Remember day trading, the fad for retail investors trying to emulate the hotshots of Wall Street from their spare bedrooms, and losing much of their money in the process? It is back with a vengeance, this time driven by a range of ‘disruptor’ apps which seek to lure risk-hungry traders by eliminating the cost of buying and selling assets. This time, the bets are even bigger. Controversially, some apps offer traders the chance to ‘leverage’ their bets: that is to borrow money to increase their gains. Or losses.

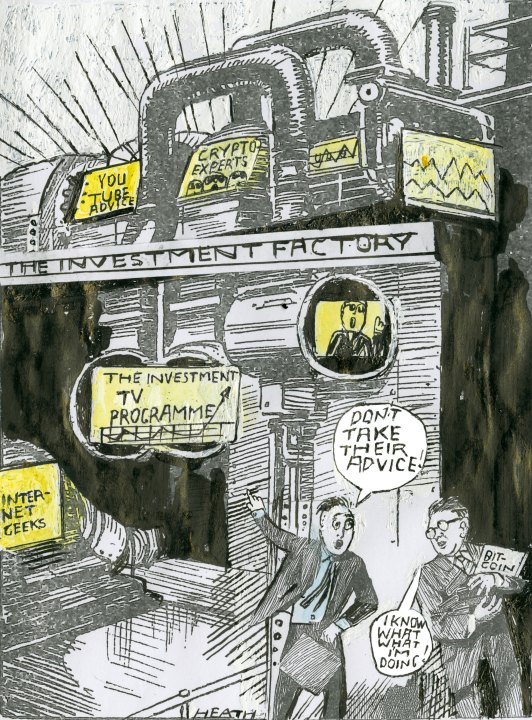

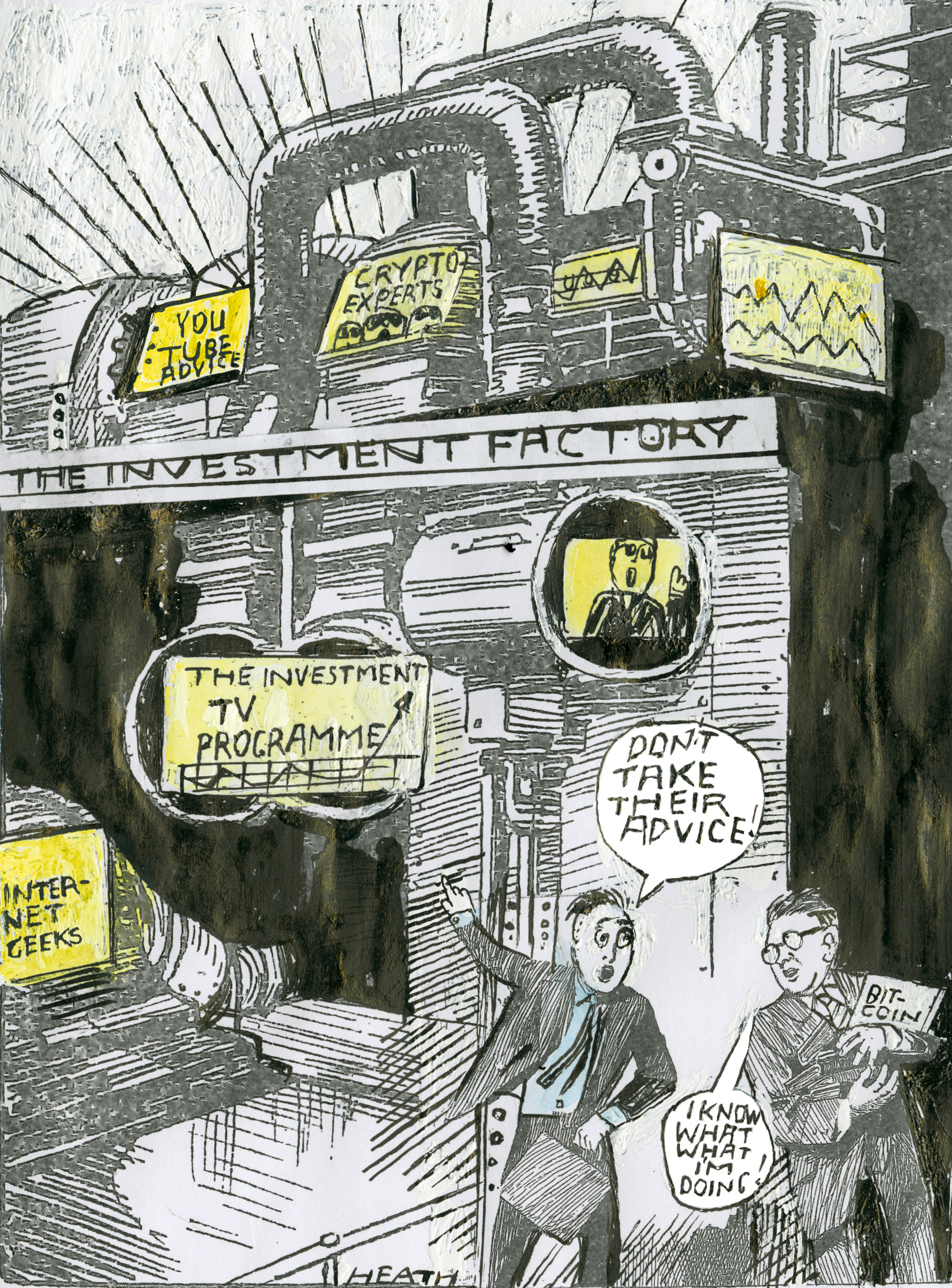

The story of canny investors looking to outsmart the system — and the charismatic ‘experts’ that lead them — is as old as the market itself. Yet with social media and the rise of influencers, the market for alternative investment strategies (or, as some see them, get-rich-quick schemes) has grown bigger than ever. Much of it is driven by a wave of younger, inexperienced investors who are prepared to take investment advice from unqualified strangers on the internet.

It’s a world shaped by the Bitcoin boom of 2017, when hundreds of thousands of investors sought the wisdom of self-styled crypto-experts on YouTube and internet forums. These analysts rarely had any discernible qualification, but wasn’t that the point? After all, if Bitcoin had been birthed by anonymous internet geeks in the first place, weren’t they the best ones to understand its future moves? The ‘experts’ were bullish: American investors on the other hand lost $1.6 billion on Bitcoin in 2018.

Traders have begun using TikTok, the video platform with a teenage user base

Cryptocurrencies haven’t gone away, but the search for instant riches has broadened into other assets. Visitors to YouTube are currently being targeted by ads for eToro, a Cyprus-based investment platform that has pioneered ‘social trading’ — a high stakes blend of traditional fund management and social media. Users deposit their money on to the platform and then effectively outsource their decisions to other, more influential traders — many of whom are in their 20s and 30s — by opting to ‘copy’ their investment strategy (an automatic process) with some or all of their pot.

Do the wannabe Warren Buffetts cut the mustard? It’s easy enough to check. eToro is transparent about traders’ track records, displaying data on their performance in the same way that conventional fund managers do. Given the money involved (many amateur traders are backed by millions of pounds of users’ cash, drawn from thousands of small investors) that seems a sensible move. Yet the social trading model, which relies on traders doing their own PR via social media, is subject to hype.

While traders are unlikely to engage in outright dishonesty (their claims can easily be cross-referenced against eToro) there is still some leeway for exaggerated claims. One common trick is to talk about impressive monthly gains (sometimes more than 20 per cent) when, as any seasoned investor knows, rapid gains are usually balanced out by losses in other weeks. Traders are smart, too, when it comes to reaching new audiences. Some have begun using TikTok — the immensely popular video-sharing platform with a predominantly teenage user base.

eToro is upfront that the social trading model is inherently risky: its website currently states that 66 per cent of users lose money when investing in contracts for differences (CFDs) — a complex model which seeks to take advantage of minor fluctuations in the price of assets. Unsurprisingly, eToro has attracted periodic attention from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), which in 2014 rejected the platform’s claim that it was operating as an execution only (i.e. non-advisory) trading platform rather than a traditional portfolio manager. The FCA is now reportedly considering tougher restrictions on marketing CFDs to non-sophisticated investors.

Needless to say, trading apps attract a disproportionate share of younger investors. Under-35s currently make up 33 per cent of eToro’s customer base and hold 55 per cent and 62 per cent of its stocks and cryptos respectively. The average user of Stake — an app which allows users to trade without paying transaction fees — is 32 years old. Its founder, Matt Leibowitz, believes that millennials are drawn to its simplified, and cheaper, trading model — made possible, he says, by changes in technology that make it cheaper to run a trading platform.

While social media has made it possible for unknowns to build big followings, it’s also supercharged the level of communication between investors. Personal finance is a perennially popular topic on Reddit, the internet forum frequented by a 330 million-strong base of predominantly male users. On the discussion board WallStreetBets users brag about their investment wins. Their current pick is Richard Branson’s much-mocked space venture Virgin Galactic (SPCE). Their interest in Branson’s venture was picked up by the Bloomberg business channel.

Is that why SPCE’s shares have suddenly jumped in value? WallStreetBets users like to think so. ‘My dad just called me about SPCE,’ one posted triumphantly, to the delight of the regulars. ‘He’s confused as to how a company that doesn’t do shit made $4 [per share] today. You guys are making boomers take notice.’

Is this new wave of risk-hungry trading just hot air driven by investors’ naivety? Google and Facebook both have their concerns, taking action against content aimed at amateur investors which they believe to be irresponsible or misleading. Some investment videos have been taken down from Google-owned YouTube. But while that might suggest they’re worried about legal ramifications, it also reveals something else: that the investment influencers must at least be getting through to somebody. For better or worse.

Comments