Bunnies were out. Beatrix Potter had the monopoly on rabbits, kittens, ducks and Mrs Tittlemouses. ‘I knew I had to bring in creatures of some kind,’ wrote Roald Dahl on his first thoughts towards a children’s book. ‘But I didn’t want to use all the old favourites that had been used so often before, like bunnies and squirrels and hedgehogs. I wanted new creatures that no one else had ever used.’ After making a long list of earwigs, pond skaters and Devil’s coach-horse beetles, Dahl cast a centipede, an earthworm, a silkworm, a glow-worm, a spider, a ladybird and an old-green-grasshopper. ‘It was fun,’ the author wrote, ‘to sit down and try to make a slimy old earthworm, for instance, into a rather loveable interesting character.’

Fun to draw, too. The illustrator chosen for James and the Giant Peach (1961), Dahl’s first book for children, was the American artist Nancy Ekholm Burkert, now 86. She got the gig with a ‘test insect’: a sketch of a grasshopper taking off in an aviator jacket and flying goggles. In the second world war, Dahl had been an RAF pilot. He wrote about the crash on his maiden flight in ‘Shot Down Over Libya’. (‘Lost Bearings Over Libya’ was more like it, but never let the truth get in the way of a good short story.) Dahl’s first serious success, The Gremlins (1943), had imagined the bogys that sabotage pilots and planes. Sitting in the chair of his writer’s hut at the bottom of the garden with a board across his lap was, said Dahl, like being in a cockpit. The Dahlhopper is a highlight of an exhibition at the Roald Dahl Museum dedicated to Burkert’s magnificent illustrations for the first edition of James and the Giant Peach.

On 5 June 1957, Dahl’s agent Sheila Saint Lawrence had encouraged him to ‘get away from the short story formula which is imprisoning you at the moment, and to reindulge yourself in the realm of fantasy writing’. Dahl’s notebooks were filled with one-line ideas: ‘Turtle Boy’, ‘the cold-cure inventor (tiny insects in soil?)’, ‘the magic tape-recorder’, ‘the child who could move objects’, ‘tiny humans in hollow tree’. If no notebook came to hand, he would write a single word — ‘elevator’, perhaps — in the dust on his car. The scheme he fixed on may have been jotted down as early as the late 1940s: ‘the cherry that wouldn’t stop growing — fairy story?’ The cherry became a peach, chosen for its yielding flesh and sensuous fuzz.

We think of Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake going together, like, well, peaches and cream. But before there was Blake, whose first Dahl commission was The Enormous Crocodile (1978), there was Burkert, a former Girl Scout, born in Sterling, Colorado, in 1933 and brought up in Wisconsin. Her illustration heroes were all English: Arthur Rackham, E.H. Shepard, Beatrix Potter. After a fine art degree and masters at the University of Wisconsin, Nancy sent a manuscript in verse and five large original paintings ‘over the transom’ to the publisher Alfred Knopf in New York. It was Knopf editor Virginie Fowler who matched Dahl and Burkert. ‘I do think we have a gem in this artist,’ Fowler wrote to Dahl on 17 August 1960.

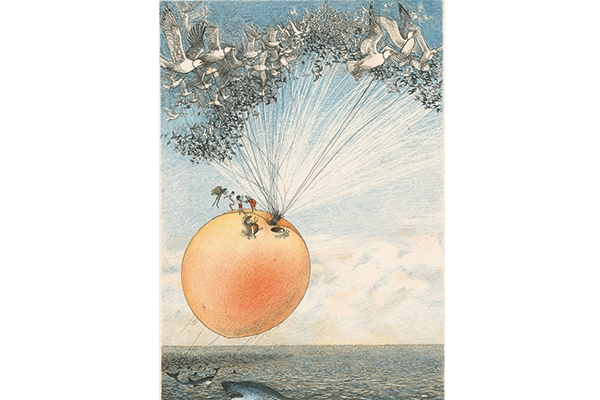

If Blake’s illustrations bring out the madcap in Dahl, Burkert’s are sheer, soaring magic. She understood Dahl as a spinner of tall tales and twisting fables. James, after all, is a story all about spinning. James saves the insects from certain death by circling sharks when he orders the spider and the silkworm to spin and spin until James has enough lassos to capture a flock of seagulls (poor, old earthworm is used as bait) to fly the peach to safety.

Burkert, answering questions by email, remembers Dahl as ‘kind and courtly’. She includes the author in the scene of James’s triumphant procession through New York with a pencil (Dahl always used Dixon Ticonderoga HB) behind his ear. Alfred Knopf, wearing a red-and-black striped cap, can be seen behind a ginger-beer stand.

Dahl told Virginie Fowler that A.A. Milne’s Christopher Robin, as drawn by E.H. Shepard, ‘is and always will be the perfect small boy… We should get closer to that… A face with character is not so important as a face with charm.’ James, in his too-short shirt and ragged sleeves, is affectingly scrawny. Burkert’s model was Toby, the young son of lithographer Harold Altman.

Burkert took care over every line. The flowers that grow in the garden of Aunts Spiker and Sponge are all English blooms, the insects are anatomically and entomologically exact down to the last antenna. She has the gift — as Potter had — of making animals both creaturely and human. When James first meets the insects inside the peach, the scene is somewhere between opium den and Oxford tutorial. The chairs are Chippendale, the rug an Aubusson. The centipede wears a boater, the earthworm a collar, tie and bowler hat. When James sets up home in Central Park, the peach stone becomes a New York brownstone with front steps and iron railings.

You need a magnifying glass to see every last shark, seagull and hair on Aunt Spiker’s chin. Burkert depended on Winsor & Newton watercolours and their finest brushes. At university she had studied Albrecht Dürer and the Flemish artists Rogier van der Weyden and Hugo van der Goes, but also the symbolist Odilon Redon. Later, her husband, the artist Robert Burkert, gave her a book of Japanese prints. All these influences come together in James: the miniaturism of the Flemings, the mayhem of Redon and the precision of line found in Japanese manga. Her rendering of the Cloud-Men who throw hailstones at the peach recalls the skyscapes of Chinese brush paintings.

For many years, Burkert worked at home, wherever she could make space. She would draw and paint ‘late into the night while my children were sleeping. No tea, coffee or scotch necessary, but a bourbon cocktail with my husband before dinner was a welcome ritual.’ Her favourite fruit, she says, disloyal for a moment to James, is the Santa Rosa plum.

Comments