When Boris Johnson first became Prime Minister, he did not have a majority in parliament. Still, he didn’t worry too much about making friends with Tory MPs. He decided to work from the outside in, using his public popularity to pressure colleagues. A snap election was looming: backing him, he said, was their best hope of surviving. He was right, and delivered a majority of 80. This gave him huge personal authority. MPs deferred to his judgment even when they disagreed.

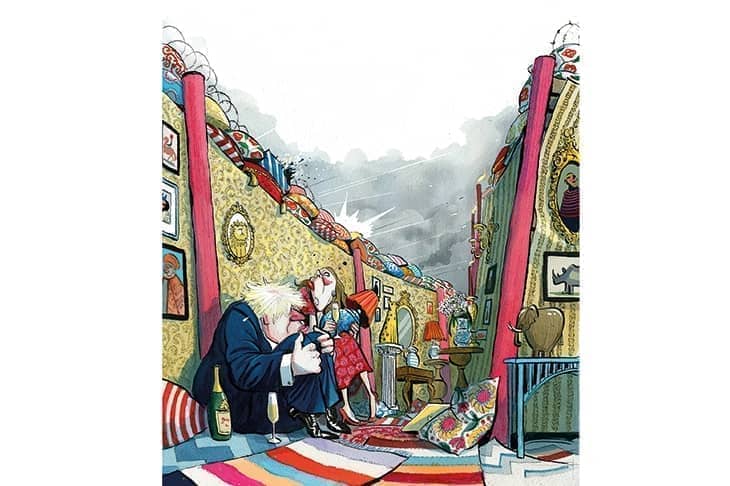

How different things look now. Johnson finds himself pleading with his MPs not to pull the plug on his premiership in what seems like a daily struggle. ‘He’s now a prisoner of the parliamentary party,’ says one minister. They make demands; he attempts to appease them. Everything — from staff changes at No. 10 to the makeup of the whips’ office — is designed to show that he is listening to backbenchers. We have entered a new phase of government where almost everything the Prime Minister does is aimed at placating his MPs. They, not the public, are the audience he is most concerned about for now.

The lockdowns, the Owen Paterson debacle, ‘partygate’ and dismal parliamentary management have all taken their toll. Only a few months ago, those close to Johnson spoke about a decade in power. Now, they’re hoping to make it past next week’s half-term holiday. One loyal cabinet minister hopes that if a challenge ‘doesn’t materialise before half-term, it won’t happen for a while’. Another government member points out that there are only seven weeks when parliament is sitting between now and the May elections (which will be his next major electoral test).

Johnson’s team desperately needs this break. The new No. 10 operation needs time to settle in and work out how (indeed, if) things can function. Johnson has committed to a restructuring of Downing Street and the creation of a new Office of the Prime Minister. But trying to set this up on the fly is not at all easy.

Johnson’s most ardent cabinet supporters are exhausted. The last few weeks have seen them encourage the PM to come out swinging and respond vigorously to his critics. But this had led to mistakes such as the Jimmy Savile barb. Even now, there is a failure to see that some subjects are not suitable as a basis for political attacks.

Johnson’s refusal to apologise over the Savile remark has already cost him Munira Mirza, his head of policy and one of his longest-standing and most trusted allies, who resigned in disgust. He cannot afford many more such errors. ‘There’s quite a lot of latent exasperation among colleagues. It won’t take much to tip things over the edge again,’ says one cabinet minister.

At the political cabinet this week, Johnson told his colleagues how voters hate to hear politicians talk about themselves. But his focus must be on his MPs right now. As the old Yes, Minister joke has it, the public can’t vote against you until the next election, but your MPs can vote against you this evening.

Hence this new, super-defensive mode of government where survival is seen as victory, and not upsetting Tory MPs is now a key governing objective. Johnson is sacrificing his own pet projects. His willingness to dilute his anti-obesity strategy is a sign of his diminished status. His aides spend their time poring over spreadsheets which contain demands from his MPs — for every-thing from policy changes to personal preferment. Even the debate about repealing the 1824 Vagrancy Act (which outlaws rough sleeping) is being shaped by the question of whether this would make MPs more or less likely to depose him. Cabinet reshuffles are meant to be about improving the delivery of public services. Now they’re being designed to reassure Tory MPs.

In this new, super-defensive mode of government, survival is seen as victory

Another sign of the weakness of the Prime Minister’s position is the fact that no one was sacked in this reshuffle: he could not afford to have anyone else outside the tent. The new appointments reflected the priorities of parliamentarians, not the public. The ministers whose job it is to keep Tory troops in line — the chief whip and the Leader of the House — were changed, while those dealing with matters that concern the public more were left in place. Anything to stop the 54 letters going in.

If the letters do go in, and a no-confidence ballot is triggered, it will be a disaster for Johnson. As Theresa May’s fate demonstrates, surviving this vote tends to be a pyrrhic victory. Even if you win, a large enough number of your MPs will have voted against you to leave you broken-backed. For Johnson the problem is particularly acute, as discontent with him isn’t concentrated in one faction but is spread across the entire party. The number of votes against him would exceed three figures and once that happens, it is very hard to keep going.

Officially, Tory rules keep leaders safe from further challenge for a year. Unofficially, the party can do what it wants. ‘If people felt their ability to express an opinion was being constrained by the rules, then they wouldn’t bat an eyelid about changing those rules,’ warns one secretary of state who knows the parliamentary party well.

Hiring Steve Barclay as chief of staff is yet another indication of how committed No. 10 is to keeping MPs happy. He has replaced Dan Rosenfield, a Treasury civil servant-turned-banker who had little understanding of the parliamentary party (he once surprised colleagues by asking them how Tory candidates got selected). Having an MP as chief of staff has — despite the operational challenges it brings — gone down well on the green benches. Barclay is the kind of calm, details-oriented, competent figure who fits the bill.

His appointment has also spared Johnson from having to find someone from outside. Finding an external chief of staff might have been a challenge, given the current state of the Johnson premiership, though some who are close to the PM think that they have a good chance of persuading Samantha Cohen, a former assistant private secretary to the Queen, to join the operation.

Johnson is famously slow to make new friends and has a habit of recycling old ones. Guto Harri, who worked with him when he was mayor of London, is now back as his communications chief. A surprise appointment, given that Harri and Johnson had been on opposing sides over Brexit. Yet Harri’s account of them singing Gloria Gaynor to each other reveals how comfortable the PM is with his old friend.

If Johnson makes it through the May local elections and their aftermath, governing will be harder — politically — than at any time in the pandemic. With a rock-bottom approval rating and a squeeze on living standards, Johnson must emerge from party-gate and build a recovery narrative.

The NHS backlog, always a concern, is fast turning into a disaster. Leaked figures revealed by Kate Andrews in her article show that the NHS England waiting list, six million now, is expected by the NHS to rise to 9.2 million by March 2024 (the most likely date of the new election). That’s despite the money from the coming tax rise. How can this be sold as progress?

Then there is the issue of illegal Channel crossings. Tory voters are hugely exercised about it — for them, immigration is in the top three issues facing the country — but the government still has no immediate answer to the problem. ‘We promised them a Brexit that would bring back control over borders,’ says one cabinet member. ‘Where’s the control?’ As Johnson has taken to lamenting, there is no easy fix, despite what the Tories have previously suggested.

If this government relaunch fails, then there’s always the possibility of another one. There is already talk of another reshuffle after the May elections: the hope is that the prospect of promotion will make would-be mutineers think twice. But a reshuffle in which people lose their jobs (as opposed to being moved around, as they were in this week’s safety-first exercise) brings dangers with it. ‘Reshuffles create more enemies than friends, and enemies are signatories for letters,’ warns one cabinet minister.

Surrounded by loyalists, in hock to his backbenchers — it should, in theory, be hard for Johnson to slip up. Hard, but not impossible. ‘Boris’s ability to dig fresh holes for himself once he’s cleared the old ones is pretty boundless,’ laments one friend. Yet his political situation is still better than many would have expected a week ago; the trickle of letters has still not turned into a flood. His team are increasingly confident of making it to the May elections without challenge. ‘MPs don’t want more bloodletting or another leadership contest,’ says a cabinet minister.

This is Johnson’s great protection: his party is not ready for a fight; and his enemies have let their hatred of him cloud their judgment. They have been so keen to hype up the police investigation into partygate that if no action is taken against him personally, he’ll be able to claim exoneration. His opponents also forget that Tory MPs believe it is Tories who should determine who leads their party. Interventions by external forces — whether it be the defection of Christian Wakeford to Labour or media pressure — tend to make them close ranks.

And might Johnson’s new strategy of hunkering down pay off? His backers claim that he specialises in resurrection, in defying all near-death experiences. Why, they ask, would the Tory party really want to jettison the best campaigner they have had since Thatcher? Against that we must set the lack of a clear agenda. A government needs to have higher ambitions than just keeping its own troops happy.

For now, the momentum that the rebels had at the end of last week has been halted, with most Tory MPs inclined to let the new set-up bed in while they wait for the Gray report. Johnson has again succeeded in buying himself some time.

Comments