Renard; Mavra; The Rake’s Progress

Glyndebourne

Anyone who was lucky enough to go to Glyndebourne on one of three days last week had the option of seeing not only the opera they had booked for, but also, before it, a couple of brief works by Stravinsky that were put on by the Jerwood Chorus Development Scheme, with the Britten Sinfonia and young singers, in the Jerwood Studio. It was rigged up as a circus tent, the action of the pieces taking place in the arena, while the small orchestra — a little too backward — played behind that. The two together made 45 minutes of bliss, Stravinsky at his insouciant best, though with imposing moments or more of ritual.

The works were sung in English translation, but the feeling of Russianness was very strong. There are passages that remind one of the great Symphonies of Wind Instruments, alternating solemn chordal passages with rapid edgy ones. The spirit in both is one of mischief, in Renard as one would expect; in Mavra, about a girl who gets her Hussar lover into the house disguised as a new maid, that spirit is even more pervasive, though the girl has a superbly erotic aria, and altogether Stravinsky lets his hair down more than he ever had before. What is odd, in the highly formalised treatment he gives to both these subjects, is how involving, indeed touching, they are.

That made them a stark and instructive contrast to the evening’s main meal, The Rake’s Progress. It also made them, for this longest of Stravinsky’s works, something to reflect on as the note-spinning longueurs of this final neoclassical piece played themselves out, in the slightly too loving and mellow reading of Vladimir Jurowski. For one of the very few times in his career, Stravinsky put, or attempted to put, flesh-and-blood human beings on the stage, singing, not dancing (in the two small works we get both). Auden and Kallman gave him an unsatisfactory libretto, though, to engage in this unfamiliar enterprise. For lovely though some of the lyrics are, and brilliant as the characterisation of Nick Shadow, the Devil, is, the text is so self-consciously clever, the tableaux so jerky in their progress, the motivations so contrived, that the Rake himself, above all, remains an ill-defined figure. Surely he should get some pleasure before slithering down the hedonist’s path to madness? And surely he might take some initiative rather than being the pawn of Nick from the outset?

Stravinsky, so far as I know, never expressed any reservations of this kind about the libretto in talking or writing about it, though he did voice others. But one might feel that he didn’t need to, because it is all too clear from the music he wrote that he was not creatively engaged, however he felt, until the last half-hour, when the opera suddenly moves into greatness and remains there until the extremely tiresome little Epilogue. The music, which seems unable to breathe life into Tom and Anne, let alone the motley collection they encounter in London, has nonetheless to come up with arias and ensembles; but Stravinsky’s melodic genius having temporarily dried up, none of them is in the least memorable. The soprano show-stopper (would be) ‘I go to him’ is merely animated, not even hinting at Anne’s anxiety. Because the librettists came up with nothing better than stereotypes, Stravinsky, who deals mainly in them, did the same, but the enterprise backfired. At least, that is the only way that I can account for the flatness that pervades the opera until the graveyard scene. There is no other work by anyone that I can think of where the level shifts so drastically, and so late: with the opening bars of that scene (the first to be composed) genius is apparent, and the tension of the card game — but why does Nick give his victim another chance? — is intolerable, Tom’s baroque anguish extraordinarily moving. And of course the final scene is on a level which ranks with Stravinsky’s supreme achievements, or may surpass them, being so different from any of the others.

The Glyndebourne production of John Cox, with David Hockney’s famous designs, shows not the slightest hint of aging. It is as fresh and as revelatory as it was when I first saw it in 1975; and a very strong argument against those people who tell us that productions must always be making the works produced new in some jolting way.

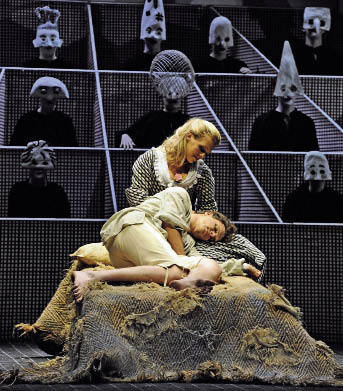

And the casting is virtually ideal, with the stupendously malevolent, terrifying Nick of Matthew Rose towering above all of them and all of us. This young artist is already great, and will be greater. The two lovers are, appropriately enough, ones we encountered in the sublime Così of 2006: Miah Persson the exquisitely beautiful Anne, singing with the purity of tone which the role demands; and Topi Lehtipuu wonderfully natural, eloquent as Tom, though his voice took quite a time to settle down, and won’t I think ever be a great one. Among the rest of the cast Graham Clark’s impatient, eloquently sung Sellem stood out. A great evening, only let down by the first three-quarters of the opera itself.

Comments