come here and destroy everything?’ These people, who live so far from us, should decide for themselves how to organise their lives.

Blake’s espionage career didn’t make much difference – except to the lives of the men he betrayed

Blake returned to England a convinced communist. In many ways he had replaced the Protestantism of his youth with another, more vibrant faith. ‘I had become profoundly aware of the frailty of human life and I had reflected much on what I had done with my life up to that point,’ he told Kuper in the garden of a suburban Moscow dacha provided for him by the Russian state. ‘I decided to devote the rest of my life to what I considered a worthwhile cause.’ In the parlance of the trade, he became a ‘walk-in’, volunteering his services as a spy for the USSR.

Blake’s most notorious betrayal was of the Berlin Tunnel, a technically daring British-conceived and American-funded scheme to tap into the underground telephone lines which connected the Soviet military headquarters in Berlin to Moscow. The project was blown even before it was built — but the KGB held off for nine months after its completion before busting it. Kuper reveals that, amazingly, not only did the KGB not use their knowledge to pass disinformation to the West but they didn’t actually inform the Red Army that their communications were being intercepted. A desire to protect their source in SIS could have been behind this bizarre silence — but more likely, speculates Kuper, it was simply institutional rivalry.

In any case the voluminous transcripts yielded nothing of much use to the Americans, its prodigious banality confirming at least that the Soviets were not planning any kind of invasion of West Berlin. Refreshingly for a writer on espionage, Kuper resists the temptation to big up his subject, and freely admits that in the grand scheme of things Blake’s espionage career didn’t make much difference — except to the lives of the men he betrayed. ‘Spying in the Cold War wasn’t primarily a means of uncovering vital information,’ notes Kuper. ‘Rather, it was an internal game between western and eastern spy services.’

More controversially, Blake also gave up the names of hundreds of agents recruited by SIS in Eastern Europe. All were arrested and at least some — it’s not clear exactly how many — were shot. Questioned closely by Kuper, Blake dismissed his victims as casualties of war. ‘For him, betrayal was part of the spying game,’ writes Kuper:

After all, spying on one’s own country was fairly routine in his business. For much of Blake’s time at SIS, he was tasked with persuading Soviets and East Germans to work against their states. ‘This was my life work and it is bound to affect the way one looks upon betrayal,’ he said.

Intriguingly, Kuper frequently compares Blake and his fellow ideological spies to modern youths attracted to radical Islam:

Like many of today’s European jihadis, Blake was a pious young traitor, revolted by western excess (including his own). Like them, he was renouncing a libertine life of ‘pleasure’ in order to embrace a cause greater than himself.

And, as for jihadis, the deaths of enemy soldiers were simply an inevitable part of combat.

In 1961, a Polish defector revealed the existence of a mole in SIS. Blake fell under suspicion and was identified by a process of elimination — an investigation that gave another young SIS officer, John le Carré, his inspiration for the great fictitious mole hunt in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Blake confessed fully — largely, it seems, because he felt that his motives were honourable. But his cooperation did not stop the Lord Chief Justice from handing down a 42-year sentence. Other far more serious traitors such as Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross were let off scot-free. That was a sign, Blake believed, of the Establishment looking after its own while throwing the book at the treacherous foreigner — though he retained a lifelong admiration for Britain.

After five years in Wormwood Scrubs — where he became something of a hero to fellow inmates for his courtesy and foreign language lessons — Blake arranged a daring escape with the help of a former cell mate, abetted by several anti-nuclear activists. Hidden under the seat of a brave peacenik family’s camper van, he made it to Berlin, where he announced himself to a startled East German border guard. A comfortable retirement in Moscow followed, complete with an apartment, dacha, promotion to colonel, the Order of Lenin — and a new Russian wife. Philby and Donald Maclean were his friends, though perhaps his background as an eternal foreigner helped Blake adapt better to Soviet life than his homesick English colleagues.

Just one small error in this deeply researched book to be corrected. Blake’s codename ‘Diomid’ doesn’t mean ‘Diamond’ but is the Russian version of the Greek name Diomedes, as well as the name of a bay near his recruiter’s native Vladivostok. Blake died on Boxing Day last year, making this book uncannily timely. Kuper’s highly readable and multi-layered portrait is largely sympathetic, yet clear-eyed about the human cost of moral stances. Like the naive believer Alden Pyle in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, Blake’s attempt to save humanity ended up destroying lives.

Comments